Species Plantarum at 270

Carl Linnaeus' catalogue of plant species, "Species plantarum", was published in 1753 and changed the course of botanical nomenclature. In this blog, we uncover the many unique and wonderful copies held in libraries across the world.

Published on 6th September 2023

No two copies of a rare book are the same. What makes each copy unique can be its binding, the annotations left by previous owners, its known ownership, remnants and traces of pressed plants, and many other details. To celebrate the 270 years since the publication of Carl Linnaeus' Species plantarum, partners of the Linnaeus Link Union Catalogue have collaborated to showcase copies of the first (1753) and second (1762-63) editions of Species plantarum held in their libraries.

What is the Linnaeus Link Union Catalogue?

In 1933, the second edition of Basil Harrington Soulsby's (1864-1933) Catalogue of the Works of Linnaeuswas published, shortly after Soulsby's death.

Soulsby, a librarian at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London, assigned numbers to each book, edition, translation, altered edition and each journal article by Linnaeus, and his Catalogue played a key role in standardising the cataloguing of the major Linnaean collections. In the late 20th century, the Linnaeus Link Union Catalogue was set up to continue Soulsby's work in the age of the internet. Initially co-funded by the NHM and Linnean Society, LLUC brings together all records from its partners' libraries, and allocates Post-Soulsby Numbers. These Soulsby numbers act as key indicators in the cataloguing process and are used to enable the identification of the holding locations of the titles through the Catalogue - a significant scholarly resource and education tool which is coordinated by the Linnean Society.

Today, LLUC is managed and funded by the Linnean Society and boasts 20 partners, who meet once a year.

The significance of "Species plantarum"

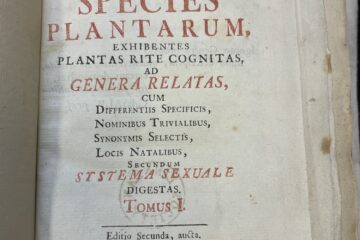

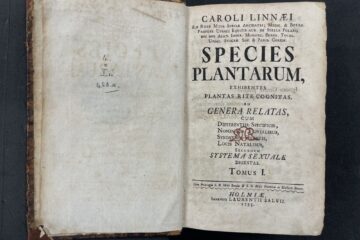

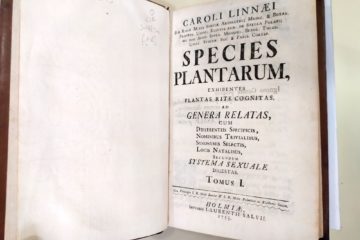

Species plantarum, Latin for "The Species of Plants", aimed to list all genera and species of plants known in Europe, classified according to Linnaeus' famous sexual system. Begun in the 1740s, it was a true labour of love for Linnaeus, which left him exhausted and overworked. After its publication by the Stockholm based printer Laurentius Salvius, he called it 'the fruit of the most and best part of my life'.

Species plantarum is the first work to consistently apply binomial names and is still used today as the starting point for the naming of plants. In the late eighteenth- and early nineteenth century, the second edition was considered more important than the first one, and many "botanists used it as the standard edition: that is, most of their references in plant-descriptions and on flower-plates are to the revised, enlarged, more common form of the book. Only in this century has there been international agreements to use the first edition as the basic edition for nomenclature” (Allan Stevenson, Catalogue of botanical books in the collection of Rachel McMaster Miller Hunt. Pittsburgh, Hunt Botanical Library, 1958-1961, vol.2, part 2, p. 250).

As the starting point for naming most plants, Species plantarum is still invaluable to work of botanists and scientists today.

