Out on a Limb: How Primates Jump in the Trees

How early primates evolved to jump safely from the narrow branches of the arboreal canopy. Written by Grégoire Boulinguez-Ambroise & Jesse W. Young.

Published on 3rd February 2026

Decades of research have suggested that early primates were a highly arboreal radiation (spending their life in the trees) that evolved in the fine terminal branches of the canopy. Study of their fossils also suggests selection for enhanced jumping ability during their early evolution. In the fine-branch environment, supports are narrow and compliant with the potential to both compromise jumping ability and make jumping dangerous. Facing these challenges, what are the behavioural and morphological solutions that emerged in primates allowing them to jump safely in the canopy?

In this study [2, 3], published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, a team of researchers from Northeast Ohio Medical University (OH, USA) and Duke University (NC, USA) used an original experimental apparatus to evaluate the behavioural and anatomical correlates of leaping performance and reconsider the importance of leaping in primate evolutionary origins. We compared dwarf lemurs (primates) to tree shrews (not primates) — two animals of similar body size who tend to jump with approximately equal frequency. Tree shrews, however, are more terrestrial than dwarf lemurs. What jumping strategy is «best» in different ecological scenarios?

Why Jumping?

Figure 1: Bustard, Albatross and Elephant bird. Three male fat-tailed dwarf lemurs (Cheirogaleus medius) living at the Duke Lemur Center (DLC, NC, USA). With more than 200 animals across 13 species, the DLC houses the world’s most diverse population of lemurs outside their native Madagascar [1]. Photo: David Haring, DLC.

Jumping is a locomotor behaviour that proves crucial in a wide range of activities, from quickly avoiding predators, to acquiring resources, to finding a mate through spectacular courtship displays. Living in an arboreal habitat, a primary difficulty is the support discontinuity, especially in the canopy where branches are narrow and farther apart [4]. Bigger animals can use bridging to negotiate gaps but small animals depend on airborne manoeuvres such as jumping. The successful completion of these airborne manoeuvres represents a key target of natural selection and several arboreal mammals have evolved the capacity to jump in trees.

A bit of Physics

According to Newton’s laws of motion, the vertical height of a jump is determined by the velocity reached at take-off (i.e., the moment when the feet leave the ground). An animal has two strategies to increase take-off velocity: (1) push forcefully against the launching support by powerful contraction of the hip and knee extensors, or (2) increase push-off distance, typically by fully extending the hindlimb joints. A useful analogy is accelerating to enter a highway: you can reach the same speed by stamping on the gas pedal, or by gently pressing the pedal for a longer distance.

The Challenge of Jumping in a Fine-Branch Environment

In the fine-branch environment, supports are narrow and compliant. They have the potential to compromise the ability to jump and make it dangerous by absorbing some of the force produced against the launching support during push-off, and unpredictably returning this energy at random times and random directions. You might have experienced a similar phenomenon when trying to walk on a trampoline without tripping.

Tree Shrews Versus Lemurs

This research tested the hypothesis that primate behaviour and specialised anatomy represent a solution to the challenges of fine-branch jumping. Researchers compared the jumping morphology and biomechanics of a small-bodied arboreal primate, the fat-tailed dwarf lemur (Cheirogaleus medius, family Cheirogaleidae; Fig. 1), to a small-bodied arboreal tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri, family Tupaiidae, order Scandentia; Fig. 2). These two species are great models for a comparative biomechanical analysis: both are arboreal, of similar body size, and show similar locomotor repertoires, using leaping for ~20% of their locomotion [5, 6].

Brenda, female tree shrew (T. belangeri) living at the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo (CMZ, OH, USA). Tree shrews are small-bodied mammals ranging from India throughout Southeast Asia. Photo: Gina Wilkolak, CMZ.

Measuring in-vivo Jumping Performance

Researchers used an original custom-built apparatus, the ‘Jump Tower’ [7], to collect biomechanical data on maximal jumping performance. This experimental step combined instrumented force platforms with 3D calibrated high-speed cameras. The Jump Tower could be placed in the animals’ enclosures at the Duke Lemur Center (Durham, NC, USA) and Cleveland Metroparks Zoo (OH, USA) [7], and moved easily from one enclosure to another. The protocol did not require interactions (i.e., training) with animals, promoting the display of a more naturalistic behaviour. Within the tower, animals performed vertical jumps to perches of increasing height in order to access tasty treats. Forces generated during push-off (recorded by force plates) were processed to calculate several biomechanical parameters that the research team compared against micro-CT data quantifying bony features thought to reflect jumping ability.

Distinct Biomechanical Strategies

The tree shrews ended up being the champions. Tupaia belangeri reached the highest target, with the maximal take-off velocity of 3.66 m.s–1, allowing the animal to travel an airborne distance of 69 cm following take-off. In C. medius, the maximal take-off velocity recorded (3.09 m.s−1) allowed the animal to travel an airborne distance of 49 cm following take-off. However, tree shrew’s champion performance came at the potential cost of generating high forces to power such high jumps.

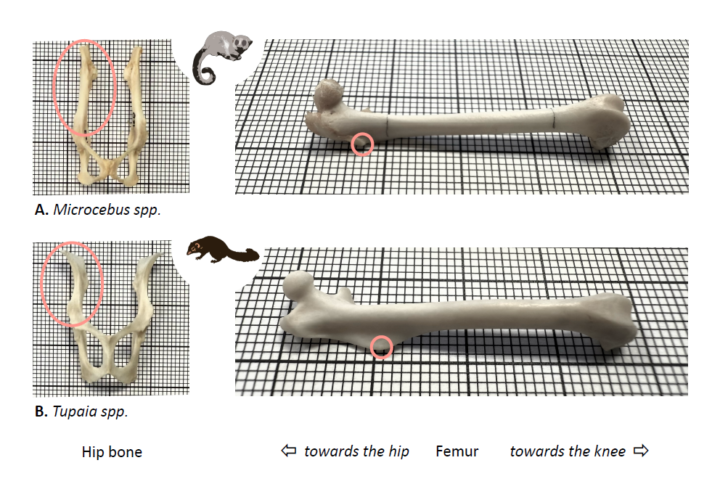

To increase take-off velocity (the primary determinant of jump height), T. belangeri prioritized force production and high mechanical power. This power-focused strategy corresponds with larger attachments and longer moment arms for hip and knee extensors (Fig. 3). In contrast, C. medius prioritized center of mass excursion over a longer push-off duration, a strategy enabled by their greater hip joint mobility (Fig. 3). In addition, C. medius used their powerful manual grasping abilities to reach above their heads and safely reach the same heights that T. belangeri required high take-off velocities to access (thus requiring lower force production from the dwarf lemurs).

Figure 3: Comparative views of hindlimb bones between A. Cheirogaleus spp. and B. Tupaia spp. LEFT: In anterior views of hip bones (left), note the relatively wider ilium (circled in pink) in the tree shew compared to the primate, specifically at the origin of hip extensor muscles (gluteal muscles). Relatively bigger attachment sites can correlate with relatively bigger muscles, facilitating force production in tree shrews. RIGHT: Anterior views of femurs (right) show the position of the third trochanter of the femur (circled in pink): an insertion site for the primary hip extensor muscle (m. gluteus superficialis). The position closer to the hip joint in the primate allows more mobility at the joint, facilitating limb excursion during push-off. In contrast, the more distal position in tree shrews provides greater leverage for the muscle, facilitating force production. Material (courtesy of Dr. Matt Borths, DLC Museum of Natural History): DLC 603 (C. medius), DLC RK24-00054 (T. glis). Photos on graph paper (mm): Grégoire Boulinguez-Ambroise.

Conclusion

The ability to minimise force production in the primate C. medius further supports hypotheses of frequent use of narrow, compliant supports during early primate evolution, allowing early primates to jump more effectively and safely in a small branch milieu.

Jumping for Joy: Fun Facts

- Dwarf lemurs can be bouncy but they also like to rest. Cheirogaleus spp. are the only primates known to be obligate hibernators in the wild. Current investigations at the Duke Lemur Center use this model for informing space travel [8].

- Tree shrews (Tupaia spp.) are known for their absentee maternal care system. Offspring are placed in a different nest from their mother’s. The mother only visits the newborns for nursing every other day. Louise Emmons, one of the few researchers having studied tree shrews in the wild, observed: “[The mother] jumped from tree to tree on slender understory saplings, without touching the ground anywhere near the nest tree. She usually did not run up or down the nest tree but jumped to it at the level of the entrance from a neighbouring treelet” ([9], p.172). The use of jumping to access the nest, combined with a minimal maternal-care system, prevents scent marking, suggesting a predator avoidance strategy.

References

[2] Boulinguez-Ambroise, G., Bradley-Cronkwright, M., Dunham, N.T., Yapuncich, G.S., Schmitt, D., Zeininger, A., Boyer, D.M. & Young, J.W. 2025. Comparative biomechanical analysis of jumping between the arboreal northern treeshrew (Tupaia belangeri) and the fat-tailed dwarf lemur (Cheirogaleus medius). Zool. J. Linn. Soc., 205, zlaf177. https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaf177

[3] Boulinguez-Ambroise, G., Boyer, D.M. & Young, J.W. 2025. Data and script from: Comparative biomechanical analysis of jumping between the arboreal northern tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri) and the fat-tailed dwarf lemur (Cheirogaleus medius). Duke Research Data Repository. https://doi.org/10.7924/r42235x15

[4] Young, J.W. 2023. Convergence of arboreal locomotor specialization: morphological and behavioral solutions for movement on narrow and compliant supports. In: V.L. Bels & A.P. Russell (Eds.), Convergent Evolution: Animal Form and Function. Cham: Springer, pp. 289-322. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11441-0_11

[5] Gebo, D.L. 1987. Locomotor diversity in prosimian primates. Am. J. Primatol., 13, 271-281.

[6] Granatosky, M.C., Toussaint, S.L.D., Young, M.W., Panyutina, A. & Youlatos, D. 2022. The northern treeshrew (Scandentia: Tupaiidae: Tupaia belangeri) in the context of primate locomotor evolution: A comprehensive analysis of gait, positional, and grasping behavior. J. Exp. Zool. A Ecol. Integr. Physiol., 337, 645-665.

[7] Boulinguez-Ambroise, G., Boyer, D.M., Dunham, N.T., Yapuncich, G.S., Bradley-Cronkwright, M., Zeininger, A., Schmitt, D. & Young, J.W. 2024. Biomechanical and morphological determinants of maximal jumping performance in callitrichine monkeys. J. Exp. Biol., 227, jeb247413. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.247413

[8] https://lemur.duke.edu/interstellar/

[9] Emmons, L.H. 2000. Tupai: A Field Study of Bornean Treeshrews. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Guest Author: Grégoire Boulinguez-Ambroise

Grégoire Boulinguez-Ambroise is a biological anthropologist. He got his PhD in Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Biology at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris (MNHN, France). He develops comparative and integrative approaches to reveal relationships between biomechanical performance, behaviour and morphology related to key functions, like grasping and jumping. He works with a wide diversity of primate species to understand how functional requirements imposed by the environment have driven the evolution of the underlying anatomy and function. His original experimental apparatus bring new evolutionary insights into primate evolution, but also act as fun enrichments for animals in Zoos!

Guest Author: Jesse W. Young

Jesse W. Young is a Professor of Anatomy at Northeast Ohio Medical University. The Young Lab studies how animals move, asking how bodies, growth, and environments work together to shape what animals can do—from a baby's first steps to the movements that define entire evolutionary groups. A major focus of our research is how young animals stay mobile and survive while their bodies are rapidly changing. We also study how primates move through trees, using both field observations and laboratory experiments to understand walking, climbing, and leaping on branches. Our work reveals how animals meet the physical challenges of their environments and how movement has been shaped over development and evolutionary time.