From the Archives: 'I’ll let him know his place in nature'

It was on this day, 29 June 1895, that Thomas Henry Huxley, biologist and fierce friend of Charles Darwin, died. To mark the occasion, we're reproducing an article published in our members' magazine, 'PuLSe', by Fellow and volunteer, Alan Brafield.

Published on 29th June 2022

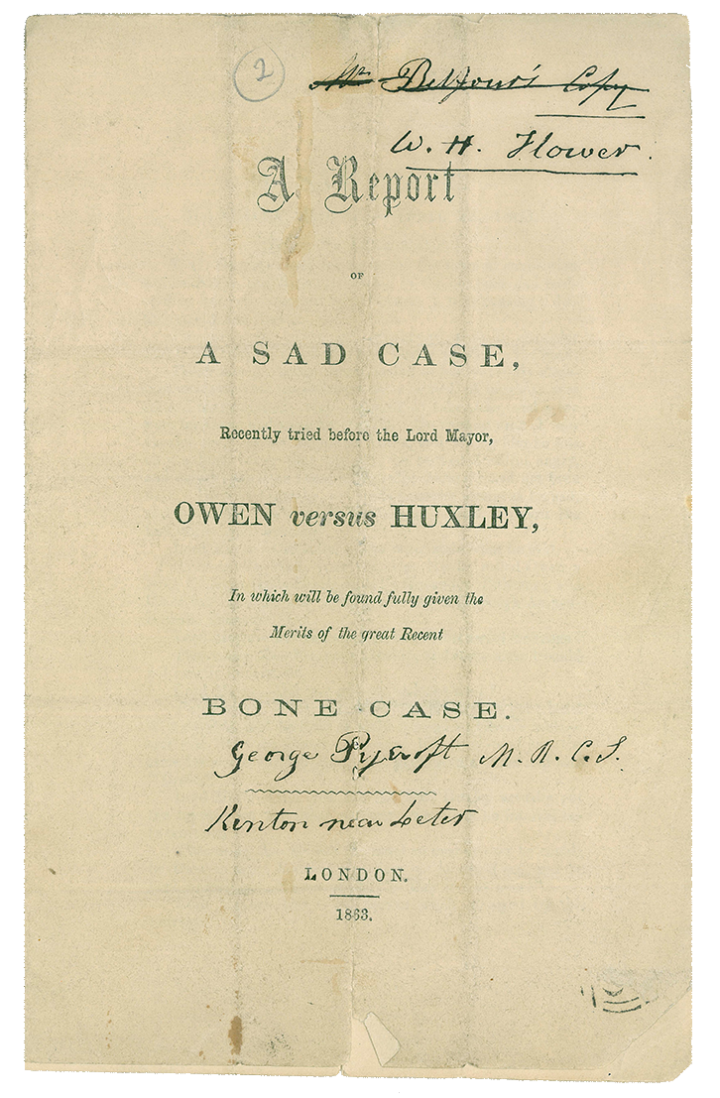

Whilst sorting through some archive materials, Linnean Society volunteer Alan Brafield found a short document dated 1863 entitled ‘A report of a sad case, recently tried before the Lord Mayor, Owen versus Huxley’.

Upon reading the article Alan realised that the document, authored (though published anonymously) by George Pycroft, was a tongue-in-cheek account of a fictional court case between Sir Richard Owen (1804–1892) and Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895). Devised as a short play, the piece was intended to highlight the perceived vulgarity of Owen and Huxley’s very public clashes.

Some background

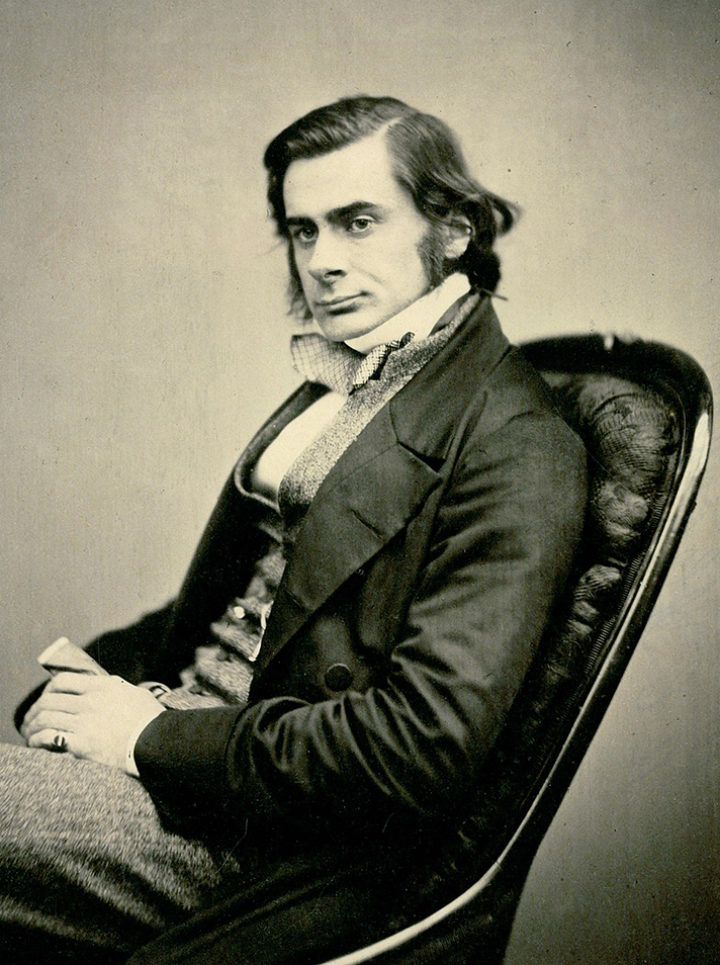

Thomas Henry Huxley (Linnean Society of London)

