Botany

The Linnean Society’s Founder, James Edward Smith, saw himself as the successor to Carl Linnaeus when the Linnaean specimen and library collections were brought from Sweden to England. Like Linnaeus, Smith was first and foremost a botanist, making many connections with naturalists and building a botanical legacy on the Society’s growing reputation.

'Portlandia grandiflora', James Sowerby (artist), James Edward Smith, Icones pictae plantarum rariorum descriptionibus et observationibus, Vol. 1, Pl. 6 (1790, P 582.4 SMI)

Linnean Society Founder Sir James Edward Smith (1759–1828) and English naturalist, mineralogist, and illustrator James Sowerby FLS (1757–1822) worked together on many occasions, including the 36-volume work English botany, the masterpiece Flora Graeca, and A specimen of the botany of New Holland (the first published book on the flora of Australia). This plate is taken from their stunning work Icones pictae...Coloured figures of rare plants, which was published privately by Smith, and inspired by his friendship with Mary Watson-Wentworth (1735–1804), the dowager Marchioness of Rockingham. Her husband was Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain twice. After her husband's passing, Lady Rockingham's focus became her garden and expanding selection of plants, many of which would influence the images produced for Icones pictae. We chose Portlandia grandiflora, commonly known as the bell flower, as Lady Rockingham gifted a Portlandia flower to Smith as their friendship grew. The species is native to Jamaica and was first described by Linnaeus in the second volume of the 10th edition of Systema naturae (1759).

'Bohea Tea', John Coakley Lettsom, The natural history of the tea-tree, Section VIII: Varieties of Tea (1799, CQ 642)

The author of this book, English physician John Coakley Lettsom FLS (1744–1815) quotes Finnish-Swedish botanist Pehr Kalm (1716–1779) from his Travels into North America (1772) in Section IV (Origin of Tea) in The natural history of the tea-tree: 'Tea is differently esteemed by different people, and I think we would be as well, and our purses much better, if we were without tea and coffee. However, I must be impartial and mention in praise of Tea...on such journies [sic] as mine, through a desart [sic] country, where one cannot carry wine, or other liquors, and where the water is generally unfit for use, as being full of insects. In such cases it is very pleasant when boiled, and Tea is drank with it; and I cannot sufficiently describe the fine taste it has in such circumstances. It relieves a weary traveller more than can be imagined...on such journies [sic] Tea is found to be almost as necessary as victuals.' Although Bohea Tea can have wide-ranging references, depending on the time and place, in Lettsom's The natural history of the tea-tree, there are five types of Bohea Teas: 1) 'Soochuen, or sutchong'; 2) 'Camho, or soumlo'; 3) 'Cong-fou, congo, or bong-fo'; 4) 'Pekao, pecko, or pekoe', and 5) 'Common bohea'.

'The Maggot-bearing Stapelia', Peter Henderson (artist), Robert John Thornton, The temple of flora, or garden of nature (1799-1807, P 582.4(084.1) THO)

Robert John Thornton (1768–1837) was an English physician and botanical writer. He was inspired by Linnaeus' work and set out to publish his ambitious New illustration of the sexual system of Carolus von Linnaeus. The work was in three parts: the first, a dissertation on the sex of plants according to Linnaeus; the second, preliminary observations on the sexual system; and the third, the lavishly illustrated plates with explanations, titled The temple of flora. The artists included Peter Henderson, Philip Reinagle, Abraham Pether, and Sydenham Edwards, with Thornton himself creating the illustration of the roses. Despite dedicating this huge undertaking to Queen Caroline, consort of George III, and holding a lottery to raise money for the expenses of this work, Thornton was unable to pique enough interest and the project left him almost destitute. The resulting book was an unusual blend of science, poetry and art, and received an unfavourable reception. Linnean Society Founder and President James Edward Smith put Thornton forward for Fellowship of the Society but he was not accepted, much to Smith's disappointment; gossip at the time speculated that some of the responsibility for this may have come from Joseph Banks and his Soho Square set. The Society's copy belonged to Smith and is inscribed with '...from his greatly obliged friend, and pupil, the Author'. The plates are now celebrated for their atmospheric representations. The star-shaped plant shown in our chosen plate is a Stapelia—it is a carrion flower, meaning it produces a smell like rotten meat to attract specialist pollinators like flies and beetles (as shown by the fly in the picture).

