The Linnaean Shell Collection

What happens to a treasure when it isn’t treated as a treasure? Digital Assets Manager Andrea Deneau looks at the history of Linnaeus' shell collection.

Published on 26th April 2022

The Linnean Society houses the specimen collections of Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778). These collections all hold type specimens – that is, the specimen to which the scientific name of a species is attached. All of these specimen collections as well as the individual type specimens could be viewed as treasures in their own right. But, what happens when a treasure isn’t treated as a treasure? This is what happened to Linnaeus’ invaluable mollusca (shell) collection. For many reasons, for over 200 years, this collection has not been treated as the treasure it is now known to be.

Bulla canaliculata Linnaeus, 1758 (syntype); Current name: Tonna canaliculata (LSL.325, The Linnean Society of London)

The Society’s mollusca collection, which contains dry shell material only, includes 588 lots of specimens and represents around 550 of the more than 800 molluscan species named by Linnaeus. Linnaeus’ interest in shells may have started while attending Lund University, where, in order to get the attention and respect of one of the university’s most eminent professors, Dr Kilian Stobaeus, Linnaeus started attending the professor’s lectures on shells. By 1731, with a visit to Stockholm where he collected a large number of shells, presumably from other collectors, Linnaeus had started his shell collection in earnest. Through his many correspondents, he obtained shells from other collectors, including shells from Cook’s Endeavour voyage. Certainly, most of the shells in his collection were from places Linnaeus had never visited. Nevertheless, Linnaeus’ shell collection may have been the finest collection in Sweden after that of Queen Louisa Ulrica, who is said to have been inspired by Linnaeus, as he ‘awakened her interest in the natural sciences and helped her to catalogue her extensive collection of butterflies, plants, shells and books’ (The Royal Palaces, 2022).

The first threat to the collection came in April of 1766, when a fire across Uppsala forced Linnaeus to move his specimens first to a barn, then to a stone building near his house at Hammarby. The collections were affected by mice, insects, and mould; however, when they were inherited by his son, Carl Linnaeus the Younger (1741-1783) (Linnaeus Fil.), he noted it was the plants that had been considerably damaged. For the five years that Linnaeus Fil. owned the collections, he did what he could to keep them in good condition. He even added to the collections, including shells from Daniel Solander (1733-1785). While Linnaeus Fil. might have thought he was augmenting the collections, he was actually reducing their scientific value. However, it could be argued that, with the best of intentions, Linnaeus Fil. was still treating the shell collection with the respect it deserved.

The real mishandling of the shells began when they, along with Linnaeus’ other scientific collections, were purchased in 1784 by Linnean Society founder Sir James Edward Smith (1759-1828). Smith’s main area of study was botany, and as a result, Linnaeus’ non-botanical collections, including the shells, were generally neglected. It is known that Smith gave away a number of Linnaean shells, including some that would have been very rare at the time. But, it was Smith’s practice of adding material to the shell collection that had little or no relevance to the originals that made the greatest impact on the scientific value of the collection. Linnaeus had a system of keeping type specimens described in his publications in small metal boxes. Those shells whose descriptions had not been published were kept in separate packets, and were often labelled as ‘undescribed’. However, Smith, with clearly little regard for the consequences, mixed his own specimens with the original types in the metal boxes.

