Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

The Tale of the Linnean Society

Beatrix Potter and her interactions with the Linnean Society of London have been the subject of much scrutiny, particularly regarding her treatment by the Society. Here we look at what our archives tell us.

Dr John Marsden, Executive Secretary of the Linnean Society, founded in 1788, acknowledged Potter had suffered an injustice at the hands of his early 20th century predecessors: "She was treated scurvily by members of the society. The only consolation is that if she had become a scientist she may never have written her books."

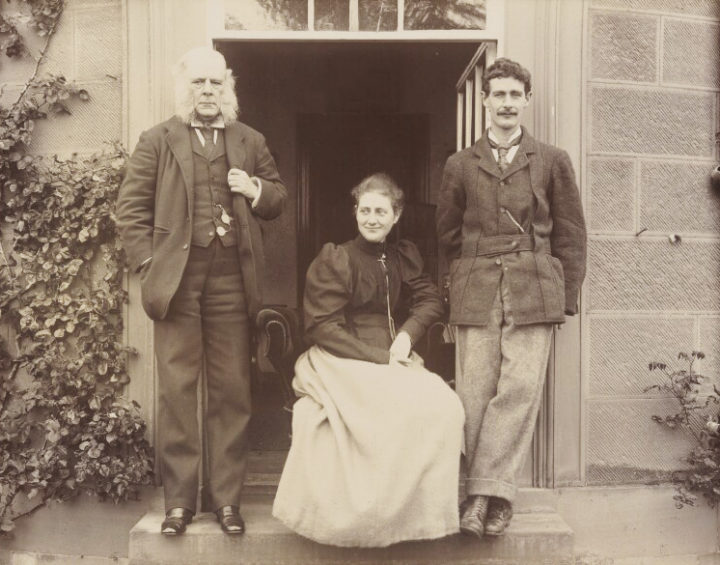

Beatrix Potter with her father Rupert (left) and brother Walter Bertram Potter (right) in 1894. © NPG P1822

Scientific Papers in the Victorian Era

One of the most frequent interpretations of her treatment is that a scientific paper she submitted for publication was rejected outright—but that is not the case. It is also reported that Beatrix Potter was not allowed to present her own paper at the Society because she was a woman. While it is frustratingly true that women were not admitted as Fellows (or members) of the Society until 1905 (which was unfortunately the case for many learned societies at the time), the accepted practice was that papers were always read by someone other than the author. Usually, the Society’s Zoological or Botanical Secretaries would have read papers within their remit. Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace (for varying reasons) were also not present at the reading of their ground-breaking joint paper On the Tendency of Species to form Varieties; and on the Perpetuation of Varieties and Species by Natural Means of Selection in 1858.

Potter the Scientific Illustrator

We know that Potter was a capable and enthusiastic mycologist—she consulted John Stevenson’s Mycologia Scotia (1879) as well as Oscar Brefeld’s extensive works—though she, in jest, stated the latter was ‘unreliable and like Dacrymyces’…a jelly fungus that changes shape! She studied different fungi and posited theories about the germination of spores; by 1896, a year before she submitted her paper to the Society, she was successfully growing spores of various fungal species on glass plates and tracking them under the microscope.

Potter’s strengths lay in her meticulous observation and artistic prowess. There is no doubt that she was a consummate illustrator who closely observed and faithfully recorded what she saw. Her correspondent, the mycologist Charles McIntosh—who supplied fungal specimens to Potter, and guided her painting—recognised her wonderful draughtsmanship. Having known McIntosh since the age of four (he had also been at one time the family postman), he encouraged her and helped with identifying species; eventually she would go on to produce over 350 illustrations of fungi.

Her uncle, Sir Henry Roscoe, introduced her to someone who would go on to become another Potter supporter: George Massee, successor to Mordecai Cubitt Cooke as Keeper of Lower Cryptogams at the Royal Botanic Gardens in Kew. In fact, it was Massee who read her paper at the Linnean Society. According to Potter expert Professor Roy Watling, Massee recognised in Potter “a draughtsperson when he saw one” and that he:

realised that Beatrix Potter was a wonderful illustrator. She illustrated the fungi precisely, not something that she would have copied out of a book. She illustrated what she saw in nature.

