International Women's Day 2023: Celebrating Women in Natural History

We highlight the lives and achievements of eight women in the history of biology, suggested by our staff, Fellows, and members of the public

Published on 7th March 2023

Last year, the Linnean Society marked International Women’s Day by celebrating ten women who’d made an historic contribution to the study of biology. The article, featuring a selection of biologists nominated by our staff and Fellows, ended by inviting readers to nominate their own natural history heroes for a follow-up article this year.

We were bowled over by the number and diversity of responses we received, and it’s our very great pleasure to showcase some of those nominations here. Thank you to everyone who sent in their suggestions!

Mary Anning (1799-1847)

Anning with her dog, Tray, painted before 1842. Public Domain.

Mary Anning was an English fossil collector and paleontologist who became well-known in her own lifetime for a series of remarkable discoveries along the Jurassic Coast in Dorset. At twelve years old she discovered the first correctly-identified ichthyosaur skeleton, and went on to discover and identify the first two nearly complete plesiosaur skeletons, among a number of other fossil fish discoveries. Her observations also helped establish that coprolites, known as bezoar stones at the time, were in fact fossilised faeces.

Mary Anning's statue in Lyme Regis. Image courtesy of Carbonmoon, licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0.

Anning struggled financially for much of her life, and as a woman was ineligible for membership of most scientific and professional bodies of the time, including the Geological Society of London. She did not always receive full credit for her work. She did, however, enjoy the patronage of friends in the scientific establishment, including the early paleontological artist and geologist Henry De la Beche, who sold copies of his work for her benefit.

Anning’s fame increased after her death in 1847, with a number of romanticised (and variably accurate) literary and cinematic portrayals establishing a “myth of Mary Anning”. These include the 2009 Tracy Chevalier novel "Remarkable Creatures" and a 2020 feature film "Ammonite" starring Kate Winslet.

Following a long public campaign, Anning was finally immortalized with a statue in her home town of Lyme Regis in 2022.

Henderina Scott (1862-1929)

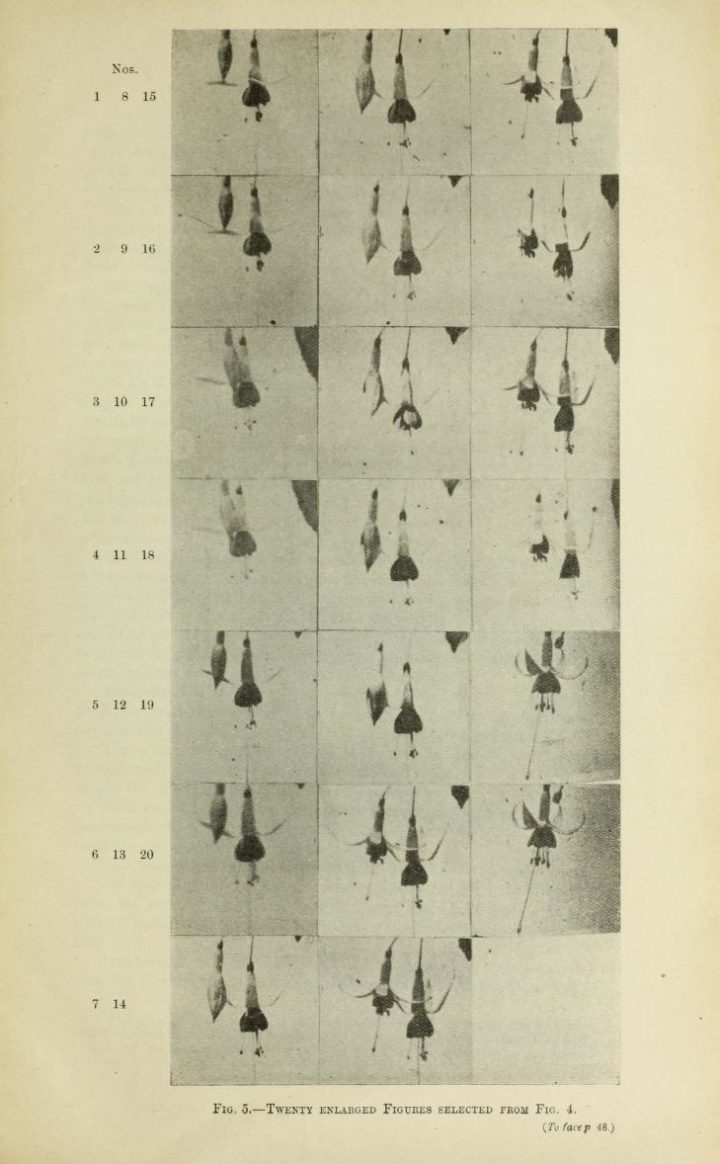

Time lapse images of the opening of a Fuchsia flower, taken by Henderina Scott. Image courtesy of the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Henderina Scott (née Klaassen) was an English botanist who pioneered the use of time-lapse photography. She was born in the Surrey suburbs to Hendericus Klassen, a successful German émigré and enthusiastic amateur scientist who instilled a love of natural history in his children. While studying at the Royal College of Science (later a part of Imperial College), she met the noted botanist Dukinfield Henry Scott, who she married in 1887.

Scott’s lasting contribution to science was her innovative use of time-lapse photography to capture the movement of plants. After 1900, she used a device known as a Kammatograph to record photographic images on a glass disc that could then be projected in a manner similar to a magic lantern.

Her images were displayed at several scientific meetings, including the conversazione of the Royal Society in 1904. She was elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society in 1905.

Libbie Hyman (1888-1969)

Libbie Hyman (1888-1969). Public Domain.

Libbie Hyman was an American zoologist who wrote a number of influential works on invertebrate zoology.

Hyman was born in Des Moines, Iowa, to Joseph Hyman and Sabina Neumann, Russian/Polish Jews who adopted the surname “Hyman” when they moved to the United States. The family was not well-off, and home life was hard, but Hyman demonstrated an early love of science and learning. Flowers rather than animals were an early passion, and Hyman taught herself the principles of classification from her father’s copy of Asa Gray’s Elements of Botany.

After a number of dead-end jobs—including a stint pasting labels in a cereal box factory—Hyman entered the University of Chicago on a one-year scholarship. She soon switched focus from botany to zoology under the mentorship of Charles Manning Child, graduating with a BSc in 1910.

Today, Hyman is best remembered for her accessible laboratory guides for elementary zoology and vertebrate anatomy—which became bestsellers—and her monumental six-volume work The Invertebrates, which began publication in 1940, and drew on her knowledge of several European languages.

Hyman was awarded the Linnean Medal of the Linnean Society of London in 1960.

Dorothea Pertz (1859-1939)

Dorothea Pertz (1859-1939). Item PP-P-13. Image © Linnean Society of London.

Dorothea Pertz was a British botanist famous for her collaborations with Francis Darwin, Charles Darwin’s third son, and for being one of the first women elected to Fellowship of the Linnean Society of London.

From a wealthy and well-connected family, Dorothea’s home life was one of comparative social and intellectual freedom. Her father, Georg Pertz, was a progressive intellectual and ardent supporter of Darwinism, and was connected to the prominent Lyell family through her aunt, the botanist Katherine Murray Lyell.

Pertz spent most of her youth in Berlin, where her father worked as Royal Librarian, moving to Florence after her father’s death in 1876. Later she returned to England and was admitted to Newnham College, Cambridge in 1882. She gained second-class honours in the Natural Sciences tripos in 1885, but as women were not allowed to take degrees at that time, she was only able to graduate in 1932.

Dorothea’s main contribution to botany came via a series of papers on plant physiology published with Francis Darwin, as well as a collaboration with William Bateson on plant inheritance. She also published at least two papers independently, usual for a woman at this time. Following Darwin’s retirement—and a few years of disappointment in what was a rapidly changing field of research—Pertz devoted her time to indexing the vast body of literature on plant physiology in German.

She was elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society in 1905, and her likeness appears in our library.

Jane Loudon (1807-1858)

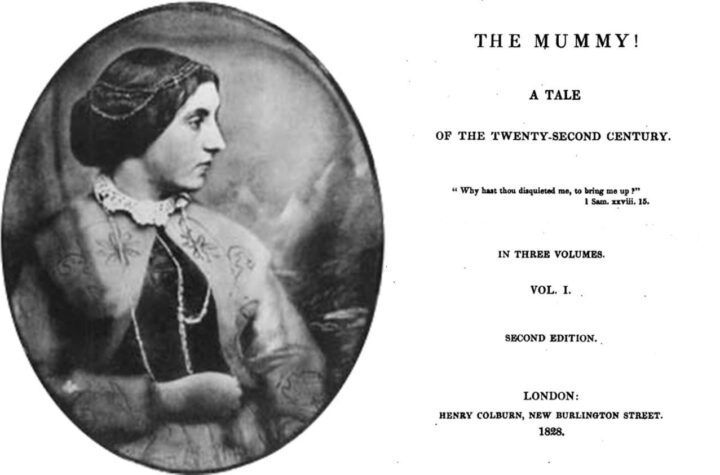

Jane Loudon is already a hero to many for her work in a number of fields, including botany, horticulture, and early science fiction. Born in Birmingham in 1807, Loudon pioneered a new genre of English fiction with her sensational tales of Egyptian mummies, and later—through her marriage to the gardener John Loudon in 1830—introduced middle-class English ladies to the joys of gardening through her accessible and affordable manuals.

Her early forays in science fiction came early in life—aged just 20—with the publication of The Mummy! A Tale of the Twenty-Second Century; a work of fictional prognostication that sought to imagine a Britain of the future. Unlike other speculative fiction of the time Loudon didn’t limit herself to imagining political changes, but a range of future innovations across culture, society, fashion, arts and technology (even predicting a sort of early internet). Despite its lurid title, Loudon’s work was generally well-received. You can read more about her fictional work in this article, recently published by the Linnean.

Possibly her greatest legacy to science, however, came in the form of her series of gardening manuals. The first of these were published in the 1840s, as the spiralling costs of her husband’s book Arboretum et Fruticetum Britannicum put the family into considerable debt. Innovative for their explicit focus on a female audience, they were also notable for charming illustrations by Loudon herself.

Jane Loudon died comparatively young, at age 50. In 2008, a blue plaque was installed in her honour at Kitwell Primary School, Birmingham, near the site of Kitwell House, where she was born. John Loudon was a Fellow of the Linnean Society, and many of her works survive in our library.

Savitri Sahni (1902-1985)

Savitri Sahni (1902-1985)

Savitri Sahni was an Indian paleobotanist, and President of the Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleosciences from 1949 to 1969.

She was born in Lahore in 1902 to Rai Bahadar Sundar Das Sur, a school inspector. She enjoyed taking botanical excursions with her husband, Birbal Sahni —also a paleobotanist—and at his sudden death in 1949 assumed the presidency of the Paleosciences Institute he had led. She reputedly wore white silk for the rest of her life as a symbol of mourning and widowhood. Sahni died in 1985, aged 82, in Lucknow. Her home was converted into a museum, and the residue of her estate used to support the work of the Paleosciences Institute.

Ellen Hutchins (1785-1815)

Ellen Hutchins was an Irish botanist well-known for her work with seaweeds, mosses, lichens, and liverworts. She discovered many new species in her native Bantry Bay, and contributed botanical illustrations to many scientific publications of her time.

