Finding the Original Collectors of Linnaeus' Fishes

In 1771, a black man braved a storm to collect a fish that was sent to Linnaeus and is studied even today. Head of Collections Dr Isabelle Charmantier uncovers the invaluable role of unrecognised black collectors employed by Alexander Garden.

Published on 9th October 2022

Content warning: the following blog contains descriptions and terminology which are outdated and offensive. Such terminology does not reflect the current views and values of the Linnean Society.

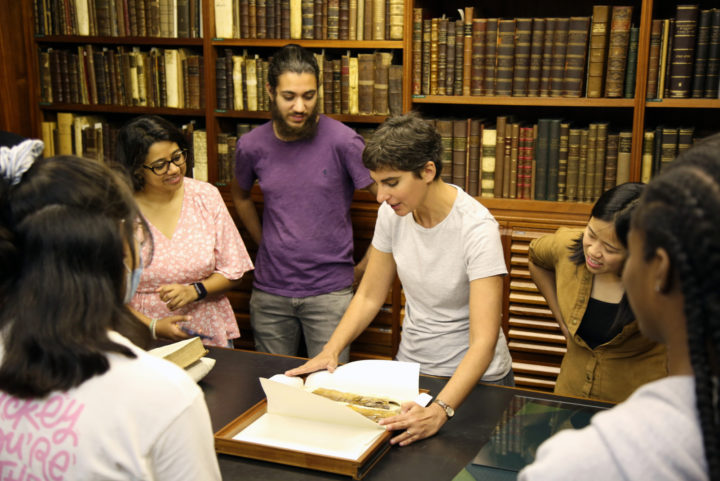

During tours of the Linnean Society, my colleagues and I show visitors the collections of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778), the 18th century naturalist, whose books, manuscripts, and specimens of plants, fish, shells and insects, were bought in 1784 by the founder of the Linnean Society James Edward Smith.

The visitors are always awed by the collections, but the biggest gasps of surprise always erupt when the fish specimens are unveiled. This is because these are pressed or dried fish, kept much like the pressed plants in Linnaeus’ herbarium. The loudest gasps are usually reserved for the seahorses, and for the long ladyfish that was cut in two so that it fits on the sheet of paper.

Unveiling the ladyfish during a tour.

Ladyfish, Elops saurus, LINN 90

Alexander Garden: from plants to fishes

The collection of fishes in the Linnaean collections comprises 168 specimens. The major part of the collection was sent by Alexander Garden (1730-1791), a Scottish physician, to Carl Linnaeus in Uppsala, Sweden. Garden left his native Scotland for Charleston in South Carolina, in 1752 at the age of 32, and he remained there for 30 years, practicing as a physician. Because, as he wrote, "there is not a living soul who knows the least iota of Natural History" in South Carolina, all of his conversations about natural history were carried out by letters. He wrote to the merchants and naturalists John Ellis (1710-1776) and Peter Collinson (1694-1768) in London, and the naturalist John Bartram (1699-1777) in Philadelphia. From 1759, John Ellis succeeded in establishing a correspondence between Alexander Garden and Carl Linnaeus.

The Swedish naturalist was not so much interested in the plants Garden was offering to send him, but in the fishes of Carolina. In his response to Linnaeus on 2 January 1760, Garden wrote:

Before the receipt of your letter, I had scarcely paid any attention to our fishes; but all your wishes are commands to me, (…) and therefore I immediately set about procuring all the kinds I can.

Garden therefore embarked on collecting insects, snakes and even a turtle, but mostly fishes, for Linnaeus. He sent six consignments to Linnaeus between 1760 and 1771, each containing between 9 and 42 specimens of mostly dried, but also some wet (kept in rum), specimens. Even when the correspondence with Linnaeus was well established, Garden continued sending his parcels and letters to John Ellis, who as intermediary would then send them on to Linnaeus. A parcel could take a good six months to get from Carolina to Sweden, via London.

Garden was a lively writer, and his lengthy letters are full of the practicalities of collecting, naming, numbering and packing specimens, and their shipping in a time of war. They also reveal to whom Garden, a keen botanist, turned to in order to collect and gather knowledge about the fishes of Carolina.

Garden's collectors

Garden was passionate about plants, and undertook several field trips into the Appalachians to collect plants, but his knowledge of fish was much less sound. He therefore relied on two sources, the first one of which were the contemporary printed works of ichthyology, which included John Ray and Francis Willoughby’s Historia Piscium (1686), Peter Artedi’s Ichthyologia (1738), Linnaeus' Systema naturae (1735), and, most importantly, Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (1729-1747). Garden did not think much at all of Catesby’s work.

