Explore our Building and Collections

Our building was built for the Society to house our historically important Collections. It has beautiful architectural features designed to reflect and support the Society’s purpose for the study of natural history.

Visit the Society to see them for yourself - we are open Tuesday to Friday, 10am–5pm, or book onto our monthly treasures tours for an in-depth guided tour.

Melusines hold the main staircase lamps.

Leaves and flowers on Library Upper Gallery railing.

The Linnean Society’s initials on the Library ceiling.

Collections highlights

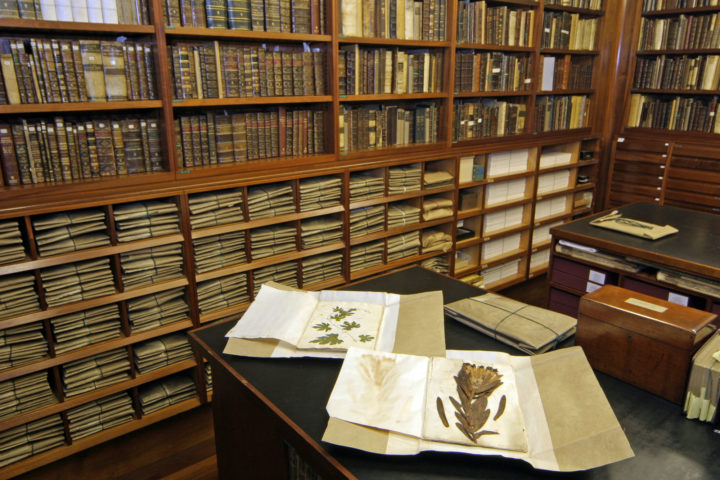

The entirety of the Linnean Society's library, archive, and biological specimen collections were recognised as a Designated Collection of outstanding national importance by Arts Council England in 2014.

Carl Linnaeus

The work of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) is of fundamental importance for the practice of biology today. Not only were Linnaeus’ classification systems influential (he was the first naturalist to put man in the animal kingdom, for instance), he was also the first naturalist to standardise the binomial nomenclature that is still used today (for example: Homo sapiens for humans, Canis lupus for the dog, Rosa canina for the dog rose).

"If you do not know the names of things, the knowledge of them is lost, too."

The Linnaean collections include biological specimens of crucial importance to the scientific disciplines of taxonomy, evolutionary biology, pharmaceuticals, and conservation. Linnaean collections and names underpin many aspects of human endeavour, particularly the global trade in plant and animal commodities. Many of these specimens are type specimens. These are specimens selected to serve as representative example of the species. Together with supporting information in books and manuscripts, they are of fundamental importance in understanding the diversity of life on our planet. Here are a few highlights:

The Linnaean Herbarium contains over 14,000 specimens, many pre-dating Linnaeus’s seminal work, Species Plantarum (1753). More than 4,000 specimens are type specimens for Linnaean names.

The herbarium includes plants from Asia, Europe and the Americas collected during a time of intense European exploration. The Society’s Linnaean herbarium is particularly rare because it is an example of a personal herbarium of a famous scientist that has been kept in its original state.

Listen to Curator of Botany Dr Mark Spencer talk about the Linnaean herbarium.

Below are examples of plants that were first named by Linnaeus and whose scientific names have not changed for the last 270 years:

- Plants loved by gardeners:

Common camellia: Camellia japonica

Dog rose: Rosa canina

Siberian larkspur: Delphinium grandiflorum

Fern leaf peony: Paeonia tenuifolia

- Crop plants, essential to world-wide agriculture and economy:

Rice: Oryza sativa

Maize, or corn: Zea mays

Potato: Solanum tuberosum

Grape: Vitis vinifera

Apple: Pyrus malus

- Medicinal plants:

Lavender: Lavandula sp.

Hemlock: Conium maculatum

Peppermint: Mentha piperita

The fish in Linnaeus’ collection are glued on paper (and no, they do not smell!). The collection holds 168 fish specimens consisting mostly of dried skins from one side, sometimes incorporating half of the skeleton.

There are a number of important type specimens in the collection, including the John Dory (Zeus faber).

Some are simply dried, like the seahorses. Linnaeus, who did not know that male seahorses carry their offspring, identified the smaller specimen with a pouch as a female. In fact, it is a male. Watch James MacLaine (NHM) uncover the mysteries of Linnaeus' seahorses to find out more.

