The embroidery pattern book of Guillaume Toulouze (1656)

Natural history served as a subject for art and crafts for mid-seventeenth century French ladies. Isabelle Charmantier, Head of Collections, finds playful traces of three young French girls in a rare book.

Published on 1st March 2022

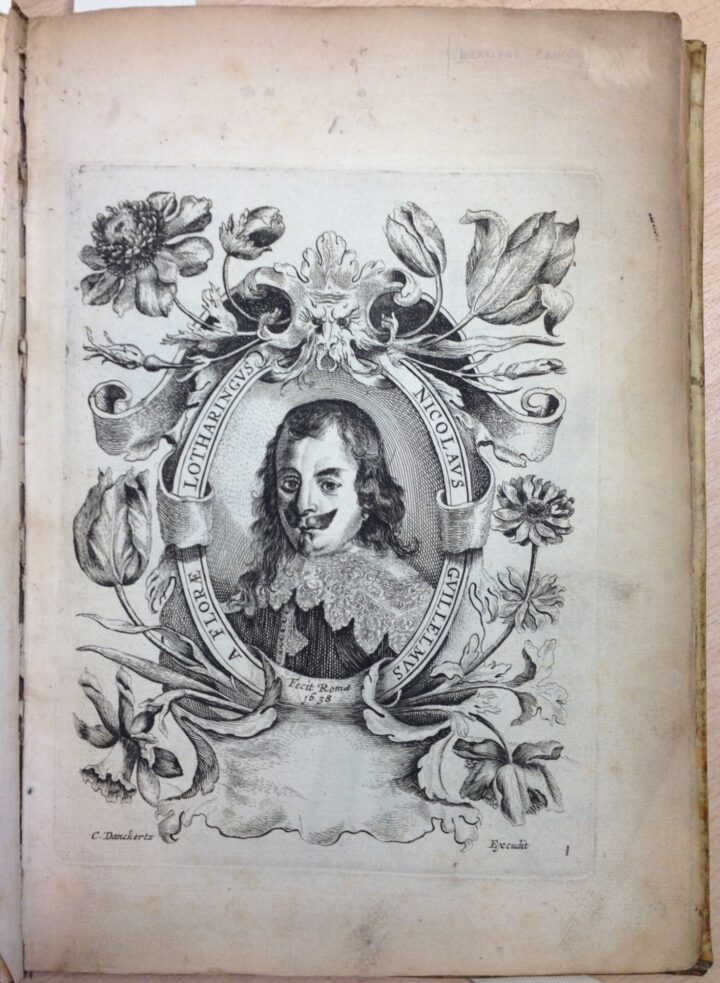

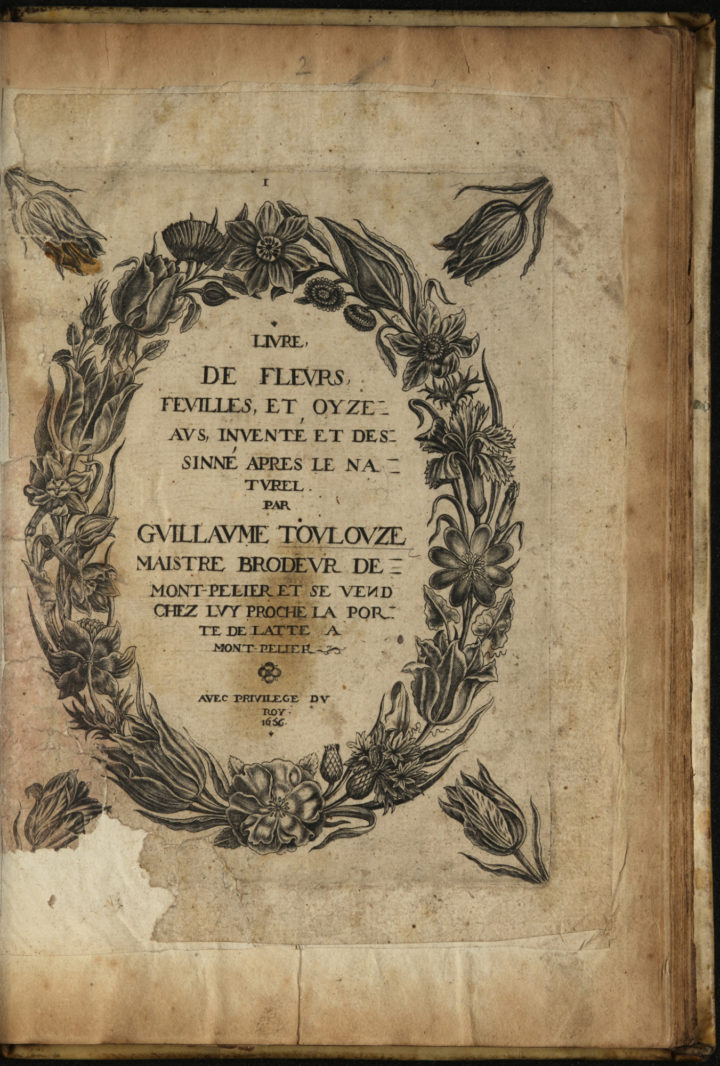

Bound together in parchment within our Rare Books are two rather quaint seventeenth-century books of flowers: Nicolas Guillaume de La Fleur’s Florae Lotharingus (1638) and Guillaume Toulouze, Livre de Fleurs, Feuilles, et oyzeaus, inventé et dessinné apres le naturel (1656).

Title plate of de La Fleur's Florae Lotharingus (1638)

Title plate of Toulouze's Livre de Fleurs... (1656)

Both authors produced prints and etchings. The aptly named de La Fleur (1608-1663) was from Lorraine, and was active in Rome (c.1638/39) and in Paris (c.1644), while Toulouze (fl. 1655) holds a special place for me, as he hailed from my home town of Montpellier, where he was a master embroiderer. As such he produced books to be used as models for embroidery, although the patterns in the Livre de fleurs cater to very experienced embroiderers. It is uncertain when the books were bound together, and it is possible that the binding came later, and that the plates within the two books were initially sold loose.