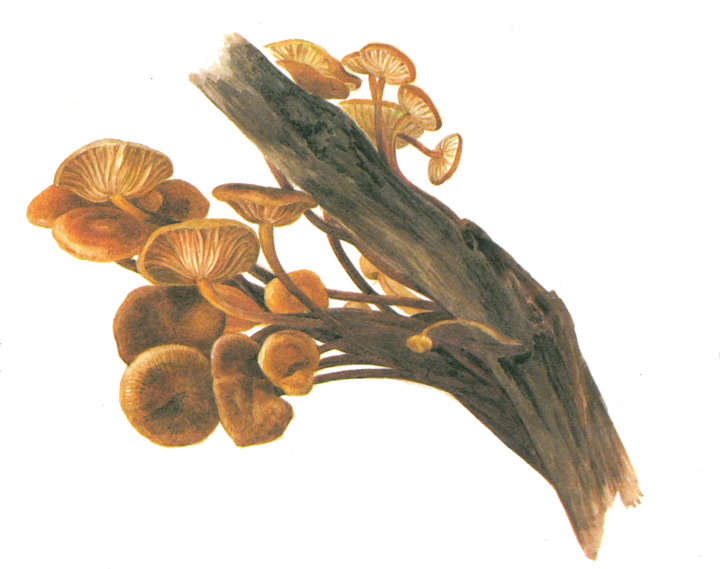

Potter's illustration of Flammulina velutipes, the subject of the paper she submitted to the Society. © Armitt Museum | https://www.armitt.com/

Indeed, the spores of Tremella in her paintings were not formally described until some 45 years later—she was illustrating what other people did not even see, and she was continually asking questions in her letters to McIntosh, especially regarding the possibility of intermediate species.

However it should be acknowledged that modern critics have queried one or two of her theories, particularly when looking at her diary, which was written in code and translated and published in the 1960s. A mistranslated footnote led some historians to believe that Potter, ahead of many of her contemporaries in the field, believed lichens to be a closely connected combination of fungi and algae, which we now know to be true thanks to the pioneering work of Swiss botanist Simon Schwendener. In reality Potter believed the opposite, that lichens were ‘stand alone’ organisms, which is what many mycologists believed in the late 1800s.

The Submitted Paper

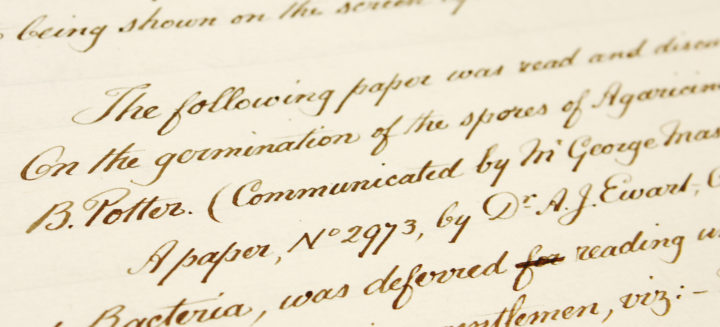

Helen B. Potter, as she called herself in 1897, submitted her paper ‘On the germination of the spores of Agaricineae’ to the Society. By all accounts, she had invested a considerable amount of time on the manuscript’s preparation, and according to Watling, decided that of “about 50 different species […] she only chose one, that of Collybiavelutipes (now Flammulina velutipes) for her paper”. The Society’s hand-written records show that her paper (designated No. 2978) was “read and discussed” on 1 April 1897 but then withdrawn, by Potter, on 8 April, and never resubmitted. Some additional work was required on the manuscript before it could appear in print, but it seems the work was never carried out. (It should be noted here that very often, authors were required to make changes before publication.) In September 1897 she wrote to McIntosh:

My paper was read at the Linnean Society and ‘well received’ according to Mr. Massee, but they say it requires more work in it before it is printed.

Unfortunately, because she withdrew the paper and did not return an amended version for publication, we do not hold any version of it in our archives.

The Minute Book shows Potter's submitted paper was read out at the Society in 1897 by George Massee. © The Linnean Society of London

The Legacy

The V&A Museum library holds many Potter illustrations of germinating spores, and other stunningly accurate mycological drawings are held in the wonderful Armitt Museum in Ambleside, Cumbria, north of Potter’s home at Hill Top. These drawings illuminate the scale of her talent as a botanical artist; their accuracy meant that they were actually used to identify fungi. Without her paper we can’t speculate on her potential scientific career, but her illustrations show that she was driven, analytical and observed specimens in infinitesimal detail. She dared to bring her own ideas to the ‘professional’ table during a time where women were not always seen as equal—an incredible part of her legacy.

For more information on Beatrix Potter's mycological studies and her relationship with the Linnean Society, read Professor Roy Watling's detailed piece in The Linnean (16(1): 24–31)