Tabernaemontanus’s 17th-Century Herbal: To Repair, or Not to Repair?

When a 17th-century book starts to decay, do you repair or preserve it? Conservator Janet Ashdown looks at an item from Linnaeus's personal library to explore the solutions.

Published on 21st January 2022

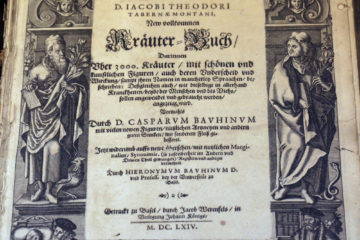

This pleasing German-printed edition of Jacobus Theodorus’s herbal, Neu vollkommen Krauter-Buch (BL.1168), forms part of Carl Linnaeus’s personal library, held by the Linnean Society. Purchased as part of the Linnaean collections by Sir James Edward Smith in 1784, the library was brought from Sweden to London later that same year on board the English brig the Appearance.

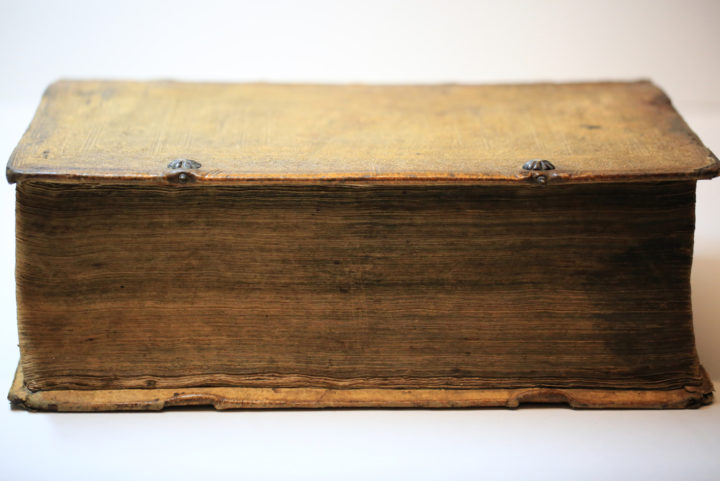

The fore edge of Linnaeus's well-thumbed copy of Neu vollkommen Krauter-Buch

A lifetime’s work

Jacobus Theodorus (c. 1525–90) was born in Germany in what is now referred to as the Rhineland-Palatinate region in the south west. He would become better known by the moniker Tabernaemontanus, a condensed version of the Latinised name of his home town Bergzabern—Tabernae Montanae, or ‘taverns of the mountains’. A physician by profession, he served nobles of the German court before taking on the role of private physician to Philip II, Count of Nassau-Saarbrücken.

Botany was initially more of a hobby for Tabernaemontanus, though he was a student of both Hieronymus Bock and Otto Brunfels. However, after many years of botanising his goal was to produce an herbal. The costly expense of illustrations might have scuppered this if it weren’t for the eventual support of Count Palatine Frederick III and publisher Nikolaus Bassæus. Taking 36 years to complete, volume one of Tabernaemontanus’s Neuw Kreuterbuch was published in 1588, and would become the major work that would cement him as a one of the ‘fathers of German botany’. Many of the illustrations would be reproduced from the works of others like Bock, Leonhart Fuchs, Rembert Dodoens and Pietro Andrea Mattioli. According to Agnes Arber:

This collection of wood blocks became familiar in England a few years later, when they were acquired by the printer John Norton and used to illustrate [John] Gerard’s Herball which appeared in 1597 (Arber 1912).

Tabernaemontanus is remembered in the flowering plant genus Tabernaemontana, named by the French botanist Charles Plumier, which was also used by Linnaeus in relation to his own work on classification.

Loose boards and broken cords

While the Society does have a copy of Neuw Kreuterbuch in its general library (RF.588/591), the work we’re looking at here is more of an updated version from 1664, Neu vollkommen Krauter-Buch, which was ‘verbessert durch Casparum Bauhinum’ (improved by Caspar Bauhin) after Tabernaemontanus’s death. The herbal is a typical example of a 17th-century German binding, with raised cords as sewing supports and bevelled wooden boards, covered in alum-tawed pig skin (a process of tanning skins with alum salts to improve resistance to pollution). The boards are wonderfully blind tooled, a method of decorating leather using heated tools, but without gilding.

The book originally had two metal clasps on the fore-edge to keep it closed, but of these only the bosses (the ornate studs holding the hooks) and hooks remain on the front board; the clasps on the rear board are missing. The front board has separated from the spine, and the hemp sewing supports that would have laced through holes in the board have broken, leaving the cover adrift and the text block in danger of slipping off the cords section by section.

Is it always right to repair?