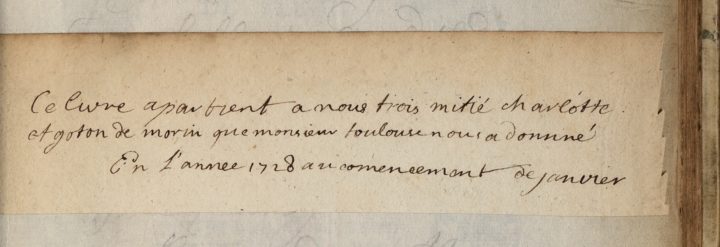

It is probably in this craft and artistic context that the works were given to three young girls, called Mitié, Charlotte and Goton de Morin, as an inserted slip of paper indicates. The slip, written by one of the girls, also reveals that the book was given to them by the author Guillaume Toulouze in January 1728, which seems quite a long time after Toulouze himself is known to have been flourishing as master embroiderer in the 1650s. A quick search for the three sisters on genealogical sites have yielded nothing, and it is unknown whether they were based in Montpellier, and indeed whether Toulouze himself was still a resident of the southern French city by then.

What makes the book a unique and special item are the timeless traces of childhood within it. Colouring, firstly: some flowers, like the carnations and lilies on one plate, or the roses (‘Rosa pallida’) on another, have been partially and skilfully coloured. The eyes of Toulouze's bust, the muse and the putto have all been filled in with a deep, slightly disturbing, black.

Annotations, secondly: the slip of paper states that ‘This book belongs to the three of us, Mitié Charlotte and Goton de Morin, that Monsieur Toulouse gave us. In the Year 1728, at the beginning of January’.

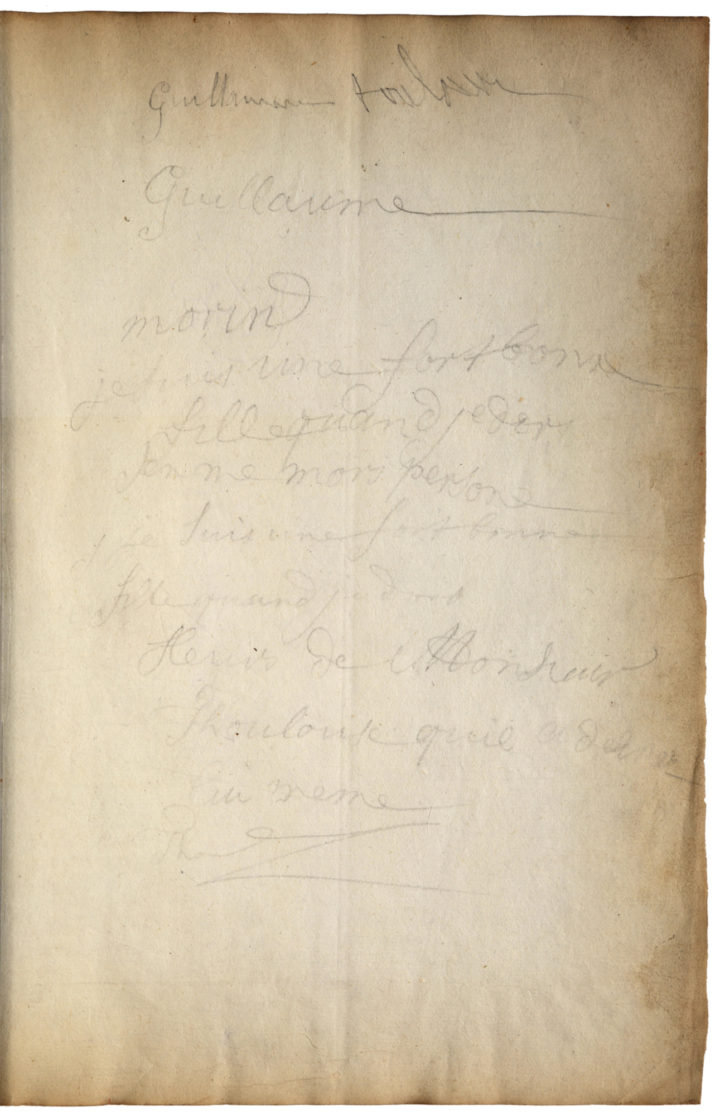

Finally, on the blank sheet immediately following that slip, separating the flowers from the birds, one of the sisters (the youngest?) wrote in pencil amusing and endearing lines, slightly erased by time, and in a very childish hand:

Guillaume Toulouze

Guillaume

Morin

Je suis une fort bonne

Fille quand je dors

Jem [sic] ne mors persone

Je suis une fort bonne

Fille quand je dors

Fleurs de Monsieur

Thoulouse qu'il a donne[?]

Lui meme

While the first three lines seem to be handwriting practice, the rest can be roughly translated as: ‘I am a very good girl when I sleep, I do not bite anyone, I am a very good girl when I sleep. Monsieur Toulouze’s flowers which he gave [to us] himself.’

Beyond the personal history of these three girls, one of whom clearly quite young and learning to write (and not bite!), Toulouze’s book shows the popularity of natural history as a subject for art and crafts for mid-seventeenth century French ladies, whose education would have included painting and embroidery. While a prisoner, and embroidering with Bess of Hardwick, Mary Queen of Scots copied natural history woodcuts from the 16th century naturalists Conrad Gessner and Pierre Belon, as well as natural history themed woodcuts in emblem books, to draw inspiration for her needlework. The Linnean Society has traditionally been a repository for scientific endeavour, but this volume is a nice reminder that knowledge of the natural world trickled down to other sectors of society in many other ways.

Isabelle Charmantier, Head of Collections

References and Acknowledgement

I am very grateful to Marie-Elisabeth Boutroue for sharing her recent paper on botanical art in embroidery books: Marie-Elisabeth Boutroue, ‘Corpus botanique vs. corpus artistique: le cas des livres des brodeurs Pierre Valet et Guillaume Toulouze’, Bulletin du bibliophile, 2020 (2), pp. 381-394.

For Mary Queen of Scot’s use of natural history woodcuts in her embroidery, see Michael Bath, Emblems for a Queen: The Needlework of Mary Queen of Scots (2008) and Margaret Swain, The Needlework of Mary Queen of Scots (1973).