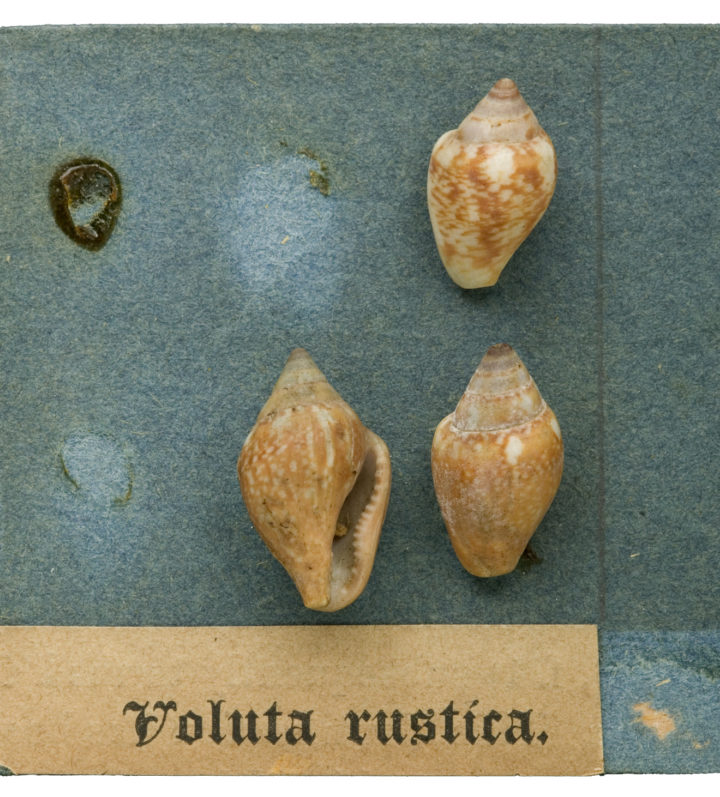

Voluta rustica - an example of Hanley's mounts (LSL.348, The Linnean Society of London)

After Smith’s death, the shells, along with the other specimen collections, were purchased by the Linnean Society in 1829. The shell collection was left in disarray, and made worse through mishandling and poor curation over the following few decades. It wasn’t until the 1840s that the collection underwent its first serious investigation by malacologist Sylvanus Hanley (1819-1899), who attempted to put things in order. Unfortunately, Hanley’s attempt was not completed, and more mishandling and re-ordering occurred under his stewardship. He was also responsible for the shocking decision (by today’s standards) to glue many of the specimens on wooden tablets with blue paper, which can still be seen stuck to many specimens today. Despite his ‘slipshod curatorial work’ (Dance, 1967), Hanley’s resulting Ipsa Linnaei Conchylia (1855) remained ‘the only comprehensive study of the Linnaean molluscs’ (Dance, 1967) until Peter Dance of the British Museum (Natural History) reviewed the collection in the 1960s. Before Dance’s study, the last major attempt to order the shells was done by Henry Dodge in the 1950s. Being in America, Dodge never actually saw the Linnaean shells, and relied almost solely on Hanley’s unreliable Ipsa.

Cypraea flaveola Linnaeus, 1758 with Hanley's blue paper stuck to the specimen (LSL.297, The Linnean Society of London)

Dance’s invaluable study, published in the Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London (1967: 178), remains the most comprehensive study of the Linnaean shells. Dance’s task was an uphill battle, as his description of the state of the shells when he started his study exemplifies:

Those shells which were not lying loose in the drawers were contained in various receptacles, including:

- Linnaean metal boxes;

- blue card trays, traditionally supposed to be Smithian in origin;

- glass-topped boxes of twentieth-century manufacture containing, among others, all the shells glued on wooden tablets by Hanley;

- assorted paper packets, pill-boxes, chip-boxes and similar receptacles, some of which date from Linnaeus’s time.