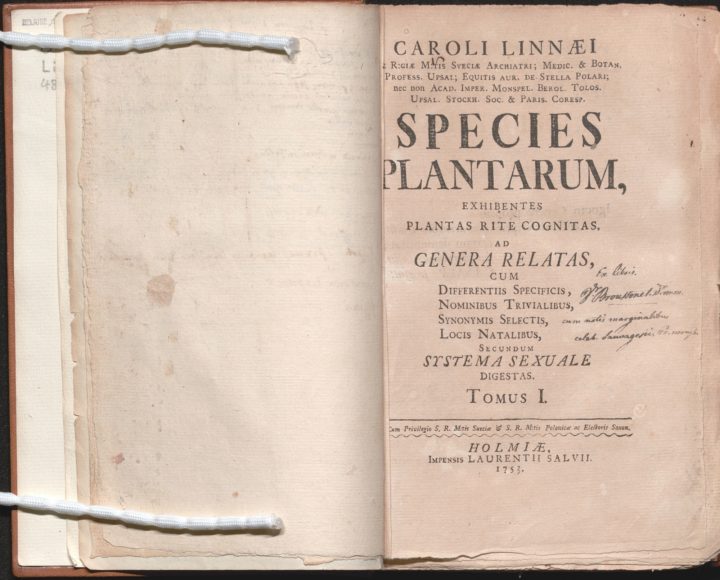

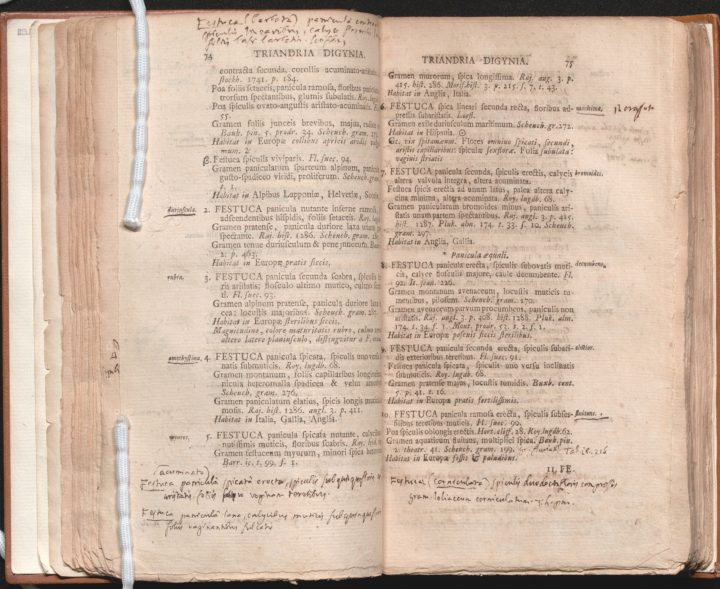

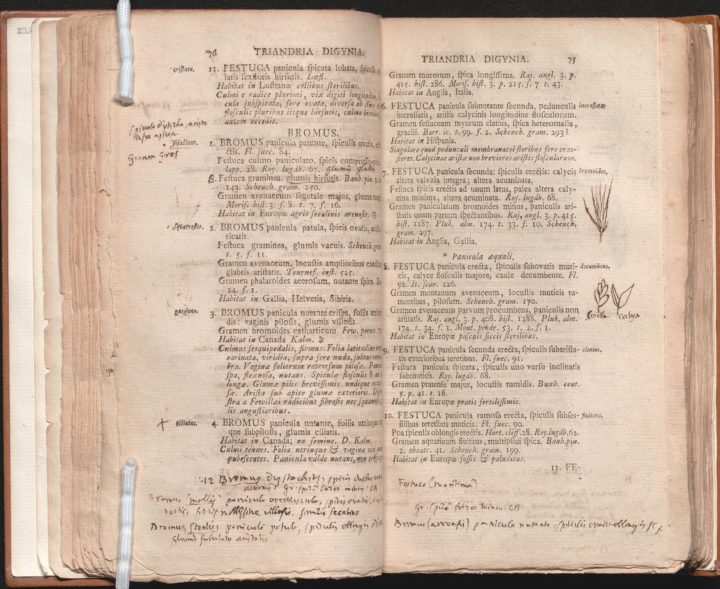

Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de Genève, Switzerland

The Geneva copy contains the extremely rare first version - together with its definitive version - of pages 75, 76, 89, 90, 259 and 260. Linné had these pages recomposed during the printing process and the first version should have been destroyed. This book was also owned by François Boissier de La Croix de Sauvages (1706-1767), a botanist from Montpellier, who corresponded with Linné. This botanist has annotated the margins at length. The copy still bears the ownership mark of the Montpellier physician Jean-Louis-Victor Broussonet (1771-1846), brother of the botanist and zoologist Auguste Broussonet (1761-1807). The latter was Augustin-Pyramus de Candolle's predecessor as director of the Montpellier Botanical Gardens.

Pierre Boillat, Bibliothécaire principal, Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques de Genève

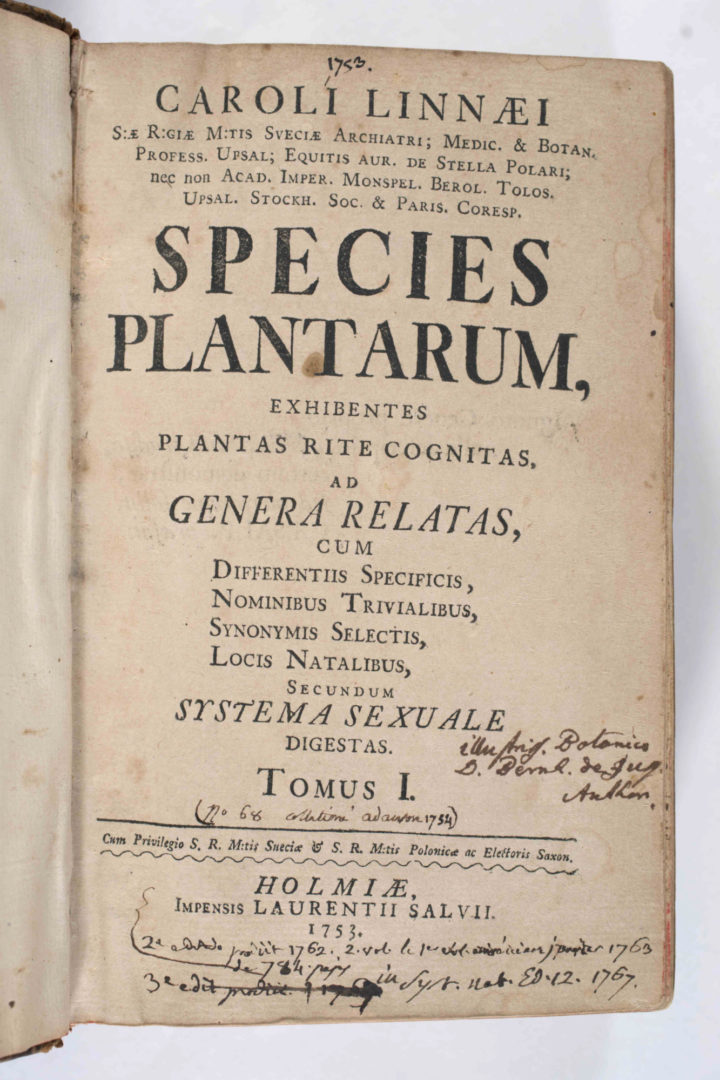

Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, United States

In 1961-1962 Roy A. Hunt purchased Michel Adanson’s (1727-1806) botanical library for Hunt Botanical Library (now Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation) at Carnegie Mellon University. It includes the copy of Species plantarum that Adanson received from his professor and mentor Bernard de Jussieu (1699-1777), who had received it from Carl Linnaeus, inscribed by Linnaeus to Jussieu. Adanson intensively annotated this copy, now digitized at https://www.huntbotanical.org/library/show.php?1 (scroll down for finding aid; select AD85).

Library reference: AD85

Chuck Tancin, FLS, Librarian, Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation

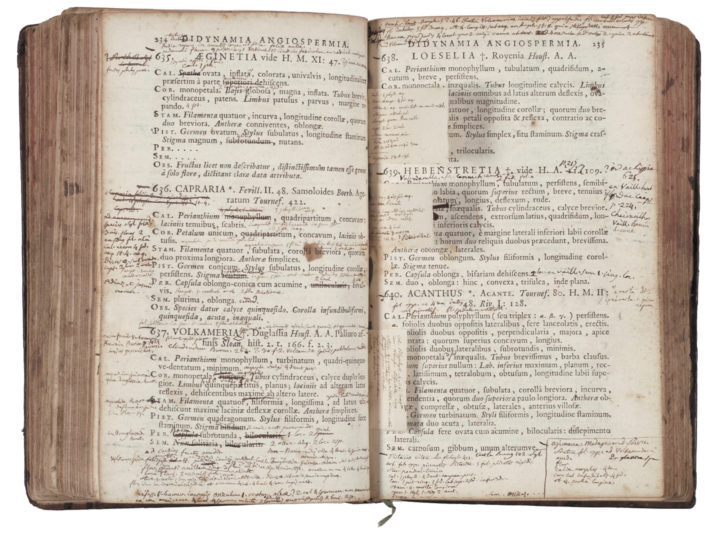

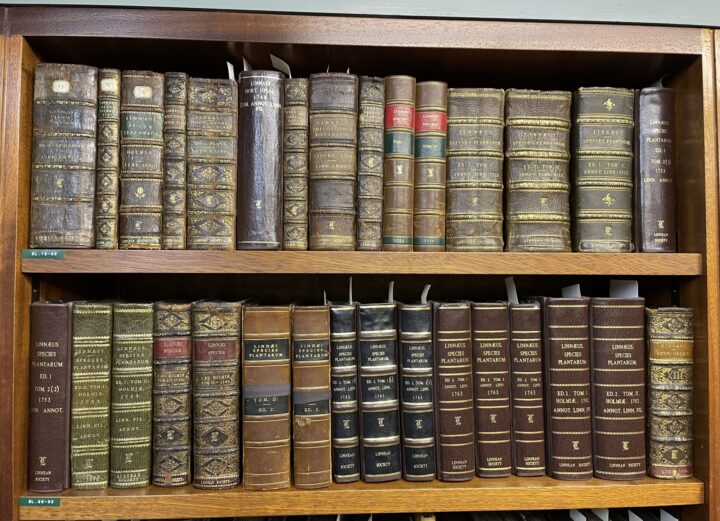

The Linnean Society of London, UK

Copies of Species plantarum in the Linnaean collections of the Linnean Society.

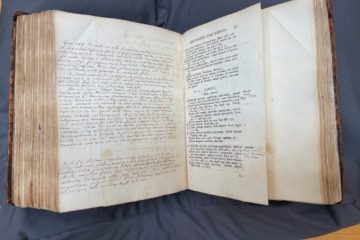

The Linnean Society is lucky to hold no less than four copies of the 1753 first edition, and four copies of the 1762-63 second edition, all from the Linnaean collections. Four copies are interleaved and have Linnaeus' heavy annotations. Linnaeus used copies of his work as physical platforms on which he prepared the next edition - in a way very similar to Track Changes on Microsoft Word today. Having copies of his own works interleaved allowed him more space to annotate his work, but means some copies needed to be bound in more volumes than the original two. Many of the changes in the second edition can be traced back to annotations in the 1753 copies, allowing a glimpse of Linnaeus' working methods and thought processes.

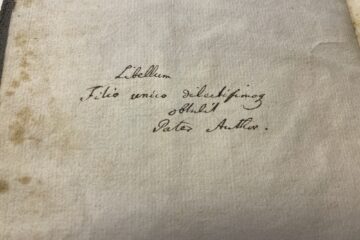

In addition to Linnaeus' own copies, a copy of each edition belonged to Linnaeus' son, also called Carl Linnaeus - the Younger to distinguish him from his father. Linnaeus dedicated a copy of the 1753 edition to his son: 'The father and author presented this little book to his only beloved son'. Carl Linnaeus the Younger was 12 at the time. A copy of the 1762 edition is also annotated by Linnaeus the Younger.

More copies of Species plantarum can be found in the Library, including an interleaved and annotated copy of the second edition by the English botanist Thomas Martyn (1735-1825).

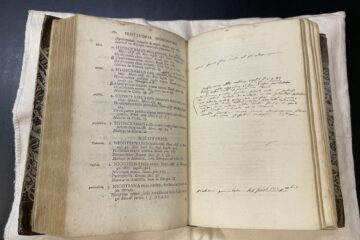

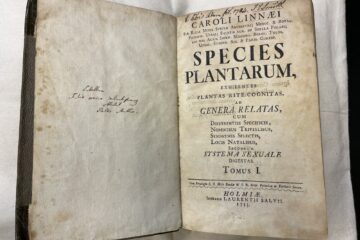

The images in the gallery below show:

- Species plantarum 1753, BL.83: spines of the two volumes, interleaved and annotated copy, opened at the page for the genus Nicotiana, tobacco (Linnaeus was a heavy smoker);

- Species plantarum 1753, BL.85: copy dedicated by Linnaeus to his son. Title page and dedication;

- Species plantarum 1762, BL.86: title page. All of Linnaeus' books were inscribed by James Edward Smith, purchaser of the Linnaean collections in 1784 and founder of the Linnean Society;

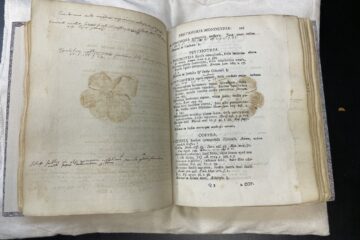

- Species plantarum 1762, BL.88: interleaved and annotated copy, opened at the page for the genus Coffea, coffee (Linnaeus considered that coffee was good for you and a bracing drink as long as it was taken in moderation and not too near bedtime). It bears the imprint of a pressed flower.

- Species plantarum 1762, L.IV.753 (762): interleaved and annotated copy, belonging to Thomas Martyn, opened at the page for the genus Linum, flax.

Isabelle Charmantier, Head of Collections, Linnean Society

Natural History Museum, London, UK

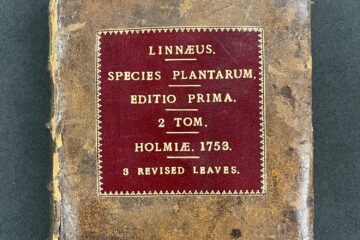

1753, first edition

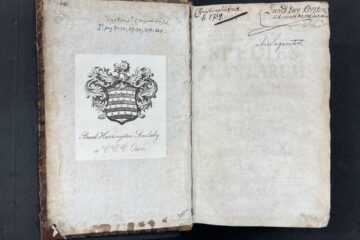

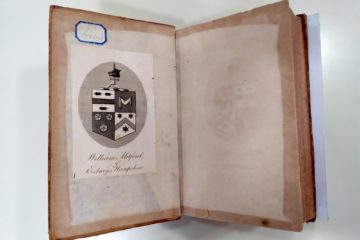

This first edition of Species plantarum is from the Linnean rare books collection preserved at the Library and Archives of the Natural History Museum and is the copy which belonged to Basil Harrington Soulsby (1864-1933) who worked as a librarian at the Museum from 1909 until his retirement in 1930. As seen in the introduction, Soulsby's Catalogue of the Works of Linnaeus (1933) is now the basis for the Linnaeus Link Union Catalogue. The volume bears his bookplate alongside other provenance information.

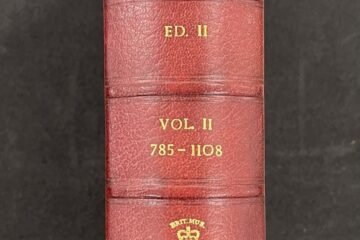

1762-63, second edition

This second edition of Species plantarum is understood to be the Swedish botanist Daniel Carlsson Solander’s copy which he took with him when he travelled on the Endeavour voyage (1768-1771) with Captain James Cook and Joseph Banks.

During the voyage, Solander (1733-1782) and Banks (1743-1820) collected 30,382 specimens including more than 360 described species. An apostle of Linnaeus, Solander travelled to England in 1760 to promote the new Linnean system of classification as set out in Species plantarum while also working at the British Museum cataloguing the collections from 1763 until he departed on HMS Endeavour in 1768.

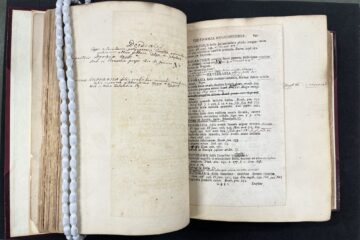

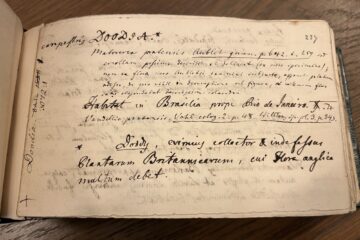

This copy, which has since been rebound for conservation purposes, was interleaved by Solander and is full of annotations and new plant descriptions. Seen last in the image gallery is the annotated interleaved page which has the inclusion of Doodia and the corresponding manuscript slip of paper that Solander created copious numbers of which contained the descriptions of the plants they collected. He then systematically arranged them in the Linnean system - a task he was able to accomplish with the aid of his copy of Linnaeus’s Species plantarum.

The images in the gallery below show:

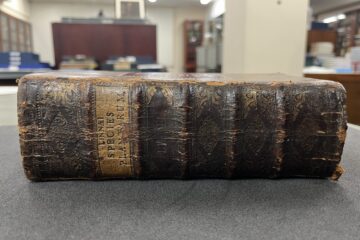

- Soulsby's copy of the 1753 Species plantarum, L 4 o Li 480a: spine, cover, bookplate and title page;

- Solander's copy of the 1762/3 Species plantarum,B SB LIN 582 109-114: spine, annotations and interleaf, opened at the page for Doodia;

- Solander slip pages for the genus Doodia, MSS BANKS COL SOL.

Andrea Hart, FLS, Library Special Collections Manager, The Natural History Museum

Plantentuin Meise, Belgium

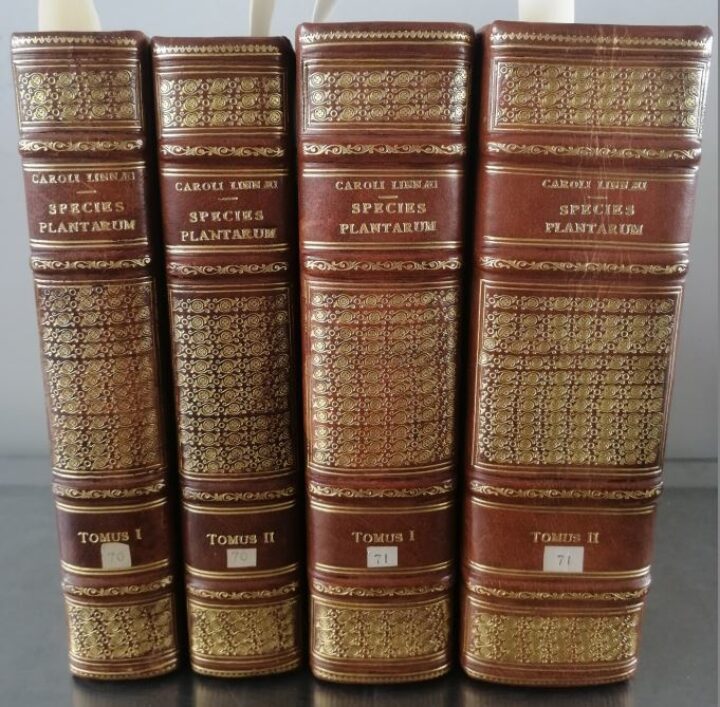

Copies kept at Meise Botanic Garden of the first and second editions of Species Plantarum. Both came from the 1868 Benoni Verhelst auction. Note that the bindings of both editions are identical.

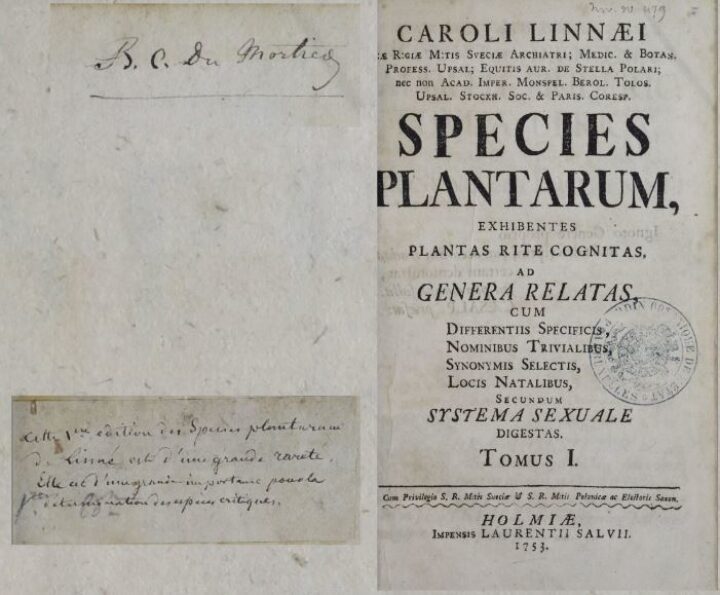

The copy of the first edition of Linnaeus’ Species plantarum (1753) preserved at Meise Botanic Garden is quite common and seems of little interest. Its only distinctive feature is a handwritten inscription on a cover page: "Ex bibliotheca B.C. Du Mortier".

Barthélemy Charles Dumortier (1797-1878) was a Belgian botanist and statesman who played an important role in the creation of the Jardin botanique de l’Etat in Brussels in 1870. An admirer of the Swedish botanist's work, Dumortier started a collection of Linnaeus’ publications in 1818, which he expanded throughout his life. In 1827, he also travelled to England to consult the illustrious botanist's herbarium.

However, it wasn't until 1868, when the library of Ghent art collector Benoni Verhelst was dispersed, that the Belgian statesman acquired the first edition of Species plantarum, 50 years after the start of his collection. In the copy preserved in Meise, an unsigned handwritten note states that "Cette édition du Species plantarum de Linné est d’une grande rareté. Elle est d’une grande importance pour la détermination des espèces critiques".

Two letters from Dumortier to François Crépin, then Professor of Botany at a horticultural school near Ghent and future Director of the Botanic Garden founded two years later, highlight the acquisition of this work.

In the first letter, incorrectly dated April 14, 1864 [read 1868], Dumortier asked Crépin to attend the Benoni Verhelst public auction, which was scheduled a few days later, on April 20, 1868, to buy two publications by Linnaeus: the first edition of Systema naturae and the first edition of Species plantarum. These two works, which he described as "more curious than useful", would complete his "rich collection of Linnaeus’ publications". He gives his correspondent the price he is prepared to pay for each of the two books, adding that the first edition of Species plantarum is "without specific names and therefore without use" - an assessment that may seem odd to a 21st century reader but that illustrates the debate regarding the taxonomic and nomenclatural values of both editions highlighted in the introduction. He takes advantage of his letter to recommend to Crépin three fundamental works by Linnaeus offered at the same auction, stating that in his opinion these works are indispensable in a botanist's library. These were the 13th edition of Systema naturae, Vienna, 1767-1770 (Soulsby 116), the second edition of Species plantarum, Stockholm, 1762 (Soulsby 500), which Dumortier described as "the usual good edition", and Mantissa plantarum, Stockholm 1767 & 1771 (Soulsby 311 & 312).

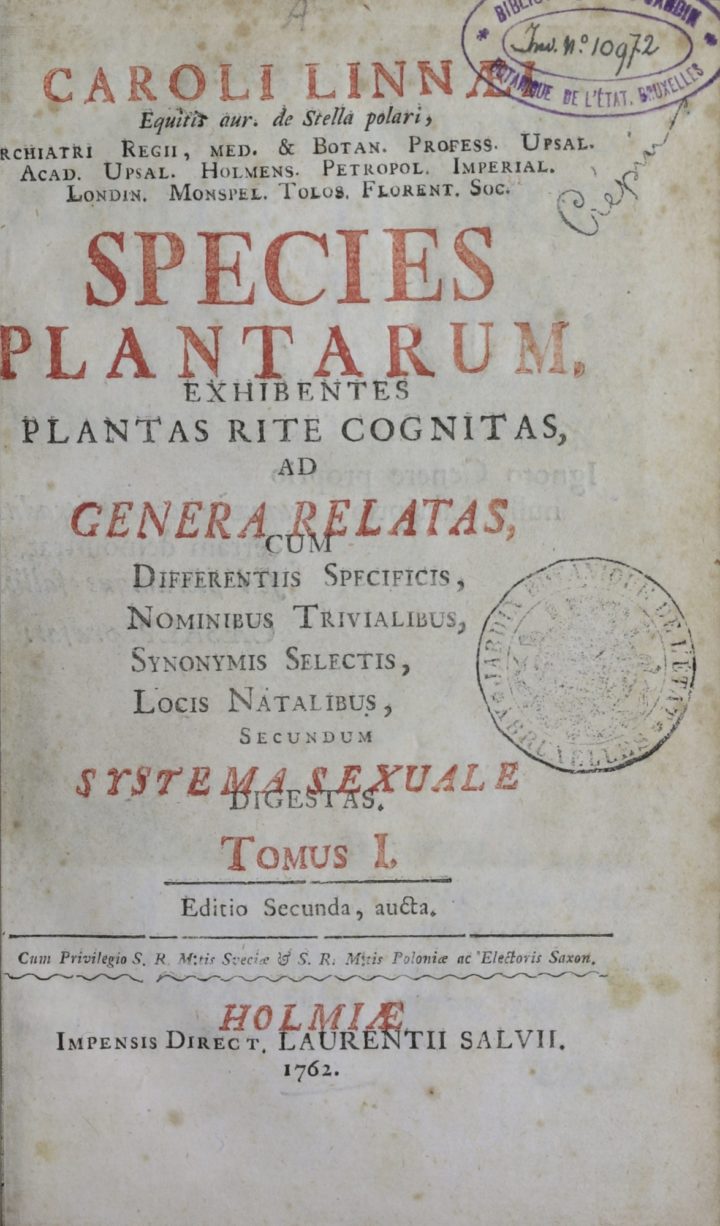

In the second letter, dated April 26, 1868, Dumortier thanked Crépin for purchasing Species Plantarum for him, the copy of Systema naturae having passed him by. He also congratulates Crépin on his own purchases. It is therefore likely that Crépin bought the second edition of Species plantarum recommended by Dumortier. Indeed, the copy of this edition, preserved in Meise, bears Crépin's stamp.

As for the other two works mentioned by Dumortier: The copy of Systema naturae 1767-1770 also bears a note indicating Crépin’s ownership, probably the copy purchased at the same Benoni Verhelst auction. However, the copy of Mantissa plantarum preserved at Meise Botanic Garden does not bear Crépin's ex libris.

To summarize and complete this note: of the four editions of Species plantarum preserved at Botanic Garden Meise:

- The first (Stockholm 1753; Soulsby 480) comes from the collections of Barthélémy Dumortier (copy purchased at the auction of the Benoni Verhelst collection);

- The second (Stockholm 1762-1763; Soulsby 500) comes from the library of François Crépin (copy purchased at the Benoni Verhelst auction);

- The third (Vienna 1764; Soulsby 510) comes from the library of the Société royale d'horticulture de Belgique, precursor of the Jardin botanique de l'Etat in Brussels;

- The fourth (Berlin 1797-1825; Soulsby 512) comes from the collections of Barthélémy Dumortier.

Nicole Hanquart, Head of Library, Art and Archives, Meise Botanic Garden

Real Jardín Botánico de Madrid, Spain

1753, first edition

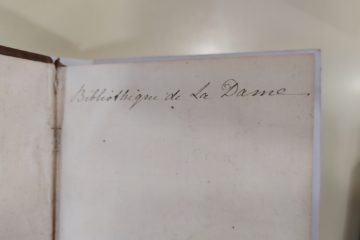

In 2015, the Library of the Madrid Royal Botanic Garden, RJB-CSIC, acquired a copy of the first edition of Species plantarum. Until that date our library had no original copy of that edition. We have not yet been able to find out who was the mysterious lady to whom this copy belonged to (see handwritten annotation on the end paper: “Bibliothèque de la Dame”).

1762-63, second edition

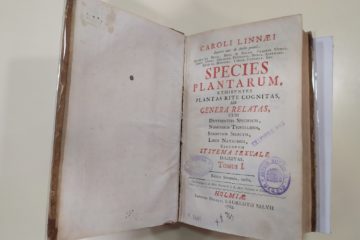

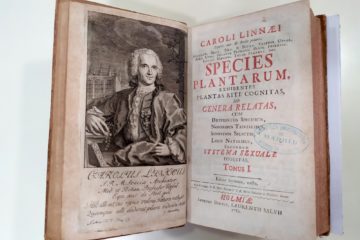

RJB-CSIC is also fortunate to hold two copies of the second edition of Linnaeus' Species plantarum (1762-63). One of them belonged to William Mitford (1744-1827), English Member of Parliament and historian, and includes a portrait of Linnaeus.

Images in the gallery below show:

- 1753 edition of Species plantarum: title page and endpaper;

- 1762 edition of Species plantarum: title page, with portrait of Linnaeus, William Mitford's ex libris.

Félix Alonso Sánchez, Head of Library, Madrid Royal Botanic Garden

Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh, UK

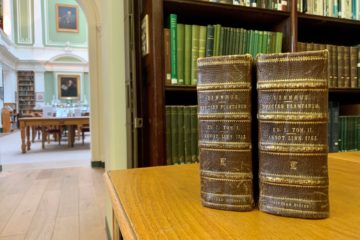

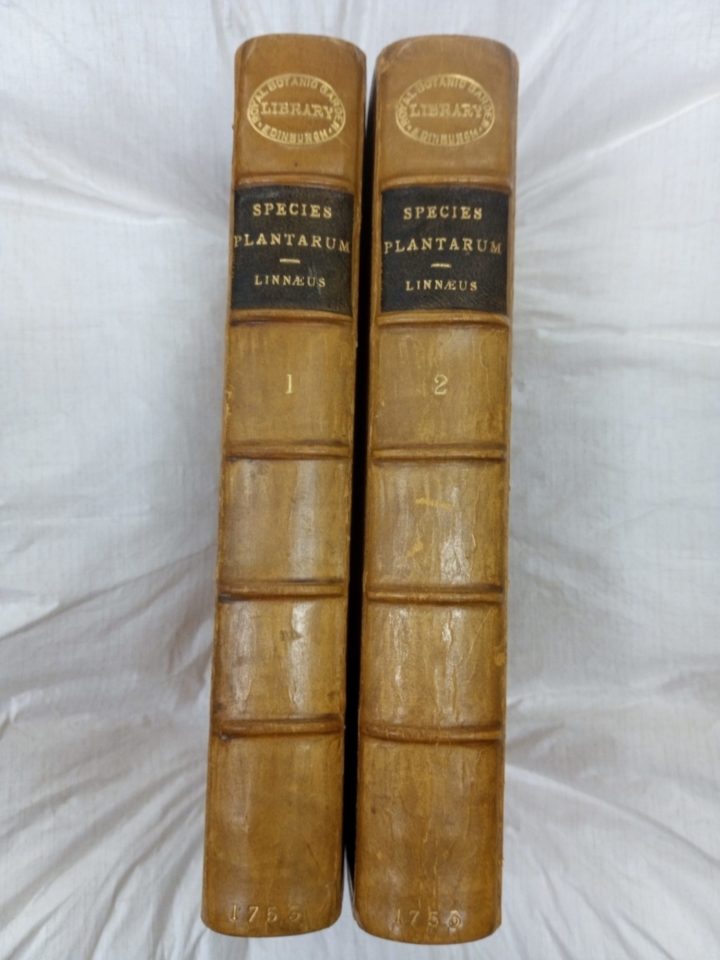

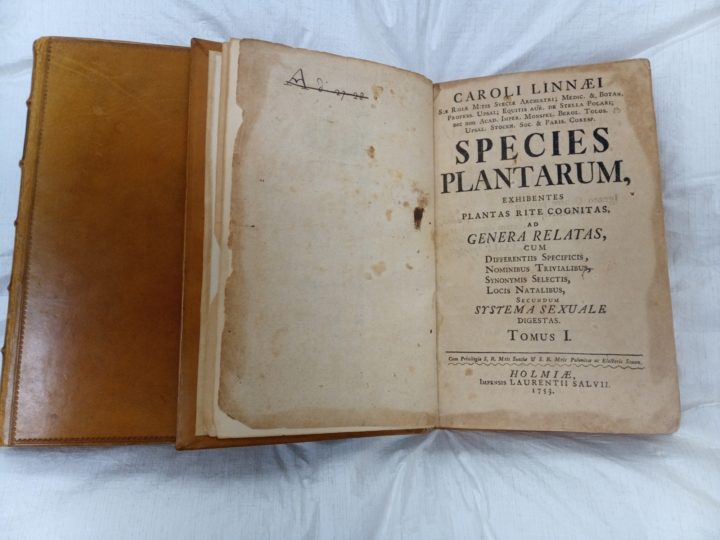

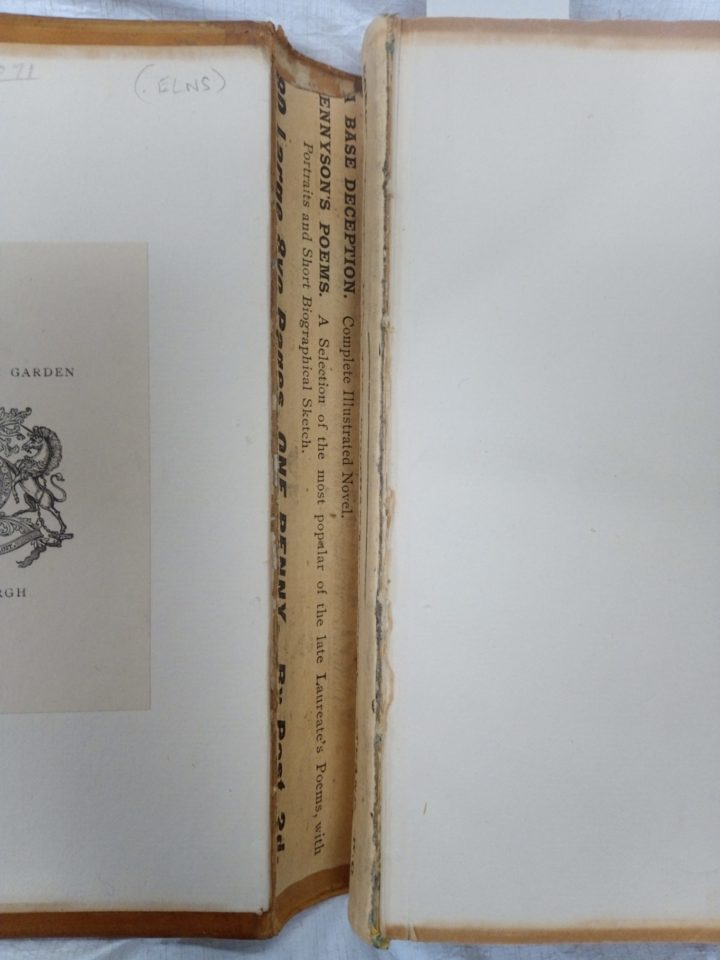

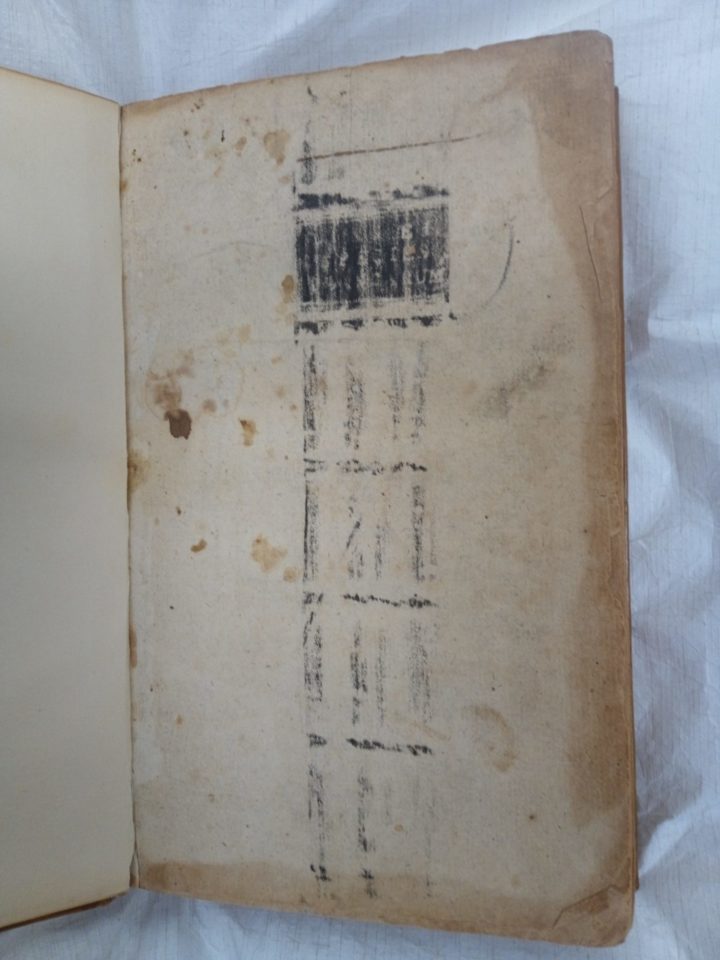

RBGE's two volumes of 1753 Species plantarum

The Library at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh (RBGE) holds Scotland’s national collection of botanical and horticultural literature which includes one copy of the first edition of Species plantarum. Bound in two volumes, little is known of the book’s provenance other than a shelf mark in manuscript in an eighteenth-century hand on the verso of the flyleaf of vol. 1. The book was rebound in the 19th century (the front board of vol. 2 is detached and nineteenth-century printer's waste can be seen in the lining); a crayon rubbing of the original spine (title: Linnaei Species Plantarum) is bound on the recto of the original flyleaf of vol. 1.

Lorna Mitchell, Head of Library and Archives, Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh

University Uppsala Library, Sweden

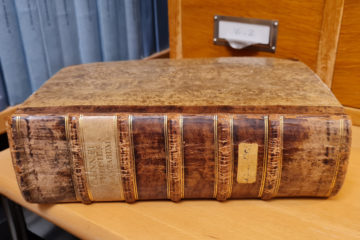

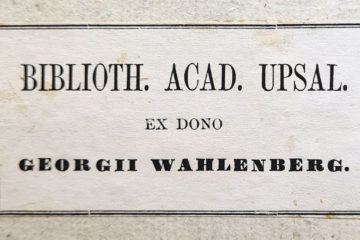

One of the copies of Species plantarum, published in 1753, at Uppsala University Library was donated as part of the book collection of Swedish naturalist Göran Wahlenberg (1780-1851), also known as Georg. He was a student in medicine in Uppsala, appointed botanices demonstator in 1814 and professor of medicine and botany in Uppsala in 1829, succeeding Carl Peter Thunberg. Wahlenberg was thus the last holder of the undivided chair that had been held by Linnaeus. On the inside of the front cover we find a printed bookplate specially made for the books in this donation. There are no marks of owners before Wahlenberg.

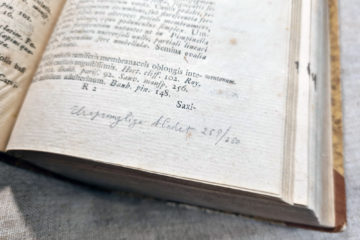

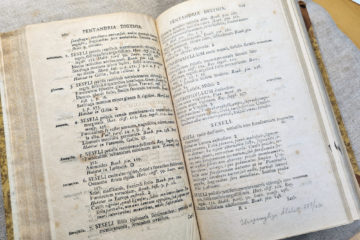

The volume contains the two parts bound together in a half leather binding with brown marbled book paper and sprinkled edges. It has only a few added notes in pencil in the margin. However, it also contains two printed versions of the pages 259/260, one with an added note by former librarian at Uppsala University Library Markus Hulth (1865-1928). He claims that one of this particular folio is the original version. For that reason, Hulth also claims that the volume is a rarity.

Images in the gallery below show:

- 1753 Species plantarum, Uppsala University Library, Sv. Linnésaml. 146: spine, ex libris, pp. 259-260 with Hulth's annotations;

- Portrait of Göran Wahlenberg, Uppsala University Library, Sv. Port.saml. Vanl. f.

Helena Backman, Librarian, Uppsala University Library