The Linnean Society Loose Letters Collection: The Weird and the Wonderful

Published on 15th June 2018

Since October, I have been cataloguing the loose letters collection, which mostly ranges in date from 1800 to 1990. The majority deal with membership concerns such as membership applications, paying fees, attending meetings, and receiving copies of publications.

Members and non-members often sent in descriptions or photographs of plants and animals asking for help in identification. Requests were usually straightforward, but sometimes they could be a little more unusual. A. Thomson, in 1901, wrote rather desperately from the Zoological Society asking if the Linnean Society could give the name and address of any gentleman who might be able to supply trained hawks for the Sultan of Morocco. Presumably the Linnean Society was of some help, as someone has written down an address on the letter. In 1993, Luis Villar Corzo wrote to the Society to advertise his stock of live alpacas (400 females and 40 males). Given the lack of space in the Society, they seem to have declined his offer.

Edwin Gold became rather excited in 1954 by reports of the Loch Ness monster, believing it to be similar to the legendary Polynesian sea-monster, the Taniwha. He described in great detail his reasons for believing in its existence and was puzzled by ‘the indifference shown by scientists to the affair.’

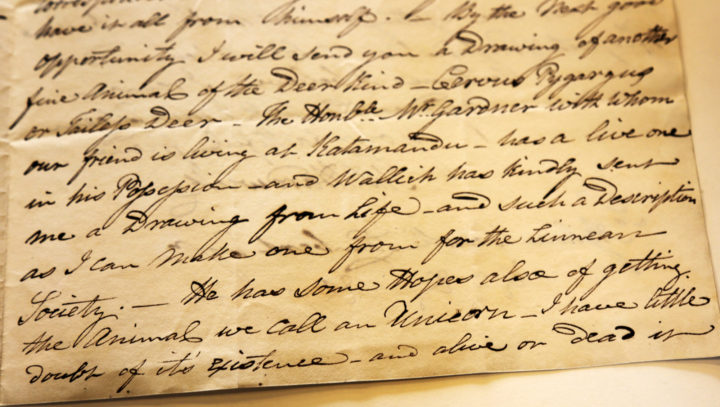

Thomas Hardwicke (1821) went even further with his belief in the unicorn. Having proudly described his specimens (including a bear skin, Nepalese wild sheep horns and musk deer), he then referred to his friend [Nathaniel] Wallich, who

has some hopes also of getting the animal we call an Unicorn – I have little doubt of its existence – and alive or dead it will be a great acquisition to Natural History

Despite several subsequent letters detailing more specimens, the promised unicorn was never mentioned again.

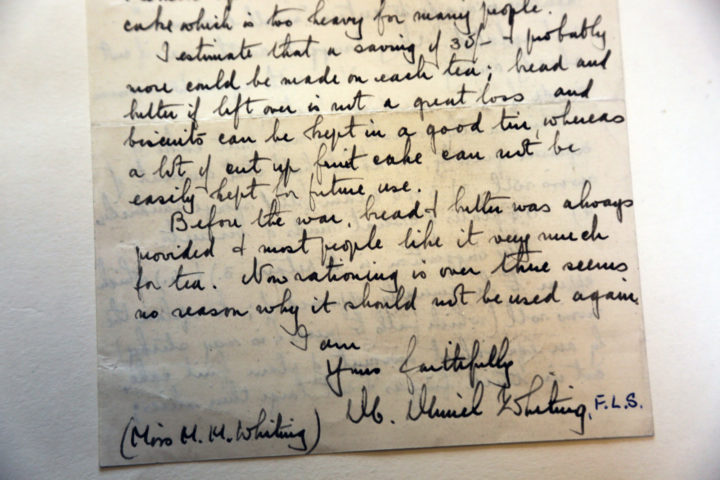

The domestic affairs of the Linnean Society occasionally came under scrutiny. In the bleakness of post-war rationing, the Society continued providing tea, with occasional help, as a letter from Monie Watt (1948) shows. She posted a parcel of tea, dried milk, and ‘old fashioned Basin cloths’ as a contribution to the Society. In 1956, M. Muriel Whiting had other thoughts about the tea provided. For reasons of economy she suggested replacing the swiss roll provided (‘very sticky’) with plain fruit cake, and replacing the rich fruit cake with bread and butter (which she believed many Fellows would prefer).

Occasionally more serious matters occurred. An imposter was seen in the Library in 1844. Luckily, S. Symons appeared to know the identity of the man, John Berrington, described as ‘a person wearing a clerical coat.’ Symons had more information: ‘he was guilty of some very unclerical acts’ and was ‘a most accomplished swindler’ who has spent time in prison.

Other members gave accounts of their exploits and the stories behind their specimens.

William Markwick’s letter in 1795 provides one of the saddest stories of specimen collecting.

You may remember that in the year 1789 I sent you a specimen of the Scaup Duck anas marila together with the Tippet Grebe [Podiceps cristatus], but your Servants thinking them Delicacies for the Table dressed them for your Dinner, before you could examine them as a Naturalist.

Luckily he sent some more specimens (obtained by sending his servant to ‘shoot what Birds he could’) which hopefully reached his correspondent without incident.

Some letters appear to have very little relevance to the Society. A letter from 1782 from Lewis Rosey was a touching plea to his uncle to reply to his letters. How the letter came to be at the Society is unclear; his uncle was in Lausanne, while Lewis himself was an apprentice to a watch maker near Soho Square. He wrote with a wish that they would spend some time together in the future, and that ‘we must not think of that the time being at to great a distance of and a great many things may happen between this and then.’

This fascinating collection demonstrates the variety of the Linnean correspondence over the years and makes rewarding reading. The letters have now been catalogued and will soon be available on the CALM archive catalogue.

Anne Courtney, Volunteer