Sir Richard Owen (Linnean Society of London)

Owen and Huxley clashed continually over their theories, the most famous being Huxley’s debate with Bishop Samuel Wilberforce (1805–1873, who had been coached by Owen) regarding Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection in June 1860, and what became known, in parody form at least, as the Great Hippocampus Question. In 1857, Owen presented a paper to the Linnean Society stating that his anatomical studies of the primate brain showed, in his authoritative view, that humans were separate and distinct from all other primates and mammalia. Though Owen admitted that there were many similarities between man and ape, he supported his theory by asserting that the human brain was the only one to have a hippocampus minor (a ridge in the floor of the posterior horn of the lateral ventricle). Huxley, perhaps now regarded as the superior anatomist, took issue with Owen’s findings and set out to prove him wrong with the results of his own dissections. The following year, with his paper entitled On the Theory of the Vertebrate Skull, Huxley publicly rejected and disproved Owen’s theory with a number of demonstrations (including one by William Henry Flower FLS, 1831–1899), with Owen eventually acknowledging that there was evidence of the hippocampus minor on display in a primate brain.

Old bones, bird skins, offal, and what not

Title page from 'A report of a sad case, recently tried before the Lord Mayor, Owen versus Huxley' (Linnean Society of London)

The Pycroft parody ‘A report of a sad case…’ casts both Owen and Huxley as two crass costermongers (Dick Owen and Tom Huxley) who have been arrested for ‘causing a disturbance in the streets’. The arresting policeman (Policeman X) reports hearing Huxley call Owen ‘a lying Orthognathous Brachycephalic Bimanous Pithecus; and Owen told him he was nothing else but a thorough Archencephalic Primate’. Huxley even sets a live monkey on Owen’s heels, saying ‘’twas his grandfather’. Owen moves to tell the Lord Mayor that he has been attacked, both literally and figuratively, by Huxley’s ‘lower set’ in which he includes one of Huxley’s ‘new pals, Charlie Darwin, the pigeon fancier’. Huxley, in defense, explains: ‘Me and Dick are in the same line—old bones, bird skins, offal, and what not.’ When pressed he states that all was ‘comfortable as long as Dick Owen was top sawyer [and could continue to] throw his dust down in my eyes’. Huxley expands:

…we both cut up monkeys, and I finds something in the brains of ‘em. Hallo! says I, there’s a hippocampus. No, there ain’t, says Owen. Look here, says I. I can’t see it, says he, and he sets to werriting and haggling about it, and goes and tells everybody, as what I finds ain’t there, and what he finds is, and that’s what no tradesman will stand.

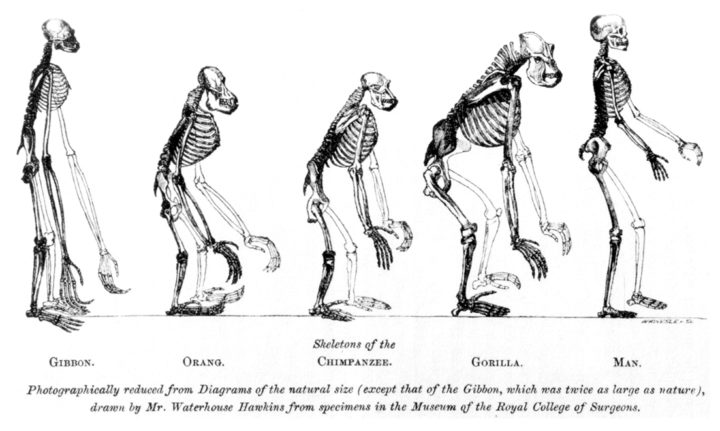

The Lord Mayor decides not to mete out any punishment, except to remind Owen that it would be better to prove his dissimilarity to an ape by acting with ‘gentleness, forbearance and humility’. To Huxley he questions whether he is in search of scientific fact or if he is, in part, simply keen to shame his rival. He asks them to ‘be friends’ and Policeman X asks if ‘Huxley’s monkey was to be restored to him’. And yet, directly after being released from court, both Owen and Huxley end up in yet another altercation, with Huxley vilifying Owen with a sign showing primate skeletons ‘beginning with the gibbon, and ending with man’ and saying ‘I’ll let him know his place in nature’.

Huxley's skeletal comparison of apes and humans from his work Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature (Wikimedia Commons)

A new school of thought

What is interesting to note is that one former owner of this document may have been William Henry Flower himself, a supporter of Huxley and the eventual successor to Richard Owen as Director of the British Museum of Natural History. According to his obituary in the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, Flower re-organised the layout of the Museum, 'rejecting the scheme of Owen', creating the 'ideal Index-Collection' which became the 'prototype of other collections of like order'.

This article was first published in PuLSe, issue 11, August 2011.

Other images

Banner image: 'The Lion of the Season' published by Punch, 18 May 1861. (Wikimedia Commons)

Thumbnail image: Sir Richard Owen. Wood engraving by L. Sambourne, ca. 1884, after Sir E. Landseer. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark