A Family Feud: George Bentham's life and letters

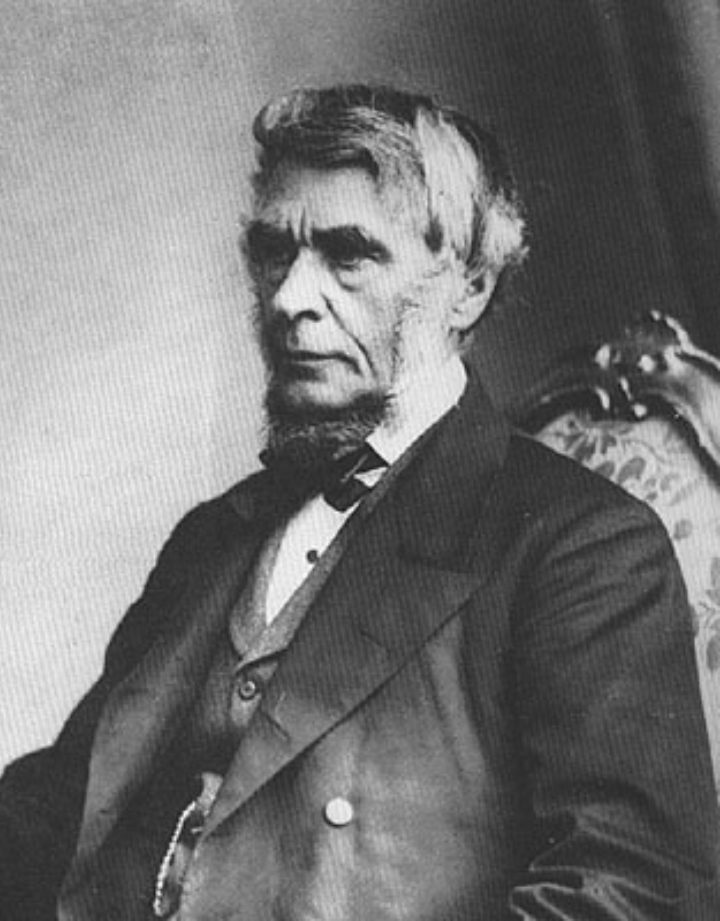

English botanist George Bentham, past President of the Linnean Society, enjoyed a close, bittersweet relationship with his uncle, philosopher and social reformer, Jeremy Bentham, who eventually convinced George to give up the study of law for botany.

Published on 22nd September 2022

Over my internship at the Linnean Society, I have been working with the correspondence of George Bentham (1800–1884), botanist and nephew of Jeremy Bentham (1748–1832), adding name authorities to the archive catalogue to provide further context for the records. The study of George Bentham’s letters and personal journals, I believe, helps us understand the journey and the reasons behind his decision to become a botanist that would one day lead to his election as the president of the Linnean society.

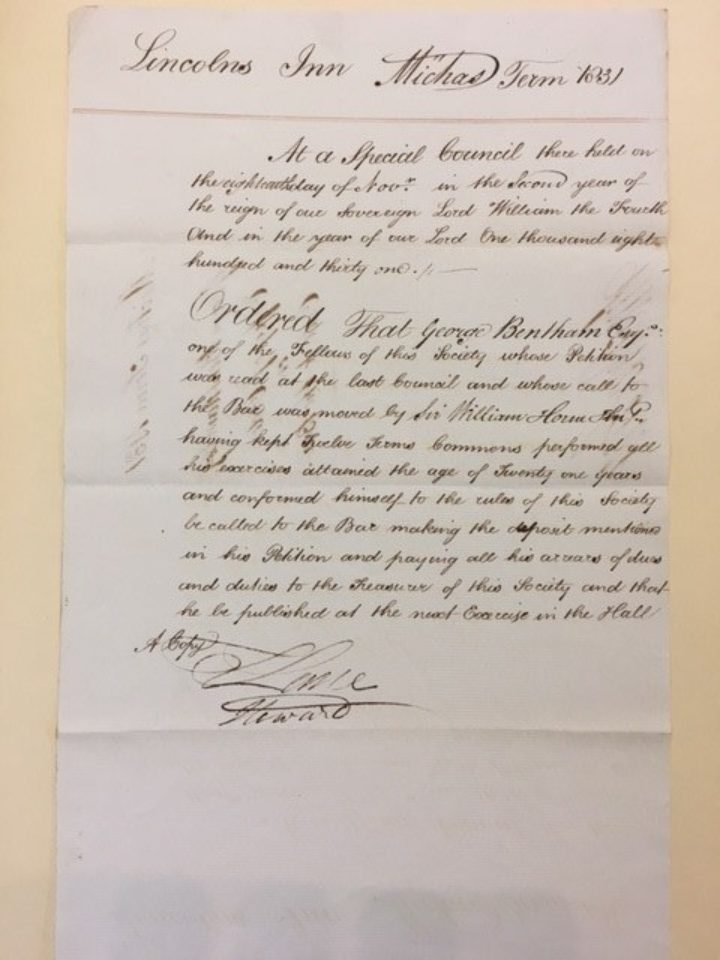

This blog focuses primarily on the years between 1825 and 1833, a decisive period in the life of George Bentham when he started working under his uncle, the philosopher and social reformer, Jeremy Bentham. There were competing demands on George’s time. In addition to his work as an assistant to his uncle, he also acted as an assistant to his father, Samuel Bentham (1757-1831), a naval engineer. He studied Law at Lincoln Inn College. The remainder of his spare time was given over to the pursuit of his growing interest in plants and their classification. The priority given to these competing demands on his time changed throughout this period. At first, George saw botany as a hobby, of secondary importance to his work for his uncle and his studies. However, his botanical endeavours eventually took precedence.

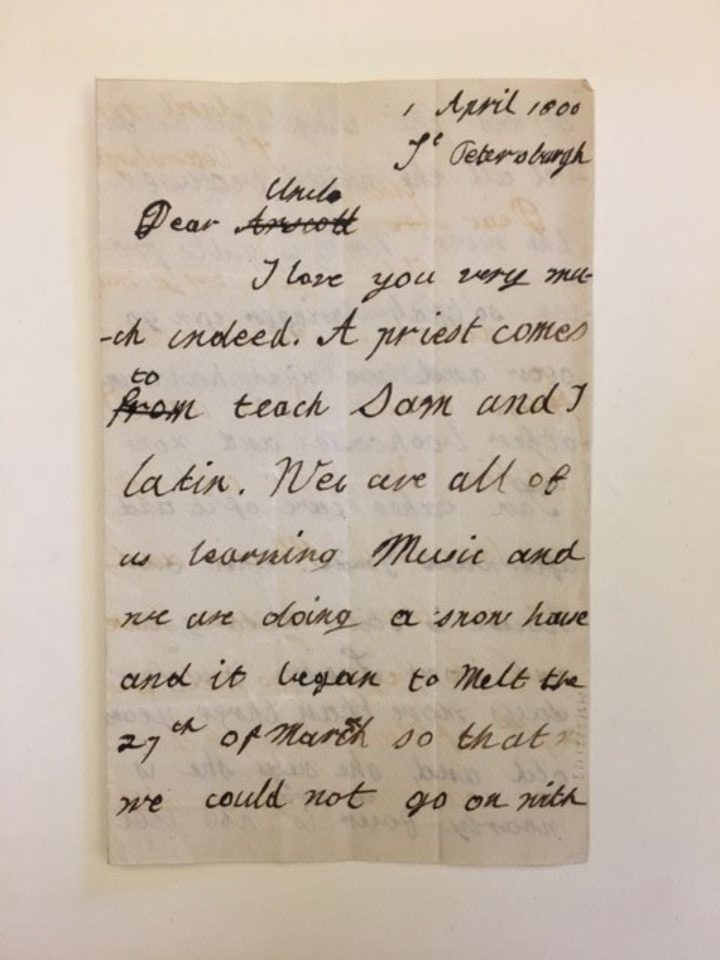

While this relationship between uncle and nephew is not well documented in biographical accounts of the Bentham family, George’s journals and letters, held in the archives of the Linnean Society of London, give a clear account of what his uncle meant to him and how their interactions evolved over time. From his childhood letters, it is clear how greatly esteemed Jeremy Bentham was by his nephew. From age four until Jeremy Bentham’s death in 1832, he was the person to whom most of George’s letters were addressed. In one letter, dated 1st April 1806, George (aged 5) writes to his uncle to tell him the latest news:

“Dear Uncle, I love you very much indeed. A priest comes to teach Sam and I Latin. We are all of us learning Music and we are doing a snow house and it began to melt the 27th of March so that we could not go on with it … the Neva [river in St Petersburg] is not yet began to melt but a little of the snow has.