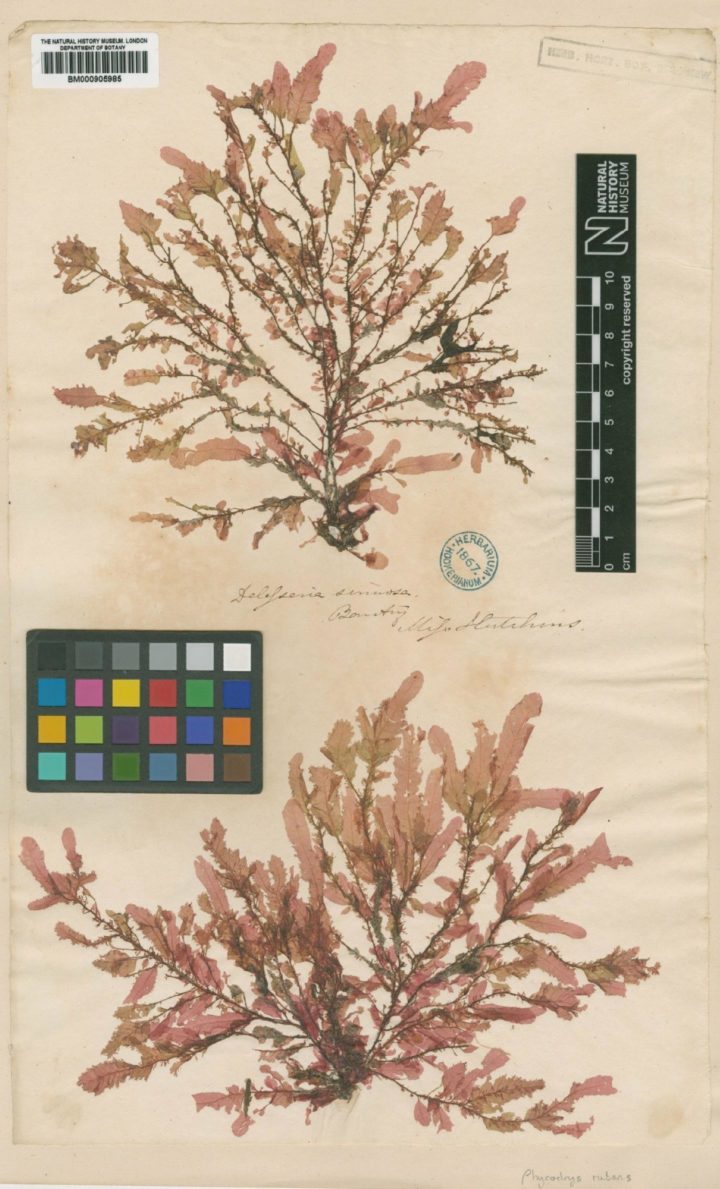

Specimen of Phycodrys rubens (L.), collected by Ellen Hutchins. Courtesy of the Natural History Museum, London. Licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0.

Born in Ballylickey, her father died when she was two years old, leaving Ellen in the care of her mother and six surviving children. She was sent away to school near Dublin, where her health appears to have deteriorated (perhaps as a result of poor nutrition). Taken in by a family friend, Ellen’s health recovered and she was encouraged to pursue an enthusiasm for botany and natural history. Returning to Ballylickey, Hutchins spent much time outdoors and devoted much of her short life to the study of cryptogams. The flora of this part of Cork was poorly surveyed at this time, and Hutchins’ work provided much valuable early data (including many first-time identifications, for which she became well-known). Between 1809 and 1812 she prepared an immense list of the nearly 1,100 plants she had collected and prepared, and recorded over 400 vascular plants, around 200 species of algae, 200 bryophytes and 200 lichens.

By 1812 Hutchins’ health had once again begun to decline, and she died tragically young, aged 30, in 1815. Her legacy lives on in her magnificent archive and specimen collections—many of which can be found in the Natural History Museum and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew—and in the Ellen Hutchins Festival, held each year in her native Bantry.

Margaret Plues (c.1840-1903)

Calamagrostis lanceolata, and Aira caespitosa, from Plues' British grasses: an introduction to the study of the Gramineae of Great Britain and Ireland (1867). Courtesy of Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Margaret Plues was a British botanist best known for her popular guides to the British ferns and mosses. Born in Ripon, Yorkshire, to William Plues, a clergyman, and his wife Hannah, she came from a large, close-knit family with a love of the outdoors.

She began writing in her early 20s, focussing on the emerging genre of “popular science” guides for a lay audience. Her first books documented her own botanising trips in the English countryside under the series title “Rambles in search of…”. She also wrote more scholarly works, mostly on ferns and grasses, concentrating on their propagation and geographical distribution. Some fictional works—a novel and some short stories—were published under the pseudonym “Skelton Yorke”.

Plues’ later life was characterised by financial instability, and her dedication to charitable endeavours. She converted to Roman Catholicism in 1866, and moved to London in 1870 to take charge of a workhouse recently founded by a priest, Thomas John Capel. Capel mismanaged the workhouse’s finances and borrowed extensively from Plues’ personal funds. When he eventually went bankrupt, Plues herself was ruined. By 1891 Plues had moved to Surrey, to live with one of her brothers, eventually entering the convent in Weybridge (where she would eventually become Superior General)—regaining a modicum of stability at the end of an eventful life.

Unless otherwise indicated, all images in the public domain.

Banner image: Plate from Jane Loudon, The ladies' flower-garden of ornamental greenhouse plants. London: William Smith, 1848. Image courtesy of Biodiversity Heritage Library.