The shells collection includes shells collected by Carl Linnaeus, both father and son, and James Edward Smith, founder of the Linnean Society.

The Paper nautilus shell (Argonauta argo) is extraordinarily fragile but has survived the centuries almost intact.

Linnaeus was the first to artificially produce pearlsfrom freshwater mussels in the river of his hometown Uppsala. He kept his methods secret. Watch the video on Linnaeus' pearls.

The Society holds ca. 9,000 insect specimens, including some 3,200 Linnaean ones, of which many are important types.

The insects collection includes beetles, butterflies and Hymenoptera (wasps, bees and ants). It also contains spiders and crustaceans (neither of which are insects!). Many of them still bear the names that Linnaeus gave them:

- Beetles include the impressive Hercules beetle,Scarabaeus hercules. Listen to Curator of Entomology Suzanne Ryder (NHM) talk about Linnaeus' Hercules beetle.

- Butterflies

TheAmerican Monarch (Papilio plexippus) is perhaps the best known butterfly in the world. The remarkable annual migration of almost countless millions of Monarchs from the Great Lakes to a narrow belt of mountains in central-southern Mexico have inspired wonder and awe. The Society holds the type specimen of the Monarch, as it was first officially named and described by Linnaeus.

This female specimen of an Old World swallowtail (Papilio Machaon) from Sweden is a type specimen. It even represents the whole genus of butterflies (Papilionoidea). This represents everything that a butterfly should look like!

The rest of the Linnaean collections includes the books from Linnaeus' library (including copies of his own works, annotated and corrected in his hand), his manuscripts, and the lettersthat he received from correspondents all over the world. They all inform and enhance the biological specimens.

- Linnaeus' most important publication is Systema naturae. Published in 12 editions in Linnaeus' lifetime, it aimed to classify and name the whole of the world’s minerals, plants and animals, and grew from three tables (1735) to three volumes (10th edition, 1758). Watch a video aboutSystema naturae and Linnaean classification.

- Linnaeus' most well known manuscript is his 1732 Lapland journal. It celebrates the healthy, nomadic life of the Sámi people, weaving together local knowledge and Linnaeus' observations on the local plants and animals with myths and legends from the region. Listen to Dr Staffan Müller-Wille (University of Cambridge), talk about Linnaeus' journey; read a blog describing a Library display on the Lapland journey.

- Linnaeus corresponded with more than 600 people across the globe. The Society holds more than 4,000 letters sent to Linnaeus. One of these was sent by the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Writing from Paris in September 1771, Rousseau wrote fan mail to Linnaeus, ending his letter with these passionate words: ‘I read you, I study you, I meditate upon you, I honour you and love you with all my heart.’