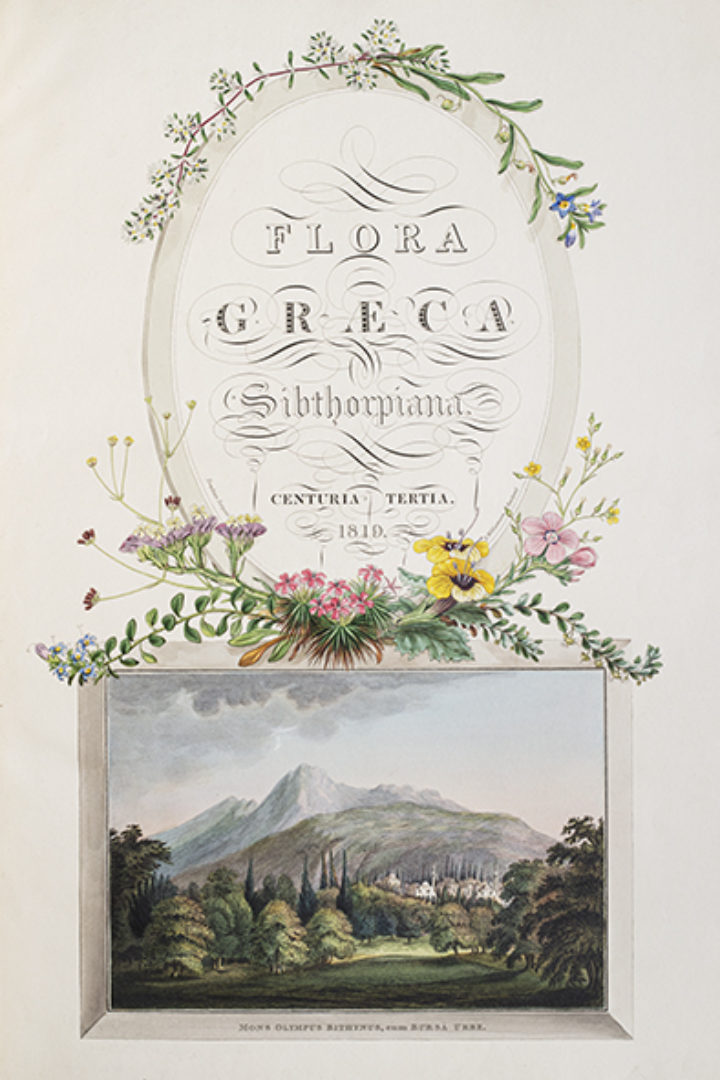

'[Title page]', Ferdinand Bauer (artist), John Sibthorp, Flora Graeca, Vol. 3 (1819, FF 914.95:582 SIB)

Flora Graeca was the work of English botanist John Sibthorp FLS (1758–1796) and Austrian botanical illustrator Ferdinand Bauer (1760–1826), with contributions from James Edward Smith, John Lindley, and James Sowerby. The publication was the result of a two-year survey of Greece and the eastern Mediterranean, with Sibthorp collecting and describing and Bauer producing sketches. Sadly, Sibthorp died before the work could be published, but in his will he bequeathed an estate to the University of Oxford, the revenues from which were to be used to finish the book. James Edward Smith, a personal friend of Sibthorp's, prepared the first seven volumes for publication using Sibthorp's herbarium specimens, diaries, field notes and an incomplete manuscript. Then, after Smith's death, John Lindley produced the remaining three volumes, with James Sowerby engraving the plates. It was a huge task, with 10 volumes holding 1,000 plates, all hand coloured, with an initial target of 50 sets (50,000 plates in total!). Eventually only the wealthiest subscribers could afford it, and 25 sets of the anticipated 50 were sold. Each volume has an engraved title page depicting a different location in Greece and reading 'Flora Graeca Sibthorpiana'; the one shown here depicts Mount Olympus. The Society holds all 10 volumes, and it is thought to be one of the most magnificent botanical publications ever undertaken.

'[Victoria Regia]', after drawings by Robert Schomburgk, John Lindley, Victoria Regia (1837, P 582.4p8 LIN)

Only 25 copies of this rather unwieldy book by English botanist John Lindley FLS (1799–1865) were privately published in 1837. Containing just three pages of description and the plate, it measures a huge 55.5 x 72 cm. Lindley dedicated the book to Queen Victoria, for whom the giant waterlily species was originally named (Victoria regia), and who had been crowned Queen that same year. In the book's dedication Lindley justifies the name, writing, 'It is therefore not less my duty than my inclination to concur with its zealous and enterprizing discoverer in distinguishing by your Majesty's illustrious name, by far the most majestic species in the family of the Nymphs—one of the most noble productions of the Vegetable Kingdom...' The giant waterlily’s path to ‘fame’ took a winding route; Eduard Friedrich Poeppig (1798–1868), a German naturalist, was the first European to see the plant in Peru in 1832. Then, it was again seen by German botanist Robert Hermann Schomburgk (1804–1865) in what was then British Guiana, as part of an expedition supported by the Royal Geographical Society. He sent back his collections and field notes to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, where Lindley would describe the plant in the book shown here. After attempts to grow the plant at Kew failed, seedlings were sent in 1849 to Joseph Paxton FLS (1803–1865), head gardener to the Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth House, who managed to get the plant not only to grow, but to bloom. Soon they appeared in glasshouses across Britain, sparking the Victorian craze for giant waterlilies. Famously strong enough to support the weight of a child, Paxton drew inspiration from the leaf structure when designing the Crystal Palace for the Great Exhibition of 1851. The species has since been renamed Victoria amazonica.