On 2 January 1760, he wrote to Linnaeus of the ‘inaccuracy and inability of this writer, in describing and delineating natural objects. (…) It is sufficiently evident that his sole object was to make showy figures of the productions of Nature, rather than to give correct and accurate representations. This is rather to invent than to describe.’

Illustration of a mullet in Catesby's Natural History..., compared to the specimen sent by Garden to Linnaeus in 1760, Mugil cephalus, LINN 139. Garden pointed out the absence of a pectoral fin in Catesby's image, and wrote to Ellis: ‘O my good friend, how many blunders and gross misrepresentations have I seen in Catesby! – gross beyond conception!’

Forced to source reliable information and specimens, Garden turned to people who had on-the-ground knowledge: black servants and fishermen. In 1755, responding to Ellis who wanted to know more about corals, Garden had solicited information from black fishermen. He wrote:

I spoke to several of the fishermen, but as yet to no purpose. Most or indeed all of them are negroes, whom I find it impossible to make understand me rightly what I want; add to this their gross ignorance and obstinacy to the greatest degree; so that though I have hired several of them, I could not procure any thing.

In the light of his own ignorance, Garden’s dismissal of the knowledge of the local fishermen seems unfair and unfounded. Garden was after a specific, ‘scientific’ type of information, which the fishermen would not have necessarily aligned with their own knowledge. He continued to be reliant on them for specimens, not having himself much knowledge in ichthyology. Ultimately, it seems his reliance was not misplaced, as other letters mention black servants whom he tasked with finding fishes and preparing them as specimens.

We know that Garden had enslaved men and women, and inoculated his enslaved population during the smallpox epidemic in 1760. It is possible that it is one of these, or perhaps a free black servant, whom he sent to the island of Providence in 1771. Garden described the servant’s trip thus:

During his stay there, he collected and preserved some fishes amongst other things; but, meeting with tempestuous weather in his return, and being, for several days together, in dread of immediate shipwreck, he neglected all his specimens, many of which perished.

Nevertheless, Garden was able to send some of these specimens from Providence island to Linnaeus, some of which (less than 10) are still extant in the Linnean Society collection. Amongst these is a stuffed specimen of a trumpet fish, with only the right side of the head preserved.

Trumpet fish, Aulostomus maculatus, LINN 153

What the letter reveals, without explicitly stating, is that such a trip must have been undertaken by a trusted and trained servant, who knew how to collect fish, which fish to collect, and how to dry and preserve them in a way that would ensure their survival on the trip back. Unfortunately, Garden does not go into such details, not even divulging the name of this trusted servant.

A slightly earlier letter reveals that his servant(s) were indeed trained in the practice of preparing fish into specimens, through skinning, drying, and varnishing. In 1767, Garden wrote to Ellis:

I lately received a large specimen of the Siren, caught by a hook baited with a small fish. I was absent when it was sent me, and my servant killed and skinned it before I came home, otherwise you should have had it in spirits (…). I have sent you the dried skin of this.

The letters and specimens kept at the Linnean Society offer glimpses of Garden’s reliance on black fishermen and servants, who were crucial to the collection of specimens, and probably also to the gathering of natural historical knowledge that was then passed on to John Ellis and Carl Linnaeus. When Linnaeus published species description of these fish in works such as his Systema naturae, he credited Alexander Garden as the collector of these specimens. But Garden was really the collection creator, hardly ever the true collector, and it is time that the real collectors of specimens were recognised. Further research into local archives, such as the South Carolina Historical Society’s, may reveal more in the future. One day, it would be wonderful to be able to put a name to the black servant who braved a storm in 1771, in order to send to Linnaeus fish specimens that biologists continue to study to this day.

References

- GÜNTHER, A. 1899. The President's Anniversary address. Proceedings of the Linnean Society, 1898–99: 15–38.

- BERKELEY, E. & BERKELEY, D. S. 1969. Dr Alexander Garden of Charles Town. Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press.

- LINNAEUS, C, and SMITH, J. E. 1821. A Selection of the Correspondence of Linnaeus and Other Naturalists, From the Original Manuscripts / by Sir James Edward Smith. London: Printed for Longman.

- WHEELER, A. 1985. The Linnaean fish collection in the Linnean Society of London. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, Volume 84, Issue 1, May 1985, Pages 1–76.

- See also the Linnean Lens online event by Ollie Crimmen and Isabelle Charmantier, 'Alexander Garden’s Fishes' (May 2022).