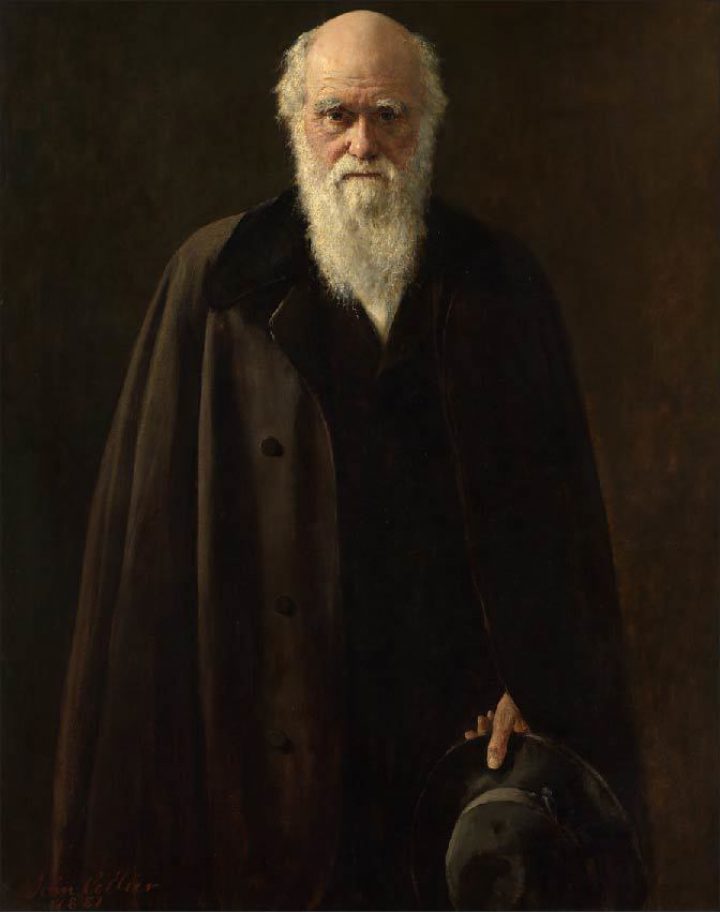

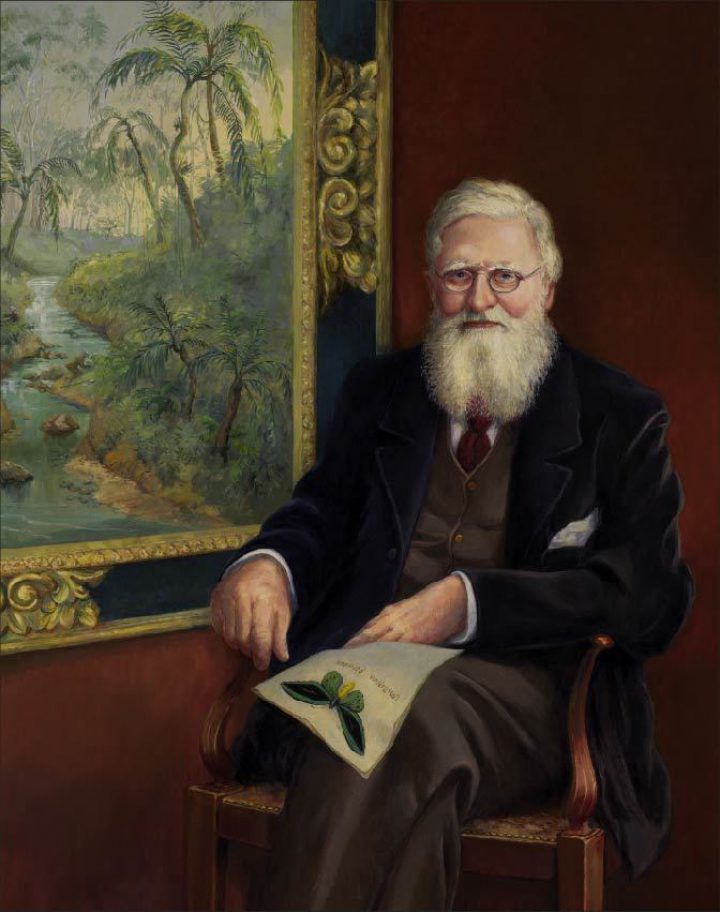

Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace

The Linnean Society holds striking items that relate to these two great naturalists, who changed the way we understand biology and our natural world.

- In 1831, Darwin embarked on the Beagle for an adventure that would change his life – and our understanding of life itself. With him he took a vasculum, a portable metal box, in which he carried the specimens he collected in the field. It is now on display at the Linnean Society. Watch a video to learn more about Darwin's vasculum.

- Alfred Russel Wallace arrived at the same theory of evolution by natural selection as Darwin, through his meticulous observations of the natural world, spending years in the Amazon and in the Malay Archipelago. The Society holds many of his manuscripts.

- Darwin and Wallace wrote a joint paper presenting their theory of evolution by natural selection. This paper was read in front of a small audience at a meeting of the Linnean Society on 1 July 1858, changing biological science and our understanding of the natural world forever.

- A year later, in 1859, Darwin published his Origin of Species. The Society holds a first edition, presented to the Society by the author.

- In 1881, the Society commissioned the famous portrait of Charles Darwin. Darwin was initially reluctant to sit for his portrait, writing to the Society ‘It tires me a great deal to sit to anyone, but I should be the most ungrateful and ungracious dog not to agree.’ According to Darwin’s third son Francis, Darwin and many of his acquaintances thought John Collier’s painting was the best of all Darwin’s portraits.

Manuscripts and artworks

The manuscripts and artworks are part of the Linnean Society’s archives. Many of them came from the Society’s Fellows, and date from the late 18th century to the present day.

- The Society Papers consist of manuscripts of papers that were read at meetings of the Society. They include papers by George Bentham (botanist, FRS and nephew of Jeremy Bentham), Robert Brown (discoverer of Brownian motion), Charles Darwin, the American botanist Asa Gray, and many others.

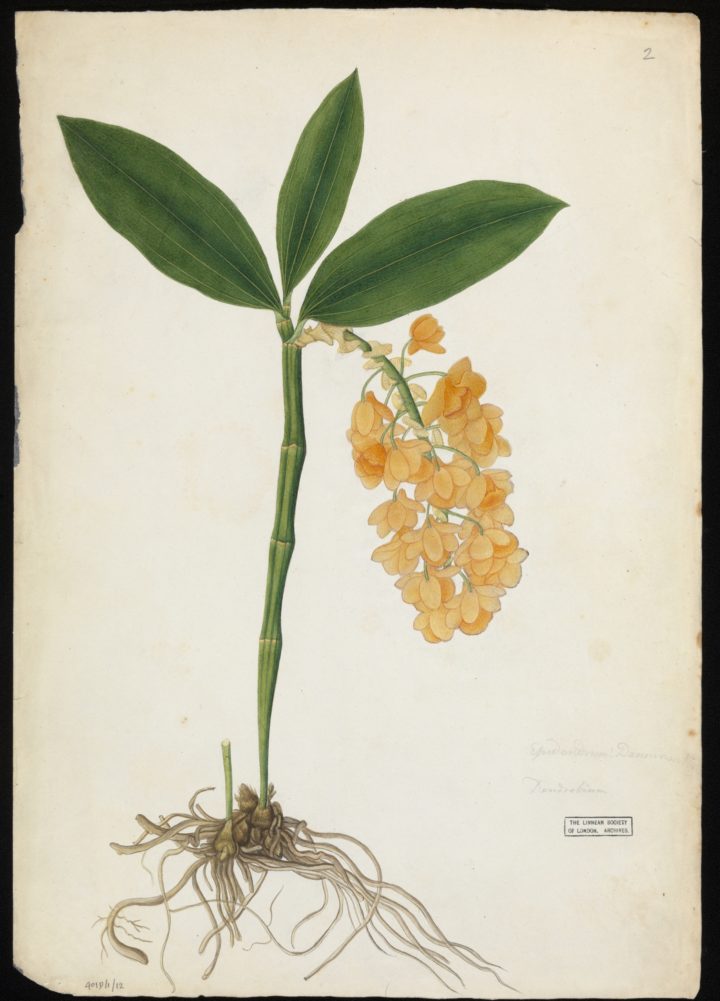

- Many Fellows of the Society worked as physicians or surgeons to the East India Company, or travelled to the West Indies and America. They employed local and indigenous people to help them locate and collect specimens, as well as artists who drew animals and plants for them, mixing local and European traditions and drawings techniques. Here are three examples from the early 1800s:

Francis Buchanan-Hamilton, a physician with the East India Company, travelled to Mysore, Bengal and Nepal. One of his most gifted artists was the Bengali Haludar. The Society holds their manuscripts, paintings and specimens.

Listen to how Dr Mark Watson (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh) makes use of this collection to inform his research.

(Left) An orchid collected in Nepal by Buchanan-Hamilton and probably drawn by Haludar.

Major-General Thomas Hardwicke travelled to India as a soldier and naturalist. He sent back many papers to be read at meetings of the Linnean Society, accompanied by stunning paintings. His description and painting (by an unknown artist) of a red panda (left) was probably the first one ever to reach Europe.

Alexander Anderson, second director of the Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Botanic Garden, employed several local artists to depict the garden's plants. One of these was a young black man by the name of John Tyley.

(Left) An avocado (Persea americana) drawn by Tyley for Anderson in Saint-Vincent.

- John Swainson's diary of his journey to the Lakes in 1799, although not illustrated, vividly recounts his trip and his impressions of the towns and landscapes he visited.

- James Edward Smith’s decision to purchase the Linnaean collections in 1784, and later establish the Linnean Society, catapulted him to the highest echelons of scientific and civil society. In 1792 he was invited to tutor Queen Charlotte and the princesses in botany and zoology, and Smith’s vast correspondence collection gives an insight into this brush with royalty.

Rare books

The English painter and poet Edward Lear, best known for nonsense verse (most famously the ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’, and his many limericks), began his career as a brilliant natural history illustrator. One of his most renowned publications was his beautiful monograph of illustrations of the Family of Psittacidae, or Parrots (1832). The Society's copy is one of only a handful in the world thought to survive with a full set of plates.

