JA Leach: A Nature Influencer of his Time

JA Leach wrote “An Australian Bird Book”, the first field guide to that continent's avifauna in 1911. But Leach’s bird-guide went far beyond identification. It was a call for deeper love for the natural world.

Published on 2nd September 2022

This essay by Russell McGregor is based on his longer research paper on Leach’s work and legacy.

John Leach had a simple wish: he wanted people to be able to identify the birds around them – or as he put it in an evocative turn of phrase, ‘to name the birds they meet’. But Leach, an ornithologist and teacher, believed that naming birds was merely the first step towards appreciating and understanding them. In doing so, he hoped, bird watchers would also nurture a commitment to conservation.

Leach published the first field guide to Australia’s avifauna, An Australian Bird Book, in 1911, long before the word ‘biodiversity’ was coined. Yet it bears testament to birdwatcher Simon Barnes’ declaration that a field guide is a ‘a hymn to biodiversity’.

As Australia’s first field guide, Leach’s Bird Book initiated a stream of publications encouraging people to observe, identify and appreciate the birdlife around them. That stream, growing into a torrent from the 1970s onward, has rendered Leach’s guide thoroughly out of date. But if we’re prepared to listen, his book can still speak to us today.

Shaping amateur naturalists

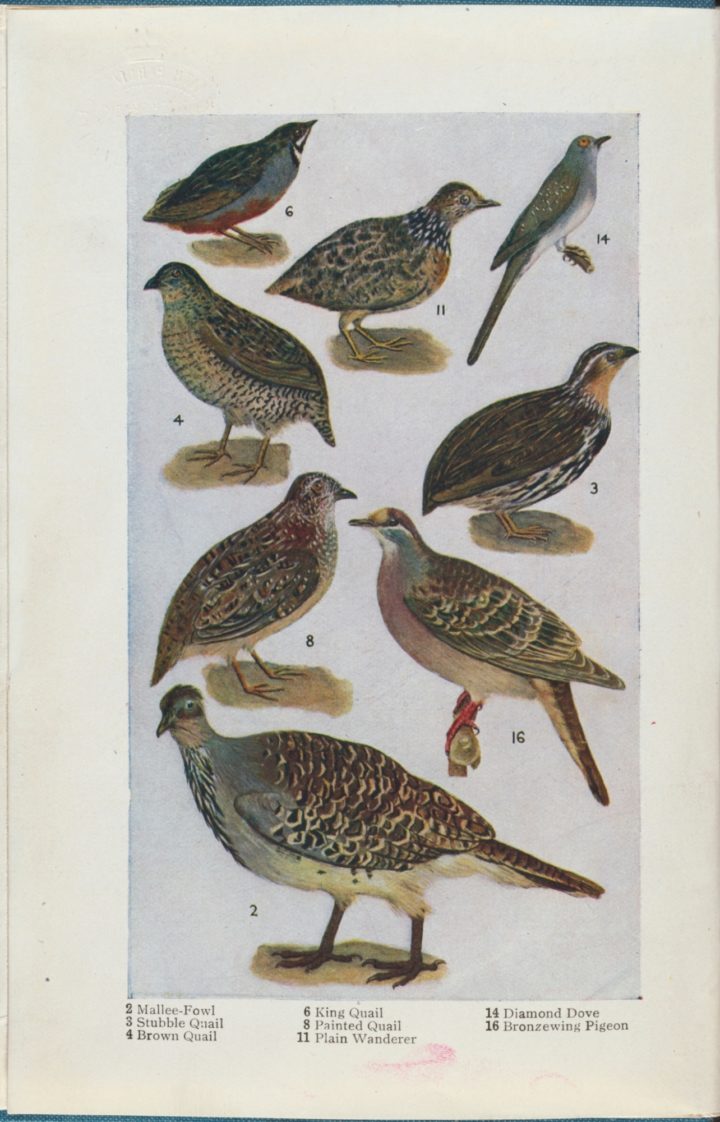

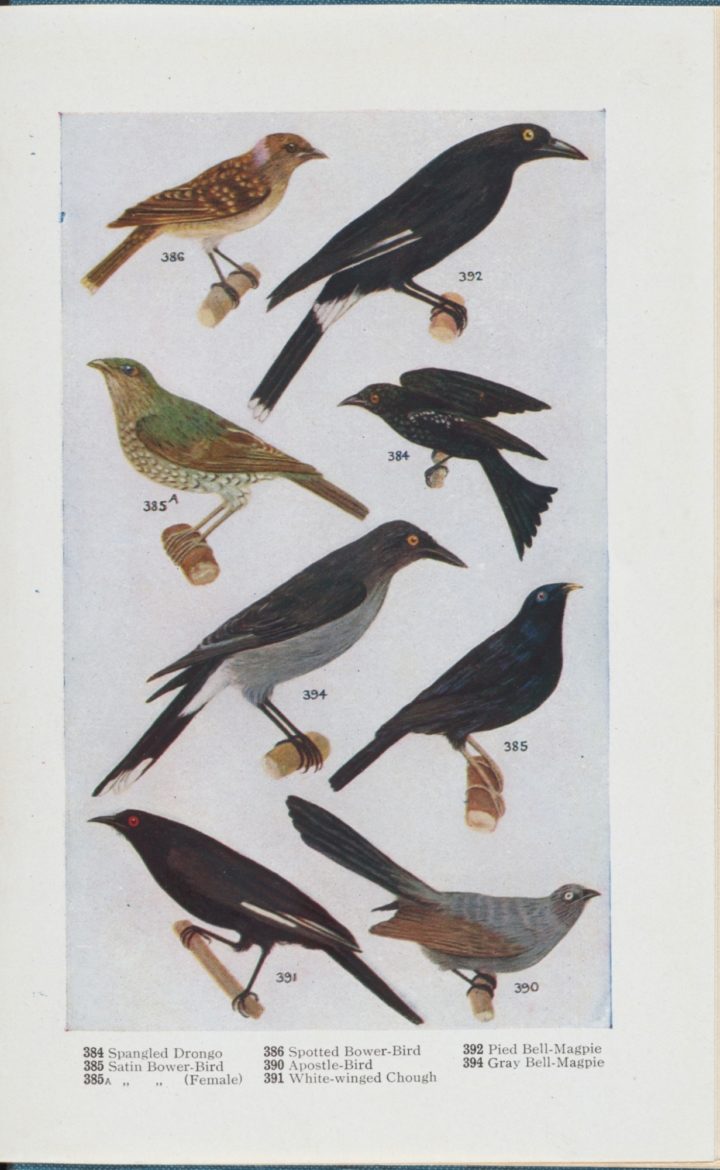

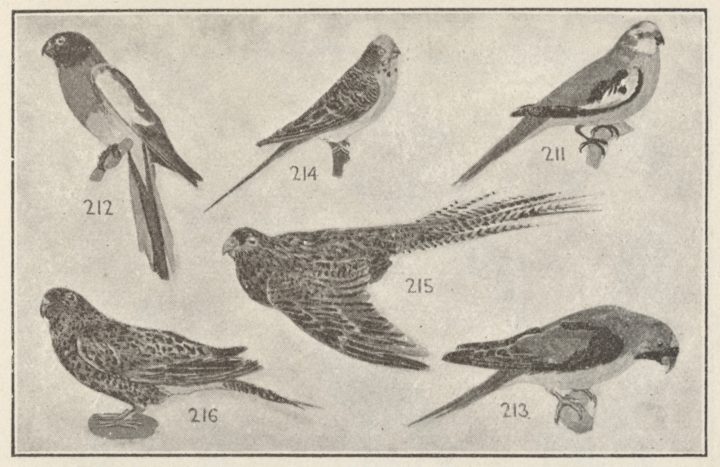

When Leach wrote An Australian Bird Book, the field guide genre was in its infancy, not only in Australia but globally. Guide writers were still struggling to determine how best to combine descriptions with depictions to facilitate identification. Leach was no exception. His identification cues were rudimentary. Most illustrations were monochrome; many were poorly executed. Plumage descriptions were brief, renditions of calls even briefer. Yet Leach’s guide was a milestone in the history of birding in Australia.

Before Leach and his guide, there were keys for identifying Australian birds, but they were not intended for field use and were not particularly useful for identifying live birds. They were meant for birds in the hand, not birds in the bush: for identifying dead specimens rather than fluttering, flighty wild creatures.

Field guides like Leach’s helped drive a crucial shift in birding practice, away from amassing collections of specimens and toward field observation. Beyond that, field guides promoted the pastime of people gaining pleasure from seeing and identifying birds in the wild.

Leach censured the then-common practice of shooting birds as a prequel to identifying them, encouraging instead watching and observing birds for both education and recreation. For him, birdwatching was a species of edifying recreation in the mould of Victorian popular natural history. Accordingly, his Australian Bird Book contained far more than advice on how to match a bird with a name.

More than just a bird: A polymathic approach

While in certain respects resembling its more recent counterparts, Leach’s Bird Book contained features that won’t be found in any modern guide. Most notable in that regard is what Leach called ‘A Lecture’: a continuous passage of prose that ran from the beginning of his field guide to its end, usually placed on the lower half of each page beneath the descriptive notes on identification. Consuming approximately half the book’s page space and more than half its words, the lecture covered a remarkable miscellany of natural history topics.

They included speculations on the configuration of Earth’s continents, discussion of the ideas of Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin, assessments of the size of the mutton-bird harvest on Cape Barren Island, musings on the purpose of the double-storied nest of the Yellow-rumped Thornbill, comparison of the musical talents of British and Australian songbirds, and reflections on the evolutionary significance of coloured wing-patches.

Inclusion of such material in a guide badged as A Pocket Book for Field Use bears witness to birding’s origins in nineteenth-century popular natural history. The retention of this hefty natural history content in all subsequent editions of Leach’s Bird Book, through to the last (ninth) in 1958, testifies to birding’s continuing affinity with that legacy.

Leach realised that a field guide is more than merely an instrument to help pin a name to a bird. It’s a window onto the world of nature, opening our eyes and ears to an avian realm of beauty and wonder. The greatest-ever field guide author, the American Roger Tory Peterson, knew this and offered his guides as means for people to connect with nature and thereby commit to conserving it.

Leach larded his guide with details on avian taxonomy that went far beyond anything that might aid identification in the field. He pressed the point that Australia’s avifauna was of exceptional evolutionary significance. Most of all, his lecture pleaded for conservation. Like much early twentieth-century conservation, Leach’s had a utilitarian slant, promoting the preservation of birds for their usefulness in destroying insect pests. Yet he also celebrated birds for their intrinsic worth as well as their capacity to stir aesthetic and emotional responses in people. Although he was a scientist renowned for a somewhat stiff ‘academic’ manner, Leach knew that emotion was key to cultivating a commitment to conservation.

To nurture emotional attachments to birds, Leach urged the abandonment of ugly and inappropriate names. ‘We need good descriptive names for our varied and beautiful birds’, he entreated, ‘more children’s and poets’ names, and less of the deadly formal “Yellow-vented Parrakeet,” “Blue-bellied Lorikeet,” and “Warty-faced Honeyeater” for some of the most glorious of the world’s birds’. Beyond that, he tried to foster an appreciation of birds as vital components of the nation’s heritage.

A guide for connection

As Australia’s first field guide, Leach’s Bird Book initiated a stream of publications encouraging people to observe, identify and appreciate the birdlife around them. That stream, growing into a torrent from the 1970s onward, has rendered Leach’s guide thoroughly out of date. But if we’re prepared to listen, his book can still speak to us today.

It can do so because Leach realised that a field guide is more than merely an instrument to help pin a name to a bird. It’s a window onto the world of nature, opening our eyes and ears to an avian realm of beauty and wonder. The greatest-ever field guide author, the American Roger Tory Peterson, knew this and offered his guides as means for people to connect with nature and thereby commit to conserving it.

Leach’s guide preceded Peterson’s by decades; his Australian Bird Book was nowhere near as sophisticated as those of the innovative American. But Leach, too, appreciated that truth about the genre he founded in Australia. He understood birdwatching as a way of connecting with nature and knew that connectedness was best secured through a combination of scientific, aesthetic and emotional elements. His Bird Book encouraged connectedness on all three fronts.

Today’s field guides devote far fewer words to natural history and far more to the intricacies of identification. Their illustrations, layouts, formats and styles of presentation outshine Leach’s at multiple levels of magnitude. Yet, explicitly or implicitly, field guides continue the tradition pioneered by Leach, offering not merely a means of naming birds but also an impetus to love and cherish them.

College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University