Seeing Double – Henry and Edward Doubleday – Entomologists

Glenn Benson our Hon. Curator of Artefacts looks at the men behind the images of the Doubledays in the collection of the Society and discovers an unexpected connection to the Victoria & Albert Museum in London where he works.

Published on 16th July 2025

The Epping Naturalists

Figure 1: Henry Doubleday, daguerreotype, c.1863, unknown photographer, donated to the Society by Robert Mays (provenance Thomas and Edith Doubleday). Ref: C30039.

Henry Doubleday (1808-75) and brother Edward Doubleday FLS (1810-49) were born to Quaker parents. Their childhood was spent exploring the “Cockney Paradise” of Epping Forest - 2,400 hectares of woodland and heath that stretches from east London into the neighbouring English county of Essex where the Doubledays lived. This early exposure to nature played its part in their life-long interests in the natural world.

Henry contributed to publications such as The Entomologist and The Zoologist, both edited by his close friend and fellow entomologist Edward Newman FLS (1801-76). He was a lifelong member of the Entomological Society of London (founded 1833, and now the Royal Entomological Society). Said to be an excellent shot and taxidermist, he provided specimens to William Yarrell FLS (1784-1856) for his History of British Birds (1837–43).

Figure 2: Edward Doubleday, by Thomas Herbert Maguire, c. 1850, printed by M & N Hanhart. Presented to the Society by George Ransome FLS (1811-76). From a series of 60 scientific portraits by Maguire privately commissioned by Ransome, in connection with the foundation of the Ipswich Museum (opened 1847). Ref: IP/A&B17.

Where Henry was a “home bird”, Edward liked to explore further afield. In April 1837 he and Robert Foster (dates unknown) landed in New York, they would spend the next two years exploring the United States of America together. Basing himself at the Moore Inn in Trenton Falls in upstate New York, it was here that Edward started to collect moths in earnest. He wandered the woods at night with a lantern but found the mosquitoes “most annoying”, so he placed lights in the windows of the tavern to attract the night flying moths to him.

He would write about his natural history discoveries in The Entomological Magazine (published 1832-38), under the title: “Communications on the Natural History of North America”. Having been turned down for the 1841 expedition to the Niger River, in 1842 he joined the staff of the British Museum (Natural History), now London’s Natural History Museum, as a curator in the Zoological Branch, where he would work for the rest of his short life establishing one of the most comprehensive butterfly collections at that time.

I have only scratched the surface of the lives of the brothers here, a fuller account of Henry’s life, and to some extent Edward’s, is given in Robert Mays's book: Henry Doubleday – The Epping Naturalist, and the 1889 biography of Henry by Miller Christy FLS (1861-1928). It was while reading Robert’s book I discovered Henry’s collection of Lepidoptera was displayed at the Bethnal Green Museum (BGM). Now called Young V&A, it is a branch of the Victoria & Albert Museum (V&A) that displays collections relating to children, childhood and toys. The original Bethnal Green Museum opened in East London in 1872, and until 1920, displayed a mix of art, science, geology, natural history, and animal products.

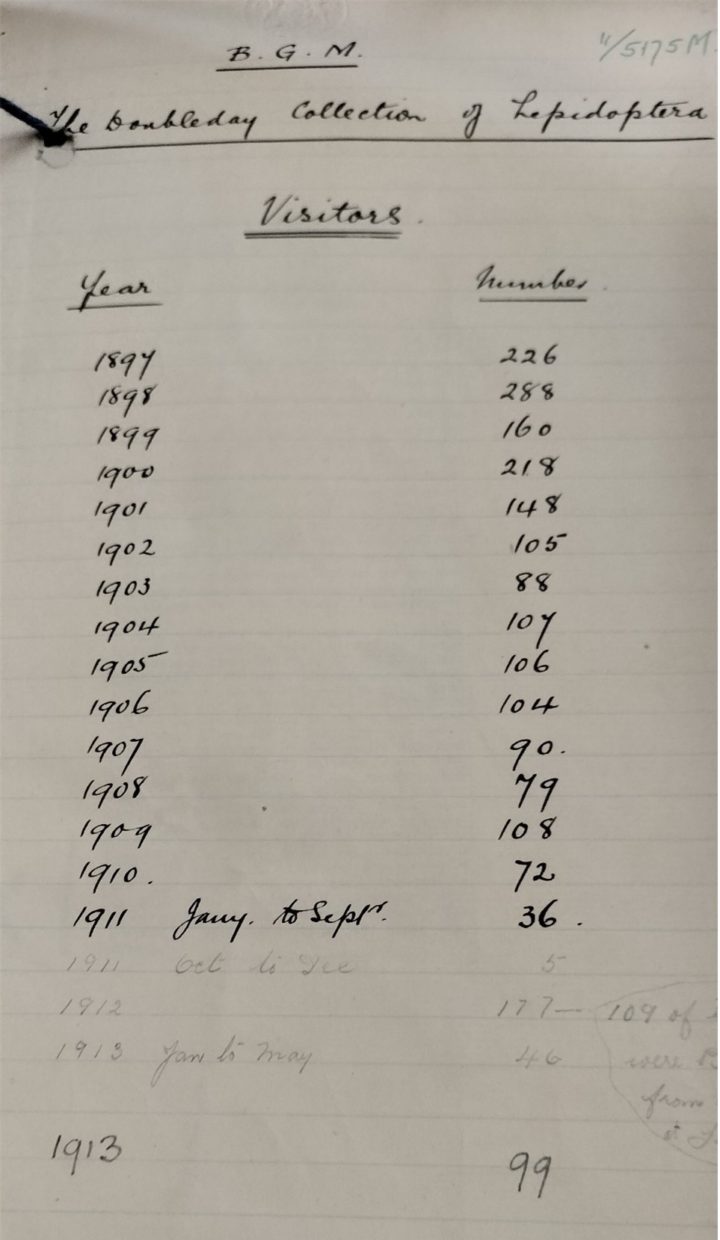

Figure 3: Annotated page from the V&A's copy of the 1877 catalogue of Doubleday's Lepidoptera V&A archive ref: MA/2/B16.

Added to this eclectic mix in 1876 was ‘Mr Doubleday’s Collections of Lepidoptera’. A catalogue of the collection by Andrew Dickson Murray FLS (1812-78) and Albert Brydes Farn (1841-1921) was published in 1877: Details - Catalogue of the Doubleday collection of Lepidoptera - Biodiversity Heritage Library. Doubleday’s collection was later transferred to the Natural History Museum, South Kensington, where it remains. It and other material relating to both brothers can be accessed via the Natural History Museum website: Collections | Natural History Museum.

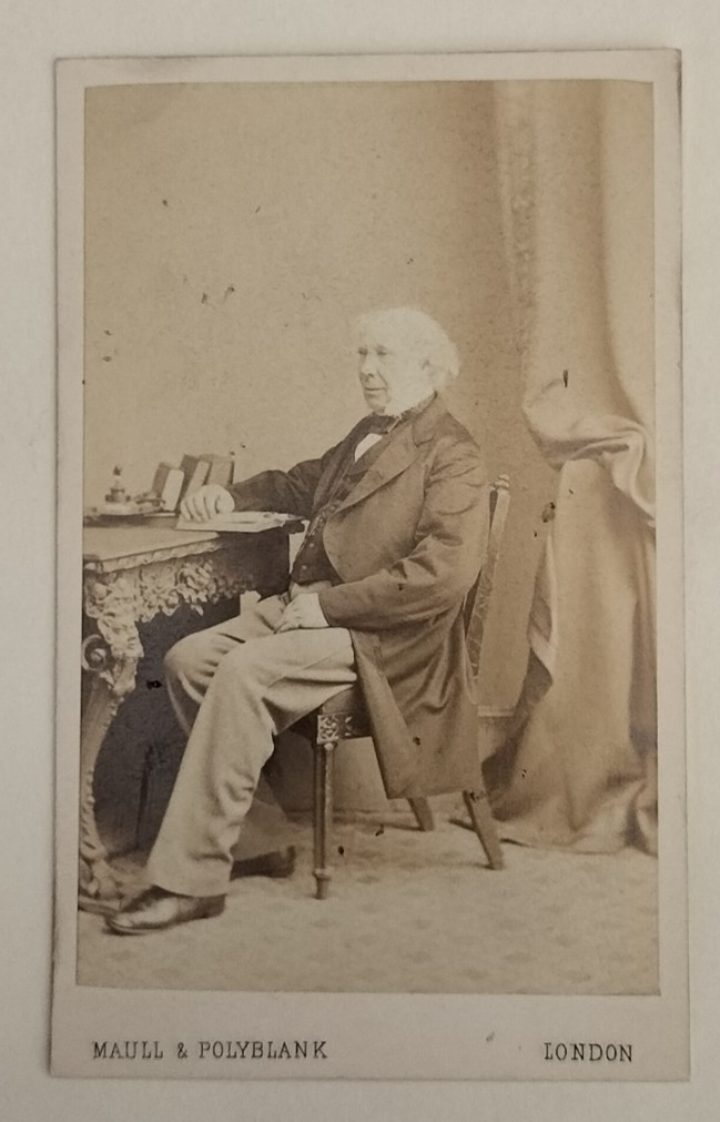

Figure 4: Document recording the number of visitors who viewed Henry Doubleday’s Lepidoptera collection at the Bethnal Green Museum between 1897 and 1913, unknown authors, V&A archive ref: MA/2/B16.

In the archives of the V&A are papers relating to the loan of Doubleday’s collection to Bethnal Green Museum and one piece of paper caught my eye (Figure 4). Those of us who work in the arts, heritage and scientific communities are often called upon to produce data for the benefit of our paymasters, governing bodies or the Government of the day often to justify our existence, to seek funding or demonstrate our public benefit. It seems it was no different in 1913. Correspondence in the V&A’s archive records the discussions that were had at the time as to the future of the Doubleday collections remaining at the Bethnal Green Museum. At some point a member of the V&A’s staff was tasked with logging how many visitors the collection had had while at the museum, I assume to measure its “worth”, usefulness or popularity and this data played its part in determining the future of the collection.

Figure 5: Edward Doubleday (1798-1882), surgeon, photograph in LSL. Ref: PP/D/11.

The name Doubleday is perhaps more familiar to some of us today as the American publishers founded in 1897 by Frank Nelson Doubleday (1862–1934) (no relation to Henry or Edward as far as I can tell). To others the name Doubleday is associated with organic gardening through the Henry Doubleday Foundation. Founded in 1954 it was named after Henry Doubleday of Coggeshall (1810 – 1902), cousin of entomologists Henry and Edward, and is now known as Garden Organic. The fascinating life of horticulturalist Henry Doubleday is told by Coggeshall Museum on their website: Henry Doubleday - Coggeshall Museum. To make things even more confusing Edward Doubleday FLS (1798 - 1882), (no relation as far as I can tell) was a surgeon at the Royal Infirmary for Children, Medical Attendant to St Saviour's Union Workhouse, and Medical Examiner to the Medical Invalid and General Assurance Society.

It’s not surprising then that by the end of all of this I was experiencing diplopia, or should that be quinlopia? Thanks go as ever to the collections team at The Linnean Society of London for their help, advice and patience, and to my sister Vanessa who helped untangle the genealogy of the many Doubledays.

If you want to know what a daguerreotype is, this video made by the V&A explains the process: https://youtu.be/DAPgdo5H7ZY?feature=shared.

Sources

The Great Lakes Entomologist The Genus Phragmatobia in North America, with the Description of a New Species (Lepidoptera: Arctiidae)

All images taken by the author.