I am your dear boy, George Bentham”

(MS/322/1/3)

A few months later, on the 18th July 1806, George thanks his uncle for a present and describes his surroundings:

“Dear Sir, I hope you are well. I thank you for the watch that you sent me. We have got little tables and little chairs and presses. Behind the study there is a closet. We have got … books and we have got some wooden rackes.

George Bentham.”

(MS/322/1/5)

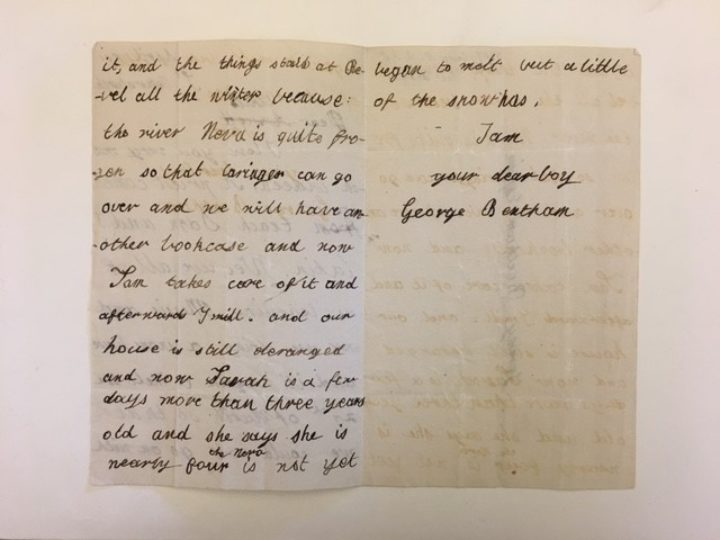

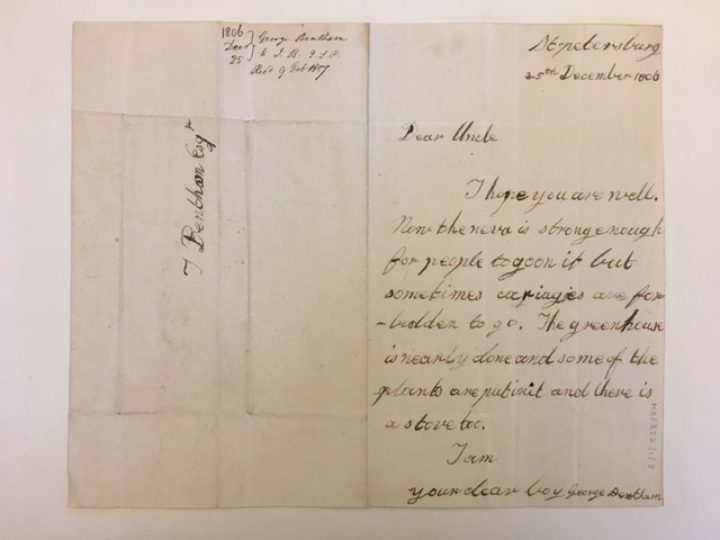

George’s mother, Mary Sophia Bentham, was a botanist. It is no doubt under her influence that, from a young age, George was introduced to the discipline which he would one day pursue, and for which he would become famed. Many of the letters refer to the children’s activities in the garden, as well as the trees and plants for which each child is responsible. On the 25th December 1806, George (aged 6) excitedly outlines the latest developments in the garden in a letter to Jeremy Bentham:

“Dear Uncle, I hope you are well. Now the Neva [river in St Petersburg] is strong enough for people to go on it but sometimes carriages are forbidden to go. The greenhouse is nearly done and some of the plants are put in it and there is a stove too.

I am your dear boy,

George Bentham”

(MS/322/1/8)

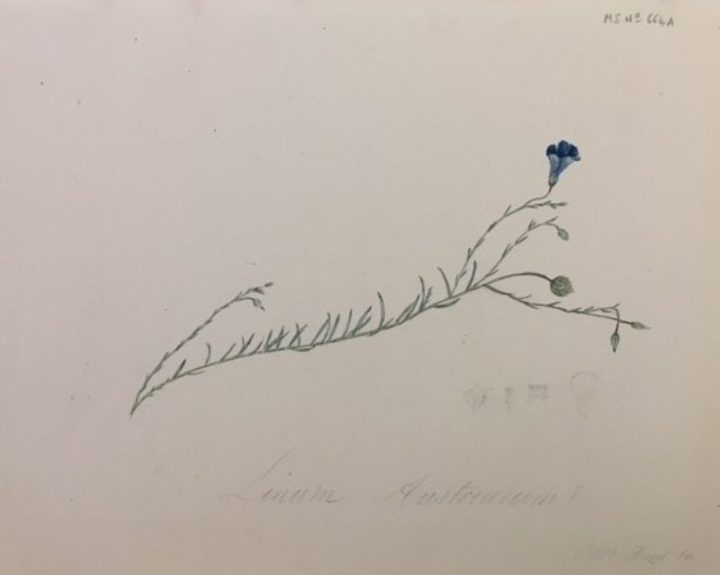

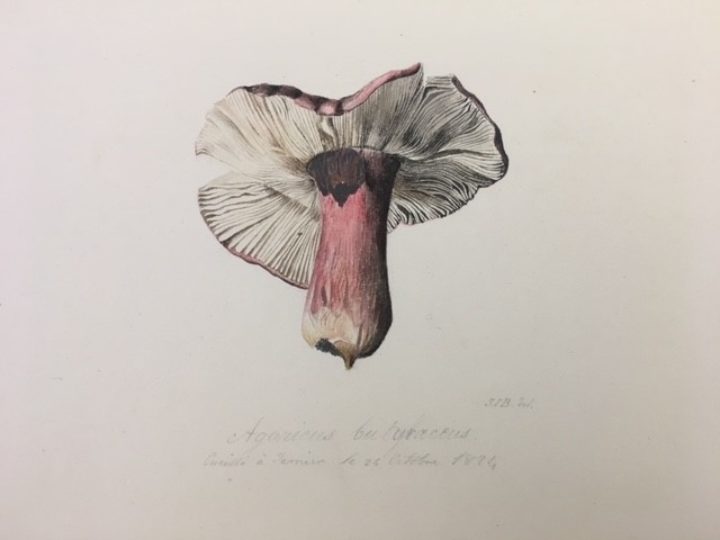

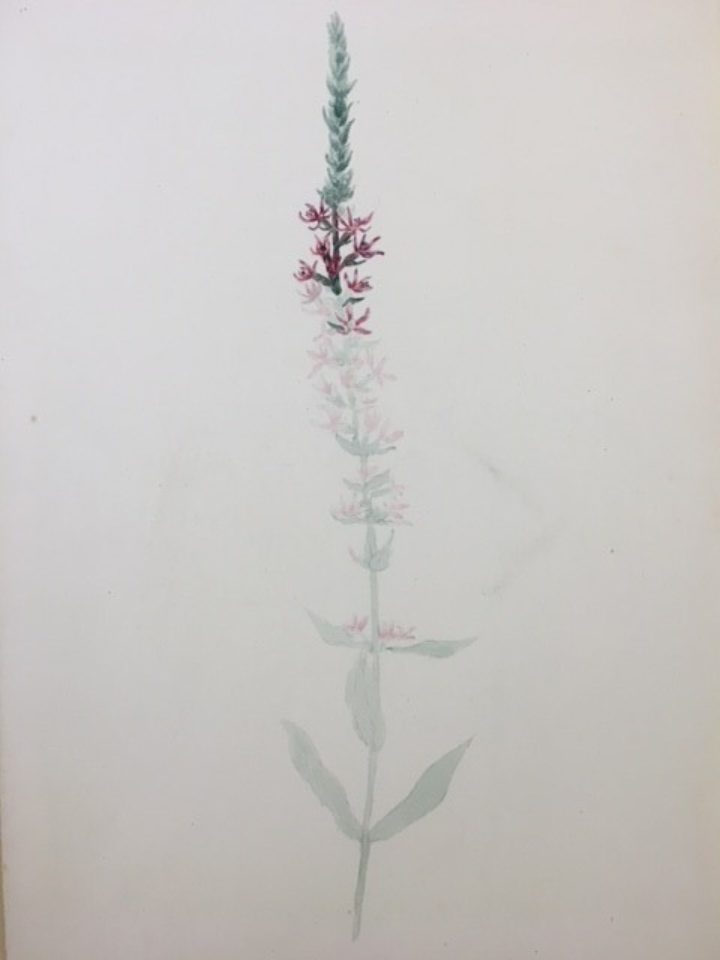

Bentham maintained an interest in botany throughout his life and even made several drawings of plants and fungi, some of which are featured in this blog.

Many other letters addressed to Jeremy Bentham describe the travels undertaken by George and his family. Others describe his interactions with his uncle. Overall, Jeremy Bentham can be seen to have played a generous part in George’s life. By the age of seven, George was already fluent in French, German and Russian. His family later decided to go on a leisurely tour of France. While studying in Angouleme, he came across a copy of Augustin Pyramus de Candolle’s Flore Française, which reinvigorated the interest he had had in botany as a child. In 1825, George reluctantly came back to England and just like his uncle and his grandfather, decided to pursue law studies. His misgivings about the return to England were expressed in a letter to his father:

“Hitherto I have been accustomed to consider myself as destined to become a Frenchman and I have not sufficiently thought of the necessity of keeping up English connexions but now I see too well how impossible it is for me to think of establishing myself permanently in a country where I must always live as it were alone and separated by an insurmountable bar from all those who surround me and with whom I should have wished to have made permanent connexions. The national jealousy between England and France seems too much disposed to [increase] that an Englishman permanently settled in France must feel isolated and uncomfortable unless he has in the neighbourhood countrymen of his own to associate with and keep him in countenance.”

(MS/328/5/8)

In addition to the commencement of law studies, when George returned to England, he was also asked to work for both his father and his uncle. The opportunity to live with his uncle was one consolation for George on his return to London.

George’s pursuit of law studies continued a Bentham family tradition established by George’s grandfather, Jeremiah Bentham, after whom his uncle also joined the profession. Already an assistant to his father, Samuel Bentham, George now worked also in the same capacity for his uncle, translating his many works. This however did not make him stop his law studies, which he continued despite his uncle’s disapproval. In a journal entry dated 7th – 24th October 1826 his uncle’s displeasure at his decision to enrol at the Lincoln Inn college in law is made clear:

“I told him I had been entering at Lincoln’s Inn. He said all was very well, although he seemed displeased that I had not brought him my recommendation to sign. However, he was in very good humour with me after dinner till speaking of Blackstone’s Commentaries I observed that book must now become the object of my study. He then asked “what you are not going to study the law for practice” I answered you know that in my circumstances I must earn money “well then if you must earn money by the practice of insincerity and dishonesty, there will be an end of all communication between us. In practicing the law you must learn insincerity and where there is insincerity with me, there can be no sympathy and without sympathy there is no use in coming together so we had better separate than quarrel”. I then said I have no money of my own as long as my father lives I am comfortable but after that I have nothing to depend upon and though I do not wish to hoard or accumulate money yet I must live, upon which he said over and over again that he had given up everything for the public good and he did not see why I should not [do] that as to mere living what should come from him would be much more than enough for that...”

(MS/328/6/4)

His uncle’s hatred of lawyers is clearly expressed in another journal entry dated 28th March – 16th April 1827, where Jeremy Bentham is quoted as saying:

"I would rather see you a tailor, a butcher or a Jack Ketch [executioner], than an indiscriminate defender of right and wrong."

(MS/328/6/11)

George’s decision to pursue law studies evidently put a strain on his relationship with his uncle, wherein other cracks started to appear. During the last years of his uncle’s life, George doubted if he would inherit anything of Jeremy Bentham’s estate, such was the extent to which the relationship between the two men had soured. George continued to study law, despite his uncle’s urging him to renounce law studies in order to concentrate on botany. The law studies were initially seen as a way in which George would be able to work as a full-time assistant to his uncle. However, Jeremy Bentham’s attitude had by now hardened to the point where George was forced into having a difficult choice to make. This he discusses in a journal entry from August 1827:

“For some time I have been no longer a regular at L. I. [Lincoln’s Inn], and (with his comment & approval) had been as you know studying the law at Lincoln’s Inn. This he did not much like though whenever I spoke to him he approved of it, for two or three times, past that I had dined with him, he had been rather pettish yet I thought that nothing more would come. However on Saturday night he suddenly announced that I must give up everything and come every morning to work at his Procedure Code. Unprepared as I was for any such request and feeling the importance of persisting in the course of legal studies I had commenced, I at once objected to this, hereupon he told me that if I refused to do it, he must immediately come to a complete rupture with the whole of our family.”

(MS/328/6/13)

After discussing the matter with his father and John Herbert Koe, his professor in law, George decided to give in to his uncle’s demands and continue to help with his uncle’s work. Keeping his uncle placated was essential for George to keep his share of the family inheritance but this was not without bitterness.

In addition, George was also expected to be present at his house for twice weekly dinners. These meals with his uncle used to greatly displease George, owing partly to Jeremy’s whims, but also due to the presence of one of the regular attendants who in George’s eyes represented a real threat. John Bowring was a secretary at the Greek Committee, created in March 1823 to raise funds in support of Greek independence from the Ottomans. As England’s stance regarding the war was neutral, however, the formation of a fund supporting either side was considered illegal. In 1826, the speculative bubble burst and revealed the bonds to now be worth no more than a quarter of their original discounted value. It seems that the members of the committee had been dipping their fingers into the finances and taking advantage of the donations they received.

Bowring was one of the main actors in the committee, an editor at the Westminster Review and was also entrusted by Jeremy Bentham to oversee an edition of his Collected Works. A firm bond had developed between the two men, which the succession of scandals in which Bowring was engulfed did little to shake. Bowring’s attempts at self-justification in public responses issued through the Westminster Review could not extricate him from the grip of scandal or salvage his reputation in the court of public opinion. Despite this, Bentham denied all accusations against his friend, defending Bowring until the end, and insisting on inviting him to dinner every week, which was not a situation that sat comfortably with George. In a journal entry, dated 17th December 1826 – 16th January 1827, he wrote:

“I am very sorry Bowring gets off so easily. It was in hope it might be a matter of quarrel between him and my uncle, and if once they do quarrel, my uncle will believe the Greek business and other knaveries of his present favourite. I was in hope of another affair about the papers sent to Guatemala (or rather not sent for Bowring has them still and persuades my uncle that they are gone) but this I fear will now blow over.”

(MS/328/6/7)

Afraid that his uncle was being led into a financial trap, George kept a close eye on Bowring. Over time, Bowring’s affairs became increasingly an object of concern for George, as his uncle’s fortune seemed to be getting continually funnelled into Bowring’s losing speculations. More and more, George believed it essential to keep up his legal studies, in order to have a future source of income upon which to fall back. At the same time, he had to keep these studies a secret from his uncle, and to do whatever he could to salvage his relationship with his uncle, to prevent his name from being completely erased from Jeremy Bentham’s will.

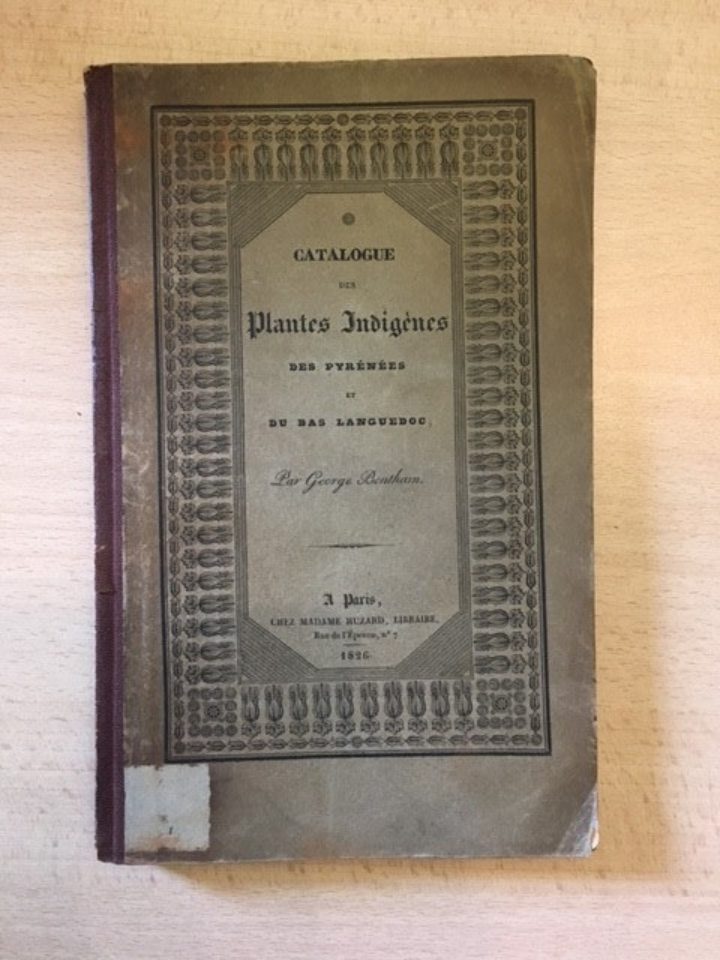

The Linnean Society Library's copy of Bentham's Catalogue des Plantes Indigenes des Pyrenees, published in 1826.

Having been forced to continue his law studies in more secrecy than before, George was able to devote more of his time under observation to focus on his botanical studies.

While George took what he would have regarded as a leisurely approach to botany, this did not mean that his work in this discipline had gone unnoticed. His many encounters with famous botanists are often described in his journals. His first work of botany, inspired by his years of travel in the French countryside was published in 1826 as the Catalogue des Plantes Indigenes des Pyrenees. In a journal entry dated 24th October to 19th November 1826 he writes:

“I spent Sunday in looking about me, dispatching the English girls, finding out my bookseller, etc.. It was on Monday morning that I gave my catalogue to Mme Huzard’s printer. I had all the proofs of the catalogue post by the Saturday night and without anything like the number of faults I might have expected. The preface and accounts of my journey, I wrote chiefly during my weeks of stay at Paris, which I assure you was hard work considering I had a great deal of going about the town for commissions, besides the time I spent looking over some of the principal herbaria...”

(MS/328/6/5)

Also in 1826, he became a Fellow of the Linnean Society, on the strength of his account of his travels in France and the botanical research he had made along the way. This newfound recognition of his talents allowed him to meet and enter into correspondences and exchanges with eminent London botanists.

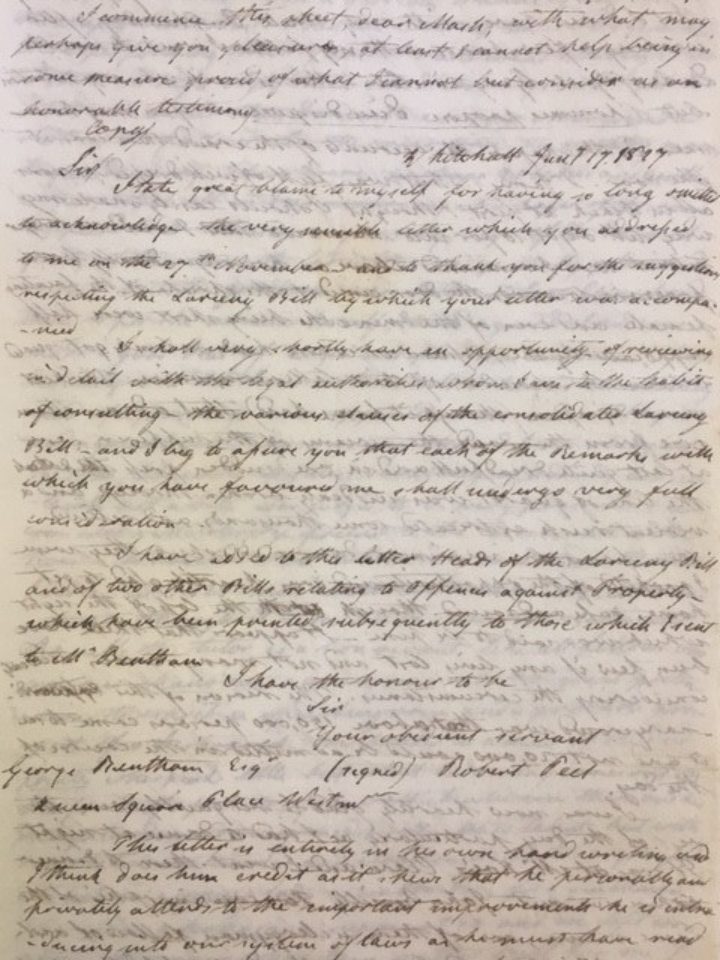

In a journal entry dated 20th January 1827, George was delighted to receive a letter from Professor Robert Peel, and he records his own reply:

“Sir, I take great blame to myself for having so long omitted to acknowledge the very sensible letter which you addressed to me on the 27th November and to thank you for the suggestion respecting the Larceny Bill by which your letter was accompanied.

I shall very shortly have an opportunity of reviewing in detail with the legal authorities, whom I am in the habit of consulting the various clauses of the consolidated Larceny Bill – and I beg to assure that each of the Remarks with which you have favoured me shall undergo very full consideration”.

(MS/328/6/8)

In addition to his work for both his father and his uncle, and his studies and duties at the Linnean Society, George also decided to join the Horticultural Society, for which he became secretary in 1829. In Bentham’s unpublished autobiography, the manuscript for which is held in the archive at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, it is clear how many demands there were on his time:

“Alphonse de Candolle arrived on the 22nd of April, and Kunth, sent by the Berlin Museum, on the 29th and I spent all the time I could spare with them in Frith Street, helping in the sorting the families they had respectively undertaken, took them both to the Linnean Society club dinners and meetings, and to the anniversary dinner on the 24th; with them also to one of Lambert’s overcrowded dinners. At this anniversary I was, for the first time, elected into the Linnean Council, and very regularly attended its meetings; also at this time I joined the Zoological Society, in the course of formation. The greater part of my time was, however, taken up with the Horticultural Society’s affairs.”

George Bentham autobiography, 1800-1834, p. 332

Amid so much activity, and alongside his curiosity and enthusiastic attitude towards botany, George’s doubts about the path he has chosen in relation to his uncle and with regard to his legal studies were brought into sharp relief and were borne out in his writings in his autobiography:

“The year 1830 proved, in some measure, the turning point which determined the future course of my life. The struggles between law and botany fairly began, and although for a time the former maintained its importance in my mind as that on which I was to rely for future support, yet the latter was gradually gaining ground, though it was still some years before it obtained complete mastery.”

George Bentham autobiography, 1800-1834, p. 326

In 1831, George’s father, Samuel Bentham, died. His uncle, Jeremy, passed away just one year later in 1832. After Jeremy Bentham’s death, George inherited his house in London, wherein he would continue to reside for several years.

George was now able to practise as a lawyer, having been called to the Bar in 1831. He attended only once, however. His decision to dedicate himself exclusively to botany came two years later, at the start of 1833, after his marriage to Sarah Brydges, the daughter of a former diplomat, Sir Harford Jones Brydges. In his autobiography, which he had originally started for his wife’s amusement, he writes:

“The year 1833 finally settled the course of my future life. I married, and after some months, finding that there was little likelihood of our having any family, and that my wife’s wishes were very moderate, that our income was sufficient to enable us to live comfortably, though not luxuriously, and that I need not toil for our support, I determined to give up law, to devote myself entirely to botany.”

George Bentham autobiography, 1800-1834, p. 415

The pressure of having an income in prospect of raising a family was no longer a concern for George, and so he no longer needed to focus on law. Not only that, the money he had inherited from his father and uncle would be enough to sustain him and his wife. For the first time in his life, George was able to devote his whole being to the study of botany. For almost thirty years, George Bentham would undertake the ambitious task of classifying all seed plants, having determined that the contemporary classification was inadequate. This research would amount to the work known as the third volume Genera Plantarium, started by Carl Linnaeus, the motive force and figurehead of the Linnean Society.

Antoine Darmon

This blog was published on 22nd September to coincide with George Bentham's 222nd birthday. The letters referenced in this blog are scheduled to be uploaded onto the online archives catalogue in the coming months.

Unless otherwise indicated, all images © the Linnean Society of London, 2022

GeorgeBentham.jpg [Photograph]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GeorgeBentham.jpg Accessed: 22/07/22

Filipiuk, M. (ed.) (1997). George Bentham Autobiography, 1800-1834. Toronto: Toronto University Press

Bentham, G (1826). Catalogue des Plantes Indigenes des Pyrenees. Paris: Huzard. Linnean Society Library copy (Shelfmark: 914.48:582.4 BEN): https://linnlibrarycat.cirqaho...