Fathers Out Of The Blue: Leatherback Turtles Take a DNA Test

Discover how DNA detective work is revealing the secret love lives of leatherback turtles–and reshaping how we protect this critically endangered species.

Published on 2nd September 2025

What really goes on when sea turtles mate in the open ocean? Thanks to a bit of genetic investigation, scientists are starting to find out–and the truth is a lot more dramatic than anyone expected.

Who's Your Daddy?

Leatherback turtles are wide-ranging ocean travellers with soft, leathery shells. Despite their vast geographical distribution, they're now considered 'Critically Endangered' by the IUCN due to fishing bycatch, habitat loss, and climate change.

Studying the romantic lives of leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) is a bit like trying to piece together someone’s dating history without ever witnessing a date. These elusive reptiles mate far offshore, leaving almost no clues about who’s mating with whom. Yet, with leatherbacks facing mounting threats from human activity and climate change, understanding how they reproduce is key to protecting them. A new study from Brazil published in the Biological Journal of the Linnean Societyhas shed light on their secretive love lives, uncovering unexpected twists and turns that rival the drama of a wildlife soap opera.

The Trouble with Turtle Love

Leatherback turtles are mysterious by nature. The largest of all sea turtle species, they spend their lives crossing entire oceans, only visiting land to lay eggs. While females come ashore to nest, males rarely, if ever, return to land–making their mating patterns particularly tricky to study.

To uncover the mystery, Bispo et al. turned to genetics. Using microsatellite DNA markers, specific sequences within an organism's DNA that vary from individual to individual (think of them as genetic fingerprints), the team compared the DNA of mothers and their hatchlings to figure out just how many males contributed to each nest. This study represents the first application of this technique to Brazil's leatherback population and revealed a previously undocumented mating system characterised by high levels of multiple paternity.

Polyandry and Polygyny

The study examined 15 leatherback turtle nests from Espírito Santo, Brazil, using DNA collected from over 200 hatchlings. The results were rather interesting, uncovering that 60 % of the nests were sired by more than one male–a behaviour known as polyandry. This is the highest rate ever recorded for this species, surpassing previously reported polyandry rates in Leatherback populations around the world, such as 41.7 % in the St. Croix population!

Interestingly, whilst polyandry benefits males by increasing the chances of passing on their genes, it doesn't appear to help females much. There's no clear evidence suggesting that multiple mates improve hatchling success or offspring viability. What’s more, since the researchers only sampled a portion of each clutch it's likely the actual number of fathers involved is even higher than reported, making this sea turtle mating system even more complex than it appears on the surface.

In sea turtles, polyandry means one female mates with multiple males–so a single nest of eggs can have more than one father. Polygyny is the reverse: one male mates with multiple females, fathering hatchlings in more than one nest.

But wait, there's more. Of the identified males, 41 % fathered hatchlings in multiple nests, marking the first documented case of polygyny in leatherbacks. In other words, some ambitious males weren't just sticking with one partner; they were making the rounds, fertilising clutches from several different females. From a population point of view, this could be a good thing. Multiple paternity can boost fertilisation success, improve hatchling survival, and increase genetic diversity–all of which are critical for a species trying to survive in a rapidly changing world.

Once again, for the males it's a win-win: more offspring, more genetic legacy, and relatively little effort or risk. But for the females? Not so much. Mating with multiple partners means increased exposure to predators, a higher risk of disease, and energy loss in fending off persistent suitors. It's a high-cost strategy that may offer few direct benefits–raising important questions about how much of this behaviour is driven by choice versus pressure?

Does Size Matter? Apparently, Yes

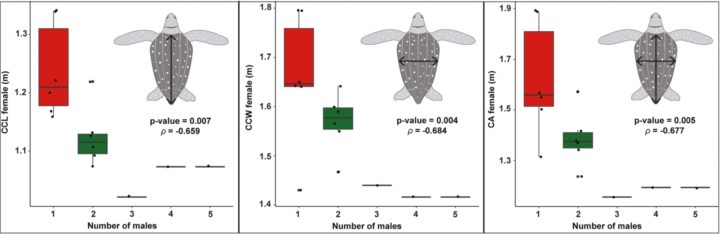

Another interesting discovery made by Bispo et al. was that there is a clear pattern between female size and number of mates. By measuring the curved length and width of the turtles’ shells (known as the carapace), researchers found that larger females tended to have fewer mates, while smaller females were associated with up to five different fathers per clutch.

Why? In this scenario, multiple mating by female sea turtles could be a form of damage control; females attempting to make the best of an undesirable situation in response to male harassment. Larger females may be better equipped to avoid or resist harassment, therefore opting for quality over quantity in their mate selection.

Relationship between female carapace size and the number of males contributing to leatherback turtle nests, as measured by curved carapace length (CCL), curved carapace width (CCW), and carapace area (CA). The boxplot colours represent different numbers of males contributing to each nest. Statistical values (P-values and Pearson’s correlation) are provided for each measurement, showing a significant negative correlation between female size and the number of males. From Bispo et al. 2025.

Sperm wars in the South Atlantic

The team also observed signs of sperm competition, where sperm from different males battle it out to fertilise eggs. In some nests, one male's DNA dominated; in others, multiple males had equal shares. This suggests that timing, sperm quality, or even sperm storage could affect who ends up fathering the young.

Another twist? No male was found to contribute sperm across two consecutive nesting seasons, a surprising discovery considering some males are thought to return yearly to breeding grounds. However, with only two years of data, it's too early to draw firm conclusions.

Why does it matter?

Why is turtle romance worth all this effort? The answer lies in genetic diversity. For critically endangered species like leatherbacks, having a broad genetic pool is vital to their survival in the face of climate change, pollution, and habitat loss.

Understanding how these animals mate helps scientists protect their nesting beaches, track male movements, and design better conservation plans. For example, knowing that males may come from distant feeding grounds suggests the need for international cooperation, safeguarding populations across their entire migratory range.

Sea turtles (like those pictured) mate in the open ocean, making it difficult for researchers to know the paternity of hatchlings. Research like that of Bispo et al. is therefore crucial to aid our understanding.

Love Lives with Life-or-Death Stakes

Although leatherback turtles have a long legacy of being mysterious creatures of the sea, we're finally getting a glimpse into their secretive social lives thanks to some clever DNA detective work! Turns out they're far more complex (and promiscuous) than we previously imagined.

Yet this research isn't just about uncovering their romantic adventures. It offers a crucial piece of the puzzle in how we protect a species on the brink. With threats multiplying and time running short, insights like these give conservationists the tools they need to act smarter–and hopefully, help leatherbacks to continue gliding through the seas for generations to come.

About the Paper

This blog was inspired by a paper published in our Biological Journal, the direct descendant of the oldest biological journal in the world. It publishes ground-breaking research specialising in evolution in the broadest sense, and especially encourages submissions on the impact of contemporary climate change on biodiversity. Want to contribute to a blog? Contact the Journal Officer directly.

Guest Blogger

Written by Kateryna Kolesnykova (pictured), a recent graduate of Queen Mary University of London, where she completed a master’s degree in Biodiversity and Conservation. She now works for the Woodland Trust. Her scientific interests primarily focus on the evolutionary history of dinosaurian and pterosaurian species; however, she plans to transition into entomology. Edited by Georgia Cowie, Journal Officer at the Linnean Society.