Ghosts of the Past: How DNA Reveals an Extinct Island Lineage

How genome-wide analyses uncovered a hidden extinction event, showing that island colonisation often ends not in success, but in silent disappearance. Written by guest blogger Adam Brachtl.

Published on 3rd November 2025

Islands offer an ideal setting to study evolution in action. Their isolation allows scientists to explore how new species form, a process known as speciation. When a few individuals colonise a new island, they often adapt to its unique conditions and then gradually evolve into a separate species from their mainland relatives. But not all colonisation attempts are successful. Many species fail to establish or eventually disappear, leaving only traces behind in the genetic record. A new study from the Canary Islands, published as part of the Special Issue “Evolution on Islands” in the Evolutionary Journal of the Linnean Society by Emerson, Campedel & Noguerales, uses molecular genetics to uncover these hidden stories.

Weevils of the Canary Islands

Insects are particularly valuable for studying evolution on islands because their diversity, abundance, and often limited ability to disperse make them sensitive indicators of how species form and disappear. Because of their small size and the variety of habitats they occupy, insects often evolve unique lineages even when separated by short distances. The weevils from the Canary Islands offer a unique opportunity to explore these patterns. In this study, researchers examined the Laparocerus tessellatus group (species complex of closely related weevils) to understand how different island populations are related, focusing on Laparocerus auarita from La Palma. Earlier research hinted that this species might have arisen from a mix of colonists from Tenerife and Gran Canaria. Emerson et al. set out the following questions: (i) was L. auarita formed through hybridisation between these two island lineages, or (ii) does an undiscovered second species exist on La Palma?

Using DNA to Reconstruct Evolution

To investigate these questions, more than 200 weevils were collected from three Canary Islands: La Palma, Tenerife, and Gran Canaria. Each island’s populations were sampled from several sites to capture as much genetic variation as possible. The team extracted DNA from each specimen and used modern genomic techniques to analyse thousands of differences across the genome, allowing them to look beyond single genes and compare overall genetic patterns among islands. They focused on two types of genetic information: mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited from the mother and helps trace lineage history, and nuclear DNA, which represents the full genetic makeup of each individual.

To interpret these data, the researchers examined population structure and genetic diversity to see how variation is distributed within and between islands. They also reconstructed phylogenetic relationships to identify how island populations are evolutionarily related, and applied demographic modelling, which tests different historical scenarios such as isolation, colonisation, or hybridisation. By combining these approaches, the team built a detailed picture of how the weevils on each island are related and whether La Palma’s species shows signs of hybridisation.

The Ghost of a Lost Species

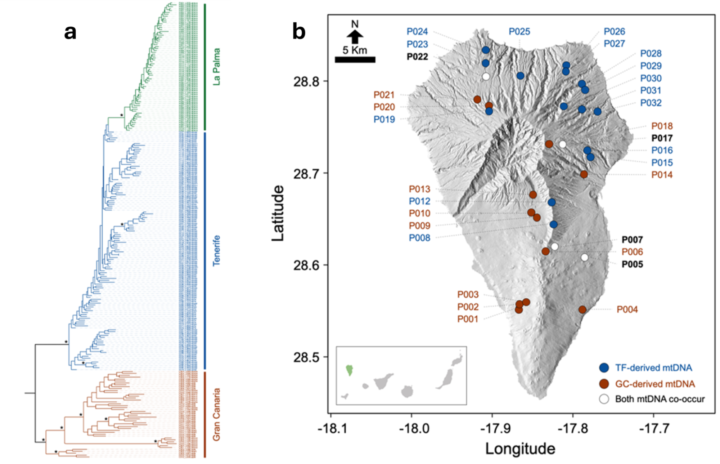

The analyses revealed a clear pattern of colonisation and loss. Nuclear genetic data showed that the La Palma weevil population, Laparocerus auarita, originated from Tenerife, not from Gran Canaria, as once suspected (Figure 1a). The researchers found no evidence of a second, hidden species on La Palma and little sign of hybridisation in the nuclear genome, which reflects overall ancestry. Yet the mitochondrial DNA (inherited through the mothers) told a different story, showing traces of ancestry from both Tenerife and Gran Canaria (Figure 1b). This mismatch suggests that after Tenerife weevils colonised La Palma, a second, short-lived colonisation from Gran Canaria occurred. The two lineages briefly interbred, but the Gran Canaria population eventually disappeared, leaving behind only its mitochondrial signature in the surviving species. The scientists suggest that the already-established Tenerife weevils may have outcompeted the newcomers, but with selection favouring the persistence of the Gran Canaria mitochondrial DNA within La Palma. This work shows how genetic data can reveal the traces of species that no longer exist, offering new insight into the outcomes of island colonisation.

Figure 1. a) Relationships among Laparocerus tessellatus group weevils (Laparocerus auarita belongs to this complex) from La Palma, Tenerife, and Gran Canaria based on nuclear genomic data. b) Map of La Palma showing where Laparocerus auarita weevils were collected. Colours indicate mitochondrial ancestry: blue for Tenerife, brown for Gran Canaria, and white for mixed sites.

Why Does This All Matter?

This research demonstrates how modern genetic tools can reveal extinction events that would otherwise go unnoticed. By using genome-wide data, scientists can detect when a species colonised an island, briefly established, and then disappeared, leaving only genetic traces behind. The findings suggest that colonisation between islands may be more common than previously thought, but success is limited when closely related species are already present. Importantly, this study demonstrates that even short-lived species can leave a lasting mark on the genetic landscape, highlighting the hidden dynamics of island biodiversity. By revealing these “ghost lineages”, studies like this help us better understand how colonisation, hybridisation, and extinction together shape the diverse and fragile ecosystems of islands.

About the Authors

Brent Emerson is an evolutionary biologist based in the Canary Islands, who seeks to exploit features of islands and their invertebrate fauna to address questions of general interest that span the fields of evolution and ecology. He is particularly interested in understanding how species traits, particularly dispersal ability and niche, interact with topoclimatic variation to influence spatial patterns of diversity, from the spatial structuring of genes within species through to patterns of community assembly.

Víctor Noguerales is an evolutionary biologist interested in understanding the mechanisms shaping patterns of biological diversity. The integration of genomic, phenotypic, and ecological data with spatial and demographic modelling is paramount for the development of his research. This approach allows him to understand the consequences of changing environments on genomic variation across different levels of biological organization (population, species, communities), while providing evidence-based knowledge that can be integrated into the conservation agendas facing global change.

Alya Campedel participated in the research as a visiting research student from the Ecole Normale Supérieure de Paris, where she was studying toward and interdisciplinary Masters in Life Sciences.

Guest Blogger

Written by Adam Brachtl (pictured), a recent graduate of Queen Mary University of London, where he completed a master’s degree in Bioinformatics. He is interested in how genomics, genetics, and epigenetics influence the evolution and adaptation of species, and in using bioinformatics to explore these processes. He is currently pursuing a PhD in this field. Edited by Georgia Cowie, Journal Officer at the Linnean Society.

This blog was inspired by a paper in the "Evolution on Islands: From Genomes to Communities" special issue. Want to contribute to a blog? Email the Journal Officer directly.