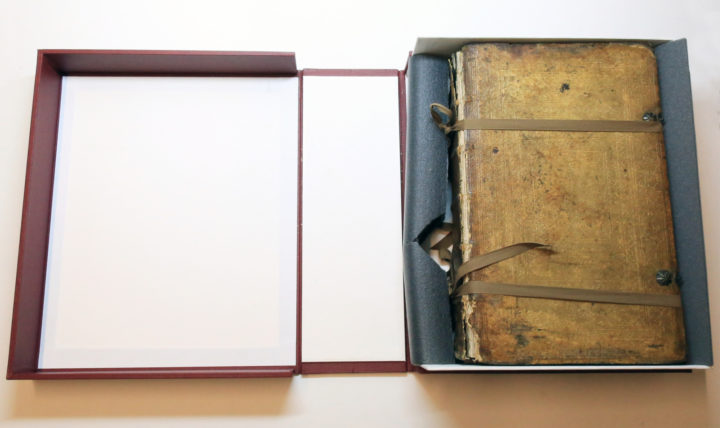

Neu vollkommen Krauter-Buch in bespoke drop-back box © The Linnean Society of London

Currently the book is protected in a drop-back box with the loose board tied in position. Repair and conservation has been considered, but there are good arguments for maintaining the book as is.

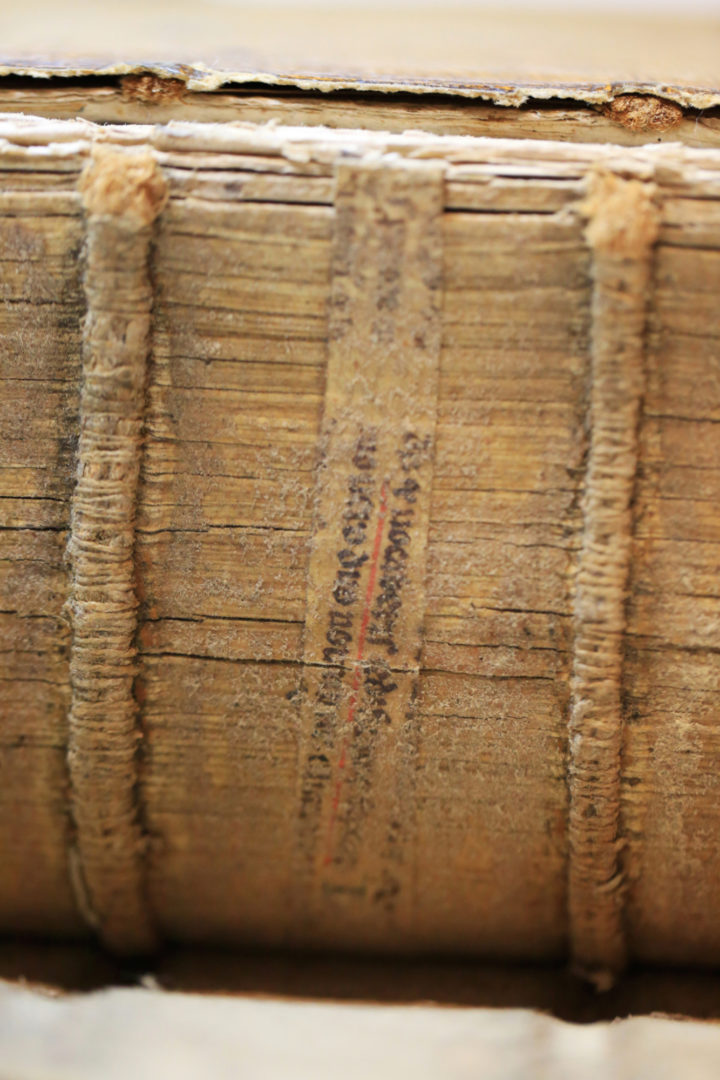

Spine reinforcement made from vellum manuscript © The Linnean Society of London

This work is often looked at within the Society as an accessible example of early binding. In perfect condition, or if repaired, the detail of the sewing method and vellum spine reinforcement (which you can see, is waste cut from a vellum document or manuscript) would be hidden. In its present state, these details helpfully remain visible and allow access to anyone wishing to study book construction, analyse the adhesive or research the pieces of the vellum document used to reinforce the spine.

Often, in the process of conservation and repair, these features would be recorded photographically or with sketches. However a visual record is sometimes ‘not as good as the real thing’. Ensuring that this book is carefully housed and, when in use, is fully protected with book supports and careful handling, will mean that it should remain in its present condition for many years to come. And ultimately, repair will always remain an option if use and conditions change.

Many skills are required by curators and conservators when approaching the conservation and repair of books, but knowing when not to act—when to simply leave something ‘as is’—can also be an incredibly important skill.

Janet Ashdown, Conservator and Leonie Berwick, Special Publications Manager

Reference

Arber, A. 1912. Herbals, their origin and evolution, a chapter in the history of botany, 1470–1670. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.