(Left) Hyacinthine Macaw

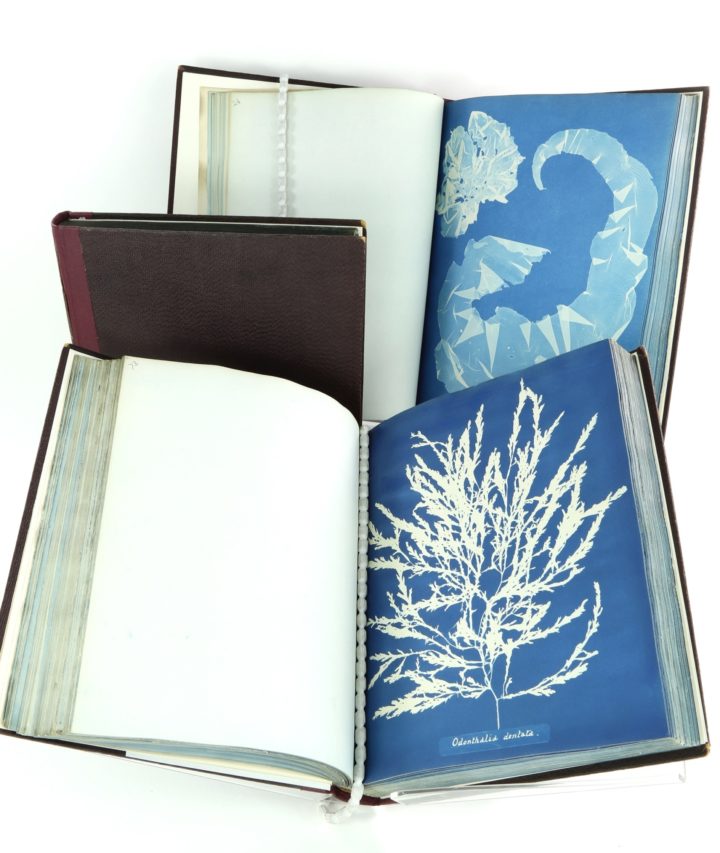

Anna Atkins was a 19th century English botanist and photographer. She is regarded by many to have produced the first photographic book, withPhotographs of the British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions(1843) representing a leap forward both in printing techniques and the art of photography.

The Achilles Morpho (Morpho achilles) is one of South America’s most beautiful butterflies, and the specimen that Carl Linnaeus used to give it a name has been kept in Burlington House for over 150 years. It was also a source of inspiration for the German-born naturalist and engraver Maria Sybilla Merian, who depicted it in her remarkable Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium. The Society holds the colour 1719 edition, which has later cross-references to Linnaean specimens pencilled beneath many of the engravings.

Artefacts

The Society holds many iconic artefacts that symbolise scientific discoveries and observations from the 18th century to today.

This microscope belonged to Robert Brown, the Scottish botanist famous for observing the ceaseless jostling of microscopic particles in 1827 (due to molecular movement) and subsequently called ‘Brownian motion’. It provided evidence of the existence of atoms and molecules and was a crucial basis for modern atomic theory. Watch how its tiny hand-ground lenses brought the microscopic world to life.

The Society holds William Keble Martin's drawings, paint-box and microscope, all of which were used for his well loved Concise British Flora in Colour, published in 1965 when Keble Martin was 88. It contains 1,400 species of plants and has been the inspiration for many budding botanists ever since. Listen to Curator of artefacts Glenn Benson (V&A) talk evocatively about Keble Martin's paint-box and book at the launch event of L:50 (at 42:59).

Want to find out more about our building and our collections?

- Watch our fantastic array of videos, that provide introductions and insights on many topics of natural history.

- Read our Blogs on all aspects of our collections and varied scientific subjects.

- Book a place on our regular Treasures Tours of the building and collections.

- Buy our book highlighting 50 iconic objects, stories and discoveries: L: 50 Objects, Stories and Discoveries from The Linnean Society of London..

- Delve into our online catalogues, including the library and archives catalogues, as well as the digitised collections, allow for more in-depth exploration of our wonderful collections.

Our neighbours in New Burlington House

Since 1874, New Burlington House has been home to a group of Societies as a meeting place for the arts and sciences. Our five neighbours in the courtyard are: