‘Exotic Attractions’: Conserving Engelbert Kaempfer's famous publication

Conservator Janet Ashdown looks at the importance and history of Carl Linnaeus's copy of Kaempfer's famous work

Published on 8th August 2023

Englebert Kaempfer (1651–1716) was born in Lemgo, Germany. He would go on to study philosophy and medicine at Königsberg on the Baltic coast before travelling to Sweden in 1681, where he took up a post as secretary to the Swedish embassy in Persia. Kaempfer was ambitious and wanted to make his name as a pioneer traveller, first in the Middle East and then throughout parts of Asia, gathering useful in-depth information about the lands he visited that would widen knowledge in the West. In his later years he would publish Amoenitatum exoticarum (c. 1712), produced in five volumes or ‘books’, which gave a comprehensive account of his observations in the East.

The Swedish embassy arrived in Persia in 1683, and for nearly two years Kaempfer travelled with the embassy, recording details of everything from the oil wells in Baku to the agriculture of the Caspian coast, logging the minutiae of industry, architecture, culture and government.

Plate of a cavalcade heading towards the sacrifice of a camel from Kaempfer's Amoenitatum exoticarum. (The Linnean Society of London)

Kaempfer remained after the embassy left Persia, and in 1685 he was employed as a physician in Gamron (Bandar Abbas) whilst continuing to study places, industries and species of interest. His detailed study of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) in book IV of the Amoenitatum was for many years disregarded, despite its great cultural and economic importance.

(TOP) Plate of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) from Amoenitatum exoticarum, showing varying stages of growth; (BOTTOM) The fruits of the date palm, a culturally and economically important species. (The Linnean Society of London)

Onwards to Japan, then home

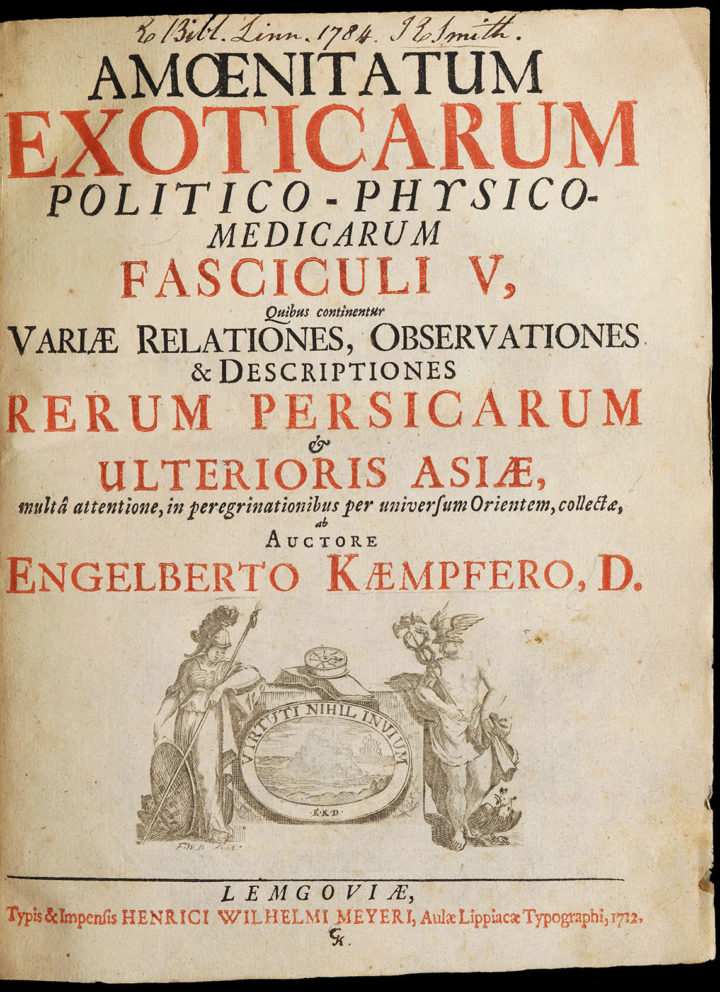

Title page from Carl Linnaeus's copy. (The Linnean Society of London)

In 1688 he embarked by ship to India and continued his travels visiting Ceylon, Batavia (Jakarta) before moving on to Japan where he had accepted a position as a surgeon, visiting Siam (Thailand) en route. He arrived in Nagasaki in 1690 and during the next three years he collected information about the people, flora, geography, history and economy of Japan. Kaempfer was a major source of information about Japan until 1854 when the borders were officially opened to foreigners. Book V of Kaempfer’s Amoenitatum is his Flora Japonica.

Kaempfer returned to the Netherlands in 1693 and gained his PhD in medicine at the University of Leiden. He returned to his birthplace of Lemgo in 1694 where he practiced medicine. Unfortunately, his ambition to obtain a Professorship at a leading university was never realised. Amoenitatum was the only work published during his lifetime, produced rather later in life, and was sadly a disappointment to Kaempfer as he felt his many detailed drawings were poorly reproduced by the printer. It remained little known but important; the information he had gathered on his travels was rarely referenced. He contributed a great deal to 17th and 18th-century knowledge about Persia and Japan, and his research was of a high quality. Kaempfer exemplified the Age of Enlightenment, his work being guided by reason rather than by religious, political or social convention.

After his death, his herbarium and manuscript papers were sold to Sir Hans Sloane, which then were left to the British Museum. Kaempfer’s herbarium now makes up volumes 211 and 213 of the Sloane Herbarium at the Natural History Museum in London, and his manuscripts are housed at the British Library. Some of his works have recently been translated into English, including the first four books of Amoenitatum, which cover his travels in Persia. The final and fifth book covering his travels in Japan is yet to be published in English.

Conservation of Carl Linnaeus’s copy

There were, however, some people who took a very keen interest in Kaempfer’s published accounts, and one of them was Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778). With Kaempfer being one of the earliest collectors to bring specimens back to Europe from Japan, his descriptions and illustrations were heavily consulted by Linnaeus. In his book Order out of Chaos, botanist Charlie Jarvis writes: ‘Nearly all of the copperplates depicting plants were cited by Linnaeus, and many of them […] are types.’

The beautifully illustrated copy of Amoenitatum shown here is Linnaeus’s own copy (LS Library Reference: BL.311), part of his personal library, and was in need of conservation through the Linnean Society’s AdoptLINN book adoption scheme. It was generously adopted by a Linnean Fellow, and for the past few months has been undergoing conservation.

The boards had become detached and the spine had split down the centre, leaving the adjacent sections to become loose. Some of the plates, particularly those that fold out, had minor tears. In order to repair the split in the spine, the original leather covering the spine had to be removed. This was covered in Japanese tissue to prevent it disintegrating, but unfortunately the original leather was too thin and worn to be re-used.

The sewing cords, which were also worn and frayed, were strengthened with new linen cords and the loose sections were sewn back into place through the reinforced cords. Torn plates were repaired and the edges of the text block were lightly cleaned.

The final conserved book, made possible through AdoptLINN.

In order to facilitate any future repairs, the spine was covered with a moulded hollow spine made from Japanese paper, reinforced with aero linen. This can be easily removed if required without further damage to the original text block. The boards were then re-attached utilising the new cord supports and the linen reinforcement, and a new leather covering for the spine was made from calfskin. Damaged corners of the boards were repaired and recovered, and scuffed board edges were consolidated with paste.

If you would like to adopt one of our historic books for yourself, a relative or a friend, explore our AdoptLINN page to see what titles are available for conservation and adoption. Your support could ensure many books are available to study for years to come.

Janet Ashdown, Conservator

Jarvis, C. (2007). Order out of Chaos: Linnaean Plant Names and their Types. London: The Linnean Society of London.

Kaempfer, E. (2018). Exotic attractions in Persia, 1684–1688: Travels and Observations (translated and annotated by Willem Floor and Collette Ouahes). Maryland: Mage Publishers.