Opuscula Unbound: Organising our 'Little Works'

Janet Ashdown and Leonie Berwick look into some of the Society's opuscula, discovering a quirk or two along the way.

Published on 29th July 2020

Kangaroo beetle found in a paper in one of the Society's opuscula. © The Linnean Society of London

On the Piccadilly side of the Linnean Society’s library lies a collection of bound offprints, covering a plethora of topics studied in 19th-century natural history, from the tea tree plant, to kangaroo beetles, to termite mounds in Africa. Given to the Society by its Fellows (including Founder James Edward Smith [1759–1828] and botanist Nathaniel Wallich [1786–1854]) and other scientists, the idea was to make sure their scientific papers were readily available for use by their contemporaries. These offprints, known as opuscula (meaning ‘little works’), were bound together, often thematically, but in the Society’s collection those of ‘B. B. Woodward’ look a little different from the rest. Bernard Barham Woodward (1853–1930), a malacologist and Librarian at London’s Natural History Museum, bound his opuscula in the repurposed covers of biblical tracts like Jubilee of the Church, Church Work, and Mission Life. Some even contain notes from the author, or letters about the paper between peers.

The Pitfalls and Plans

Many of the Society's opuscula hold papers of differing size, creating a dirt trap over the years. © The Linnean Society of London

However, there are some pitfalls to these bound volumes. In some cases they have been inappropriately bound, with some being overly bulky. Others bind opuscula of differing page sizes together; often they can be difficult to open flat and can become dirt traps—inevitably of detriment to the item.

Over the past ten years there has been the occasional flood in the building, and the bound opuscula have suffered water damage as a result. Yet, this has offered the opportunity to rethink the way these items have been kept, and make them more easily accessible for research. Conservator Janet Ashdown has been making her way through the most damaged volumes, dis-binding, cleaning, repairing and making them easier to handle. Keeping them as separate ‘pamphlets’ with individual protective paper covers, they are kept in the same order (in line with how they were catalogued) and housed in conservation grade boxes; often researchers may only require one paper, and this would allow library staff to retrieve just the item requested. Additionally, the new binding is completely reversible, so, if at any point in the future they need to be stored differently, the opportunity to do so is available. We look forward to making more discoveries in the future as work continues on this relatively under-utilised collection.

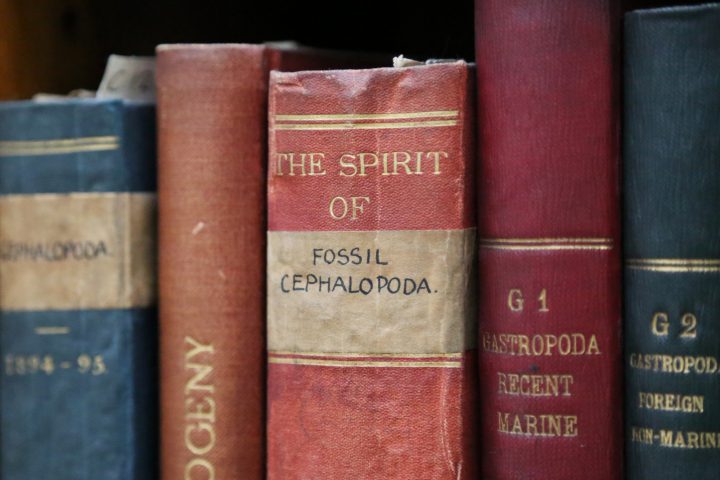

One of the imaginatively repurposed covers in the collections. © The Linnean Society of London

This article was originally published in the July 2020 issue of the Linnean Society's publication PuLSe.