Elephant Poo is a World Class Fertilizer...Sometimes

You can't make an omelette without breaking some eggs...or grow a Torchwood tree without sending it through an elephant's digestive system. Written by guest blogger Jin-Gyu Chang.

Published on 19th January 2026

In the coastal forests of Southern Kenya there lives a species of tree called the Torchwood, Balanites maughamii (not to be confused with the semi-successful Doctor Who spin-off series), that produces a small, dull looking fruit. Bitter-sweet, strong smelling and containing a seed that accounts for more than half of its mass, the fruits of the Torchwood are of no interest to the canopy dwelling animals of the Kenyan forests. They instead drop to the forest floor, often before they are even ripe, to attract a much larger friend to help them disperse: Elephants.

A World of Giants

Elephants fall under a role known as the mega-herbivore. As the name might suggest, these are herbivores that can reach over 1000kg when they are fully grown. Given their size, and the amount of food they need to eat to achieve this, they have significant effects on the world around them. From trampling vegetation, to going where smaller herbivores cannot for fear of being eaten, mega-herbivores could be considered the big dogs of their ecosystems, just like Joe Marler in any given episode of Celebrity Traitors 2025.

One of the important functions that elephants fulfil as megaherbivores is to eat, and then eventually poop out, seeds. Their huge range means they can eat a fruit in the morning of one day, and by the evening of the next its seeds can come out the other end in a completely different location, wrapped in a nice nutritious package of dung. This is a process known as dispersal and is a great way for plants to ensure that they don’t end up competing for resources with their relatives.

African elephants (Loxodonta africana) function as mega-herbivores, consuming large amounts of vegetation that contributes to the dispersal of seeds. Picture taken by Jin-Gyu Chang.

Some plants, such as the Torchwood tree, rely entirely on the appetites of these mega-herbivores for seed dispersal. They have evolved fruits that are well camouflaged but smell irresistible to elephants, with their poor eyesight but great noses. This way, they are not being eaten by other animals, such as antelopes and monkeys, which might damage the seeds or not carry them far enough.

Whilst it may seem like common sense that one of the main advantages of being eaten would be that bonus starter pack of faeces at the end of the ordeal, we shouldn’t always assume what we know is universally true. In this article, published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, Njuguna et al. have performed a simple yet elegant study, and set out to answer not one, but three questions:

- How does distance from the tree affect how many of these seeds get eaten?

- Does getting eaten by elephants actually help these seeds germinate and grow?

- Does elephant poo contribute at all to the germination and growth of the seeds?

A Yummy Snack

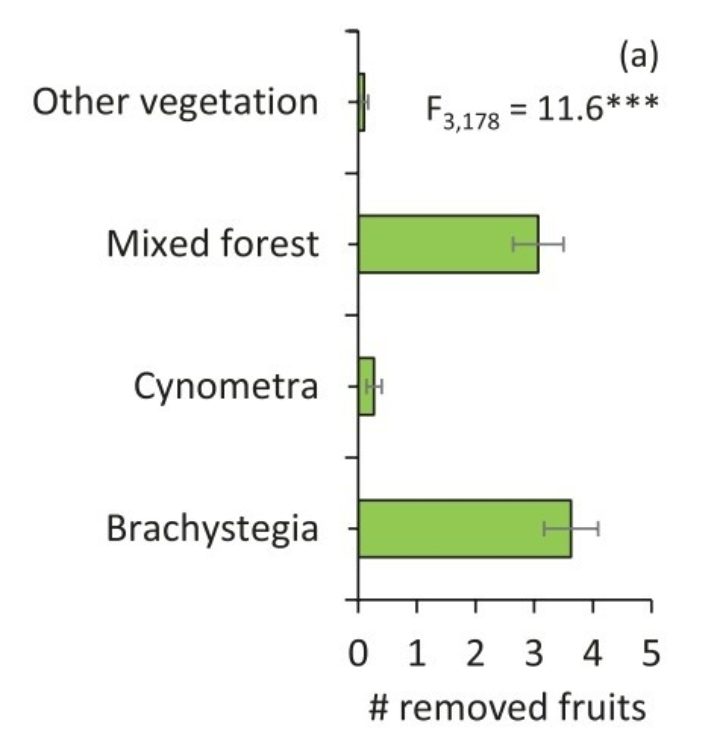

Figure 2: A graph showing the rate of fruit removal in each forest type. The bars represent the mean number of fruits removed.

Let’s start, as most things do, with that first question. Njuguna et al. set out ripe Torchwood fruits at regular intervals from 21 parent trees in various parts of the forest. They spent 36 weeks observing these fruits, recording any instances of the fruits being eaten, such as bite marks, fruits being removed, and local dung. What they found may not be a shock to anyone, but it is important to establish: elephants did indeed eat fruits that have fallen closer to the parent tree than those that fall further away.

Interestingly, the researchers found that rates of seed predation varied significantly with the composition of the forest that the trees were found in. Areas of forest that had more open understories (“Brachystegia” and “Mixed” in Figure 2) that make it easier for the elephants to move around and locate the fruits tended to have higher rates of seeds being eaten.

It’s Not About the Destination, But the Journey

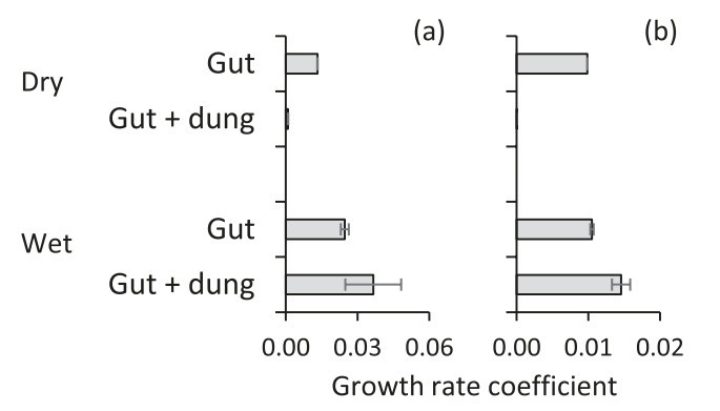

Now onto the findings that may surprise some of you. When measuring the germination rates, final heights and number of leaves of 448 plants, the elephant dung only seemed to help them during the wet season. In fact, during the dry season, the addition of dung slowed the growth rates of germinated plants almost to a halt (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Bar graphs showing the growth rates of plants that germinated after they had been digested by the elephants. They show the growth rate of plant height [A], and the rate at which the number of leaves increased [B].

Why is this? It seems a little strange that the dung would inhibit plant growth, even if it didn’t have any positive effects. It may be to do with the fact that whilst dung does contain a lot of readily available nutrients, it can also contain toxic compounds and harmful bacteria that inhibit plant growth.

The real star of the show here is the elephant’s digestive system itself. The seeds that had been eaten by the elephants all showed greater success in germination than those that had been collected directly from the fruits by the researchers. In fact, during the wet season only the seeds that had been eaten by elephants germinated, whilst in the dry season only 12% of the undigested seeds germinated. The average time taken for seeds to germinate decreased from 96 to 47 days if they were eaten, and the success rate jumped up to 74%.

It seems that during the act of being eaten the seed undergoes many processing steps that ensure success. Firstly, the flesh of the Torchwood fruit contains compounds that prevent premature germination, which is stripped off as the fruit is eaten. Secondly, the outer layer of the Torchwood seed (called the endocarp) is immensely thick and removing this significantly increases the chance the seed will successfully germinate. In fact, it seems that of all the animals in Southern Kenya, only the elephant has teeth that are strong enough to strip the seeds of their tough outer coating, something even other mega-herbivores like buffaloes and rhinos cannot do.

Through this study, Njuguna et al. were able to show the extraordinary role that elephants play within their ecosystems, with entire species being dependent on their continued existence for survival. Losing these magnificent creatures would spell disaster for the world’s biodiversity.

About the Journal

This blog was inspired by a paper published in our Biological Journal, the direct descendant of the oldest biological journal in the world. It publishes ground-breaking research specialising in evolution in the broadest sense, and especially encourages submissions on the impact of contemporary climate change on biodiversity. Want to contribute to a blog? Contact the Journal Officer directly.

Guest Blogger

Jin-Gyu Chang is a Presenter/Producer at the Royal Institution, developing and delivering content for events onsite as well as external events such as Glastonbury Festival. They believe that you don’t have to be a scientist to do science on a day-to-day basis. Their aim is to get people interested in science at a level where they can appreciate how it is in their jobs, hobbies and everyday lives. Edited by Georgia Cowie, Journal Officer at the Linnean Society.