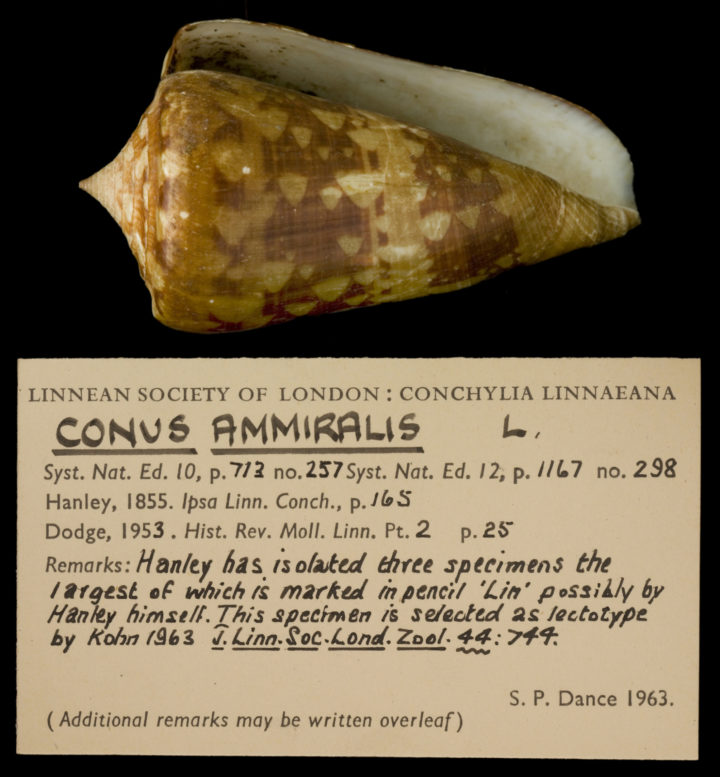

Conus ammiralis Linnaeus, 1758 (lectotype) with a 'Dance label' (LSL.250, The Linnean Society of London)

Dance brought many former identifications into question and highlighted the difficulty of positively determining types in the Linnaean shells. As well as Linnaeus Fil. and Smith’s additions to the collection, and the historically poor-handling and curation of the shells, most of the specimens lack locality data, which must be inferred. In addition, Linnaeus was known to make many descriptions based on other works and illustrations at the time, and it is difficult to establish whether he owned a described specimen before or after he published its description – an important factor in determining type status. There are other factors that complicate the identification of types in the collection, and it is well-worth reading Dance’s full report for the finer details and intricacies.

The Society’s small but globally significant shell collection has both scientific and historical value, and it is incomprehensible how this collection could have been mishandled over the years, even when intentions were at their best. Things have greatly improved though – the Society has had an honorary Curator of Zoology since 1951, and the current Curator of Fish and Shells is the very capable and knowledgeable Oliver Crimmen of the Natural History Museum. Also, the Society was recently honoured to become a project partner with Mollusca Types in Great Britain: A Union Database for the UK. Participation in this project has revealed that almost all of the specimens in the collection have been identified as ‘possible, unverified’ syntypes, lectotypes, or paralectotypes, with only about one-fifth of the shells being verified as type specimens. For all of the reasons discussed above and more, verifying any of the potential types will be very difficult, and in some cases, may even be impossible. Had only this wonderful collection been treated from the beginning as the treasure it truly is.

Andrea Deneau, Digital Assets Manager

Online Collections: All of the Linnaean shells have been digitised along with their typed Dance labels. (https://linnean.access.preservica.com)

Mollusca Types in Great Britain: Participation in this project will allow us to update our shell specimen metadata on our Online Collections to include the current accepted names of the Linnaean specimens. (https://gbmolluscatypes.ac.uk/)

Sources

Dance, S.P., ‘Report on the Linnaean shell collection’, Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London, Vol. 178(1), 1967, pp.1-24, https://academic.oup.com/proceedingslinnean/article/178/1/1/2255065.

Hanley, S.C.T., Ipsa Linnaei Conchylia. The shells of Linnaeus, determined from his manuscripts and collection… Also, an exact reprint of the Vermes Testacea of the ‘Systema Naturae’ and ‘Mantissa’, London, 1855.

The Royal Palaces, Sweden, ‘Highlight: Lovisa Ulrika’s Library’, https://www.kungligaslotten.se/english/articles-movies-360/drottningholm-palace/2019-02-07-highlight-lovisa-ulrikas-library.html [accessed 07/04/2022].

Tunstall, M. to Linnaeus C., Linnaean Correspondence, Vol.15, pp.395-396, 15 June 1772, https://linnean-online.org/777773656 [accessed 11/04/2022].

Way, K., ‘The Linnaean shell collection at Burlington House’, Gardiner, B. and Morris, P. (eds), The Linnean, Special Issue No. 7, 2007, pp.37-46, https://www.linnean.org/our-publications/the-linnean/the-